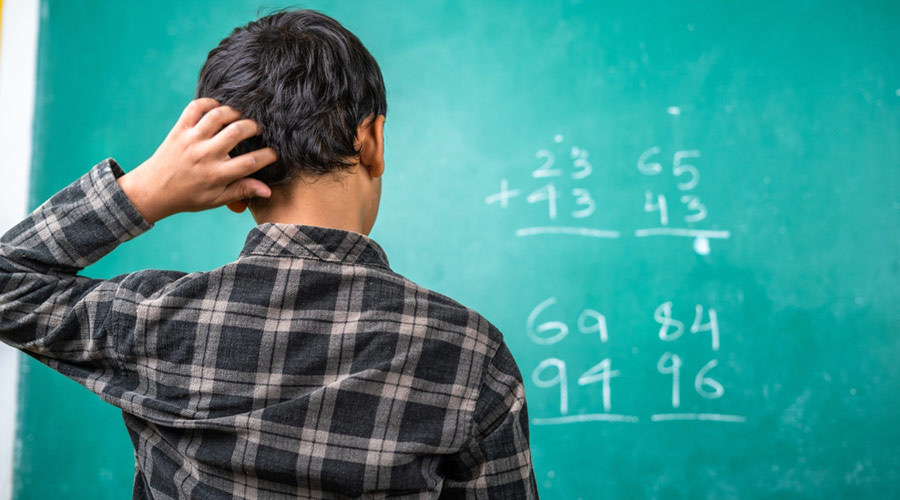

There’s some good news but mostly bad news in a new report on rural education. More children, and particularly girls, are enrolled than ever before in schools around the country. But many in the higher classes are still unable to read short sentences prescribed for Class II children and do elementary division, according to the Aser report for 2022, done at a national level after a four-year pandemic gap.

Unsurprisingly, the two brutal Covid-19 years have hit children’s studies badly. At a national level, basic reading abilities have fallen back to where they were before 2012. Less badly affected are basic arithmetic levels which are back to where they were in 2018. “India had one of the longest durations of school closures” worldwide and “clearly the pandemic has resulted in learning loss,” says Aser Centre director Wilima Wadhwa.

The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) is conducted by the Pratham Educational Foundation of rural households and is usually done annually. This year it reached out to almost 700,000 children in 19,000 villages across 616 districts.

How bad are we talking? The percentage of Standard III children who can read a Standard II text fell from an already miserable 27.3 per cent in 2018 to 20.5 per cent in 2022. Similarly Standard V children who can read a Standard II text has dropped steeply from 50.5 per cent in 2018 to 42.8 per cent. Here, the figures vary from one state to another but reading abilities fell by more than 15 per cent in three states – Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat and Himachal Pradesh – and by 10 per cent in five states – Uttarakhand, Rajasthan, Haryana, Karnataka and Maharashtra.

'Catch up' interventions needed

There’s a very slightly brighter picture by the time students reach Standard VIII – by this time 69.6 per cent of children can read a basic text but that’s down from 73 per cent in 2018. However, that also means that more than 30 per cent of Class VIII schoolchildren cannot read a Class II text. “By the time children reach Grade VII, they have already spent half a dozen years in school but have skills that should have been acquired in 2- 3 years,” says Pratham Education Foundation chief executive Rukmini Banerji. “Anger at and feelings of betrayal by the education system are not uncommon among youth. “Catch up” interventions are urgently needed,” she says.

When it comes to basic mathematics, however, the picture is also gloomy though the percentages are looking better but only very slightly. In 2018, 44.1 per cent of Standard VIII children could do Standard II division and that has risen slightly to 44.7 in 2022. This obviously means over 50 per cent can’t do basic division but there are grounds for cheer. The report says: “This increase has been driven by improved outcomes among girls as well as among children enrolled in government schools, whereas boys and children enrolled in private schools show a decline over 2018 levels.”

Move away from private schools

One of the major findings of the report is that parents have, over the last four years, moved to put their children in government schools and shifted away from the many private schools that have sprung up in recent years.

“In practically all states and for all age groups, there has been a significant shift in enrollment away from private schools into government schools. For the country as a whole (in rural India), the percentage of all children aged 11 to 14 who are enrolled in government schools has risen from 65 per cent in 2018 to 71.7 per cent in 2022,” notes Banerji.

There’s some positive news on school enrolment in higher classes. According to government census data, in 2011, there were 13 million students enrolled in Class VIII and in 2020, there were 22 million. The data suggests that “not only are almost all children in India enrolling in school but they are also staying enrolled for the full elementary school cycle,” says Banerji.

Enrollment of girls up sharply

The brightest part of the national educational sector is that the number of girls attending school is up sharply at all levels. In 2006, 10.3 per cent of girls between the ages of 11-14 were out of school. But girls’ education is picking up. In 2018, 4.1 per cent of girls between 11 and 13 were not in school. In 2022, more girls than ever are going to school regularly and just 2 per cent are not enrolled anywhere. Only in Uttar Pradesh are 4 per cent of girls still out of school.

Even in the 15-16 age group, the picture has improved with only 7.9 per cent of girls not attending school compared to 13.5 per cent in 2018 and over 20 per cent in 2008. Only in three states do these promising figures collapse with 17 per cent of girls in this age group out of school in Madhya Pradesh, 15 per cent in Uttar Pradesh and 11.2 in Chhattisgarh.

Covid-19 had a devastating impact on education across the country and the shift to government schools appears to be one result of this. Parents who were financially hit by the pandemic or worried about a drop in income are thought to have moved their children to government schools which are completely free till the higher classes. It’s also thought that some private schools were unable to pay salaries and make ends meet and therefore closed down during Covid-19.

30% children opting for private tuition

Even parents who did take their children out of private schools did in many cases rustle up cash to make up for any learning deficiencies by organising private tuition on a bigger scale than ever before. Nationally, 30.5 per cent of children are now doing regular out-of-school tuition up from 26.4 per cent in 2018.

One government success in education is creating pre-school centres along with anganwadi centres (AWCs) around the country. Across rural India 78.3 per cent of 3-5-year-old-children are now enrolled in some form of early childhood education. Out of this number, 66.8 are now enrolled with AWCs compared with 57.1 per cent in 2018. “The fraction of children in this age group not enrolled anywhere has fallen sharply,” says ASER research director Suman Bhattacharjea.