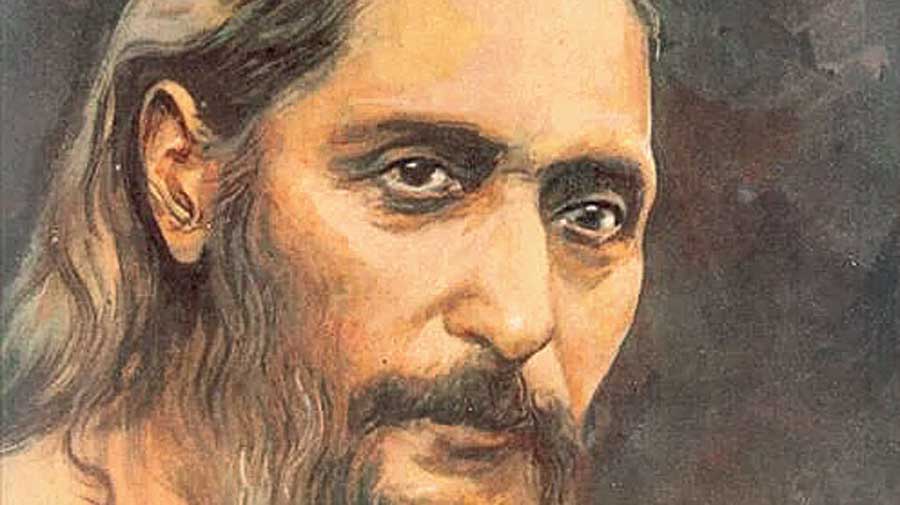

Akhilesh Yadav’s comments on Uttar Pradesh’s handling of the virus contain descriptions of the 1918-1919 ‘Spanish flu’ by the Chhayavad poet, Suryakant Tripathi ‘Nirala’, in his memoir. UP’s former chief minister has shown not just a familiarity with the great poet’s work but an internalization of it that has enabled him to understand the purgatory-like situation we are in and to use that literary allusion to great, explicatory effect. Quoting Nirala, he has pulled our attention to the identicality of the 1918-1919 scene and the horror of countless corpses that have been seen floating on the Ganga along villages in our current torment. And of mass burials along the river’s banks.

Those who have not read or cannot read Nirala’s memoir, Kulli Bhaat, in the Hindi original, have the chance to read its translation into English by Satti Khanna (A Life Misspent, HarperCollins). From the time the virus started last year, different columnists cited the original work and its translation so vivid and powerfully plugged into our agony. But now, with the Ganga becoming the carrier of the virus-dead and its banks their burial site, Nirala’s description acquires a new and macabre ring of reckoning.

When just over 20, Nirala went from Bengal (where he was born — Mahishadal — and was living) to Rae Bareili where his wife was with her parents at that time. He says he saw on his way the Ganga swollen with dead bodies and on reaching his wife’s home learnt that she had died. Others in the family followed: a cousin who had been sent to help out, followed by the cousin’s wife and his daughter. “My family disappeared in the blink of an eye,” he writes. “In whichever direction I turned I saw darkness... ” And he writes about a shortage of wood in the villages to cremate their dead, whence the consigning of the bodies in the waters of the river or their burial on the river’s banks. His wife, Manohara, we learn, was adept in the khari boli, Hindi’s most prevalent form, and had played no small role in kindling his own literary spark. Her going diminished Nirala’s world incalculably, irreparably.

And so, as we speak today of ‘countless bodies’ and ‘corpses’ in generic terms (more so when they belong to ‘rural India’), we must remember that there are Manoharas among them, and persons whose deaths have done something much deeper, sharper and longer-lasting than ‘disposing of the dead’. While the Niralas among the survivors will write about the agonizing experience afterwards, we must for now thank Akhilesh Yadav for connecting us to that inexpressibly tragic and incredibly pertinent experience of the poet.

As the virus lurches into the villages from the stricken cities and towns and from totally and dangerously ill-advised mass congregations such as the Kumbh Mela, we need to hearken to all those who have been warning us about the exactions of neglect — by the authorities and by us, the people, through our callousness.

Is it already too late?

I do not know enough to say that it is, or that it is not. I do not know how many pilgrims to the Kumbh came from and went back to villages across the country but more significantly to villages from which bodies have been let into the river. Those who attended the Markaz Masjid event at Nizamuddin in New Delhi in March 2020 were numerically insignificant compared to those at the Kumbh but reports speak of many attendees there testing positive. I do not know how many of the tenaciously agitating farmers near the national capital have been returning to their villages and coming back to the protest sites in relays. I know of course or can guess like anyone else that the majority of them have not been vaccinated. And I know too, like anyone else, that in West Bengal, the holding of mega rallies was a massive risk taken in the teeth of warnings and pleas for their cancellation.

Experts say the spike should start to slacken by June or July. They have to be right. But I cannot wish away the doubt: if they are basing their prognoses on models that use the data of reported cases alone, would the data of unreported cases, if they were to come in, alter the picture? Or has some sophisticated extrapolation factored in the rural scene? Again, I can only pose the question, not attempt an answer to it. As a lay person, I am just not qualified to do so.

But as one whose memory of Nirala’s observation has just been refreshed, this much I can say: rural India is as yet unmapped in the virus’s cartography. And only two interventions can help rural India, which is the bulk of India, meet the challenge. First, an intensive vaccination programme that covers at least 30 per cent (said to be the appropriate extent) of the rural population by the end of 2021. Second, an intensive awareness initiative that tells village India that wearing masks is not an option but a desideratum (using a simpler word, of course). The first needs vaccines and vaccinators — both in dire deficit. The second needs community leaders to spread the word, not government or Opposition leaders although they are welcome to join, if they can find the time. But where are the community leaders?

Did anyone of note from among our godmen and godwomen, our sadhus and sadhvis, say a word about the risks of attending the Kumbh? Some might have; I missed them. So did the 10 million who attended. But who will ever know how many of them today rue the day they dipped into the Ganga virtually stuck to each other in these days of ‘social distancing’?

Where are the community leaders, I have just asked. The answer is: everywhere. The problem is they have muted themselves. They need to un-mute. They need to shout out the message. If one of them says, ‘Chalo, Kumbh’, millions up and start. If one of them says, ‘Ruko, mat jao, desh ko bachao’, will they not listen?

All faith traditions and communities in India — Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Jaina, Sikh — place trust in community leaders above other kind of leaders. Those community leaders must find their voices and raise them today to save India.

Nirala said about 1918-1919 that whichever way he turned, he was in darkness.

India, seventy and more years after swaraj, has to be different from the India which Lord Chelmsford ruled from Delhi or Sir Harcourt Butler from Lucknow. It cannot by plain default or mismanagement let the Ganga, if it has a mind of its own, say it is not.