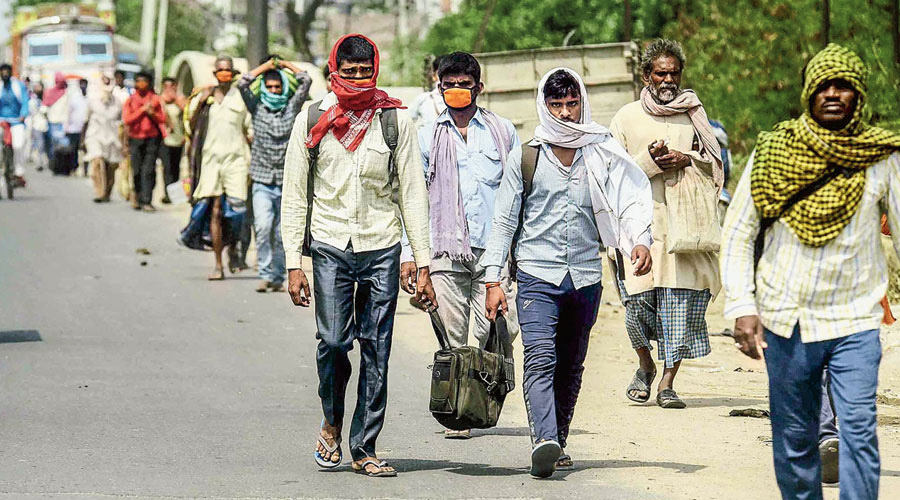

Migrant labourer Raja Kumar’s lockdown-induced miseries in successive years may have been less acute if the country’s governments had not sat on a 42-year-old legal provision that the Centre is now set to implement under a Supreme Court nod.

Kumar, 25, who worked in Noida for a paltry Rs 225 a day, had to return home to Sameswari village in Bihar’s Banka district in April when work became unavailable amid the second wave of Covid. But the labour contractor who engages him did not give him a transport allowance.

“I had to borrow money to go home,” Kumar said.

Had the government implemented the Inter-State Migrant Workmen Act, 1979, Kumar would have been able to register himself as a migrant labourer in his home state and in any state where he chose to work and claimed social security.

Registration under the act would have ensured his protection under the labour laws relating to minimum wage, safety and accident coverage. His labour contractor would have had to pay him a transport allowance for the journey back home.

An additional benefit of the registration would be that during crises like the pandemic, state governments looking to provide free rations or meals and other help to stranded migrants would be easily able to identify and reach them all.

After the Covid outbreak last year, an out-of-work Kumar had been forced to stay back in Mumbai — where he worked then — running up debts to feed himself.

Unorganised-sector workers like Kumar may now hope for easy registration and government welfare, thanks to a June 29 directive from the Supreme Court.

The apex court — which had taken up the matter on its own — criticised the delay over the database and directed the labour ministry to finalise and implement the portal by the end of July.

(The 1979 act has now been subsumed under a new labour law, the Code on Occupational Safety, passed by Parliament last year.)

On July 19, the Centre told Parliament that an Aadhaar-seeded National Database for Unorganised Workers would become operational from August.

To a question from Congress member Suresh Kudikonnil, labour minister Bhupender Yadav said his ministry was developing a portal for the database in collaboration with the National Informatics Centre. A dry run and a security audit were under way.

“The project is expected to commence the registration work by August 2021 after addressing all critical technical issues. Thereafter, the state governments are to populate the data on the portal through mobilising the unorganised workers,” Yadav said in a written reply.

Workers will be able to register themselves free of cost at nearly 4 lakh “common service centres” and select post offices, Yadav said.

The apex court has also directed the enrolment of more beneficiaries under the National Food Security Act, which provides for up to 75 per cent of rural people and 50 per cent urban residents to be brought under the subsidised food programme.

With the rural-urban population ratio being 70:30, about 67-68 per cent of Indians should be covered under the programme. But the government’s list of beneficiaries, based on the National Statistical Office’s household consumption survey report for 2011-12, covered barely 60 per cent of the population. The apex court has directed a list revision.

A survey of 8,023 migrant labourers by the civil society group Stranded Workers Action Network (Swan) between April 21 and May 31 showed that about 82 per cent of these workers had at best two days’ worth of rations left. Seventy-six per cent had Rs 200 or less left with them.

“I feel the government should increase our wages and provide subsidised rations at the workplace as well as medical insurance,” Kumar said.