Pramila Devi’s shrouded body lay on a bier, resting on a rock on the banks of a muddy Ganga.

The 36-year-old mother of three had died the previous night in a village in Uttarakhand, a day after testing positive for Covid-19.

Their son Suraj Kumar, 16, watches his mother at their home in Kaljikhal, Uttarakhand Reuters/Danish Siddiqui.

Pramila’s death on Sunday is a sign of how poverty, fear and a lack of facilities are adding to Covid-19 fatalities in remote villages, where many shun tests for fear of testing positive and being forced to go to hospital far from home.

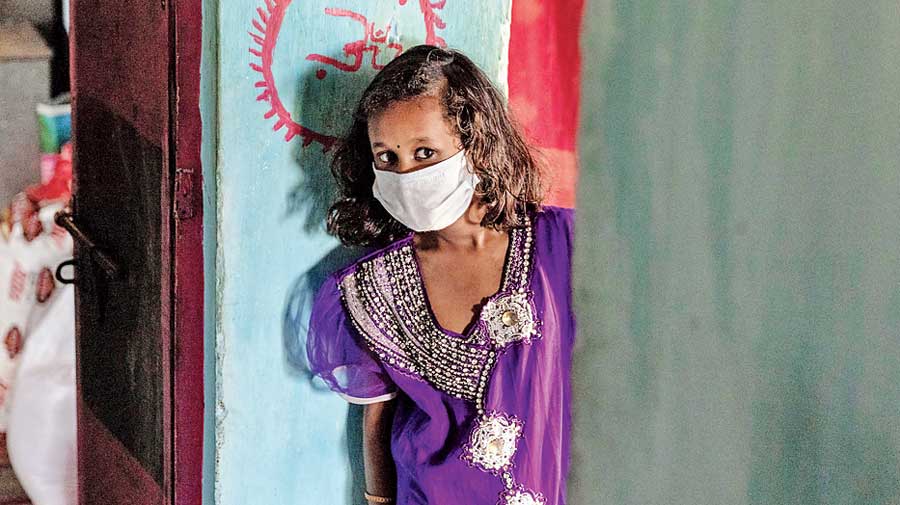

Suraj’s sister Ankita Kumari, 10, looks at their mother. Reuters/Danish Siddiqui

India’s Covid-19 caseload stands at 27.16 million, with 311,388 deaths, central government data from May 26 show. But some experts estimate the numbers are far higher, due in part to low testing rates in India’s hinterlands where Covid-19 cases are spreading rapidly.

Pramila’s eldest daughter got married and moved away in late April after the family hosted a ceremony attended by over two dozen people, her husband Suresh Kumar, 43, told Reuters.

Suresh and his nephew Rajesh Kumar help Pramila to her feet. Reuters/Danish Siddiqui

Two weeks after that, Pramila suffered a bout of diarrhoea. But it was not until 10 days later that Kumar, who has no income and depends on handouts, took her to a nearby dispensary that has been turned into a small Covid-19 facility with four beds.

The dispensary is equipped with one oxygen cylinder and one concentrator, said Aishwary Anand, the only doctor there.

Rajesh carries Pramila to a local government dispensary. Reuters/Danish Siddiqui

Pramila tested positive for Covid-19 with very low blood oxygen levels. Anand advised Kumar to take her to a bigger hospital, but costs were a deterrent.

The couple returned home, where their two other children — a 16-year-old boy and a 10-year-old girl —were waiting.

The journey to the dispensary on the tough terrain before they found a creaky taxi. Reuters/Danish Siddiqui

The next day Pramila’s nephew carried her to a creaky taxi, which returned her to the dispensary. Another patient was using the oxygen cylinder and the oxygen concentrator did not work because of a power outage.

“We need power,” Anand pleaded with an electricity department employee over the phone, as he paced the dispensary wearing white protection gear.

Dr Aishwary Anand treats Pramila at the dispensary. Reuters/Danish Siddiqui

Eventually power was restored, Pramila had access to the concentrator and felt well enough to return home. But when she felt sick again, the family called an ambulance to take her back to the clinic, where she was pronounced dead on arrival.

“I’m yet to inform my eldest daughter of her mother’s death,” a distraught Kumar said, crouched on the banks of the Ganga.

Dr Anand requests an official over the phone to restore power so he can run an oxygen concentrator. Reuters/Danish Siddiqui

Uttarakhand, which shares its borders with China and Nepal, reported 45,568 Covid-19 cases and 6,020 fatalities as of May 25.

Its city of Haridwar recently hosted the weeks-long Kumbh Mela gathering that saw hundreds of thousands of ash-smeared ascetics and devout Hindus jostling to take a dip in the Ganga.

Pramila before her condition improved and she was discharged Reuters/Danish Siddiqui

Some experts fear that the event led to a surge in Covid-19 infections both in the crammed city and other parts of India as devotees returned home.

On the eastern edge of Haridwar, Uttarakhand’s Pauri Garhwal district —where Pramila’s family live — has reported 5,155 Covid-19 cases and 241 deaths. But locals and doctors say many in the district who are suffering Covid-like symptoms refuse to get tested or test too late.

“We’ve launched radio and newspaper campaigns to spread awareness about Covid and encourage testing,” said Manoj Kumar Sharma, the district’s top health official. “But despite our efforts there is some resistance in rural areas to getting tested.”

Pramila feels unwell again. She dies on May 23. Her body is loaded atop an SUV on May 24. Reuters/Danish Siddiqui

Reuters reporters hiked uphill with medics for over an hour to get to Pitha, a village in the district with no road access.

Pramila’s body is taken down for cremation on the banks of the Ganga. Reuters/Danish Siddiqui

There, Jai Prakash, 38, had pleaded with his neighbours to get tested. Despite his appeals, only a dozen of the village’s nearly 60 inhabitants did so.

Pramila is cremated. Reuters/Danish Siddiqui

Only nine among the around 200 residents of the nearby village of Tangroli — declared a Covid-19 containment zone with more than a dozen positive patients — showed up for testing the day a medical team camped outside their village.

“My neighbour did not want to get tested,” said Deepak Singh, who works for a company in New Delhi but returned to his village this month. “He asked me if I was willing to take care of his household expenses if he tested positive.”

Reuters