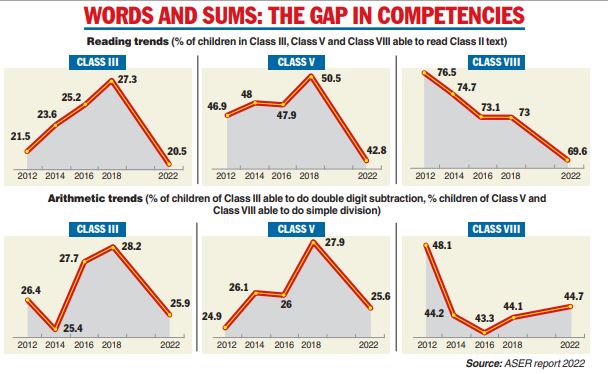

Reading competency had declined more than arithmetic skills among school children during the pandemic period, a survey of learning standards of children between 3 and 16 has found.

Some educationists said children had got hooked to computers and mobile phones during the Covid years, which might have affected their reading habits.

The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2022, brought out by the NGO Pratham, found that 20.5 per cent children of Class III could read Class II-level text in 2022, against 27.3 per cent in 2018.

Reading competency has fallen among students of Class V and VIII too. Their performance in arithmetic has also declined, but not to the extent that reading skills have.

Among states, Kerala — which often scores high on education markers — Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana have registered a decline in reading competency by more than 10 percentage points among Class III students between 2018 and 2022.

The deterioration in Class V is more than 10 percentage points in Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Rajasthan, Haryana, Karnataka and Maharashtra.

The ASER survey was held to assess the school performance of children in the 3-to16-year age group and their ability to do basic reading and arithmetic tasks. A total of 6,99,579 children from 3,73,554 households in 616 districts took part.

Shankar Maruwada, chief executive officer of EKStep, an NGO working in the field of school education, said children’s association with computers and cellphones had increased during the pandemic.

“If the children are hooked to screens for longer durations, their habit of reading printed matter may suffer. This might have affected the reading skills of the students. But it needs to be investigated,” Maruwada said.

Rukmini Banerji, CEO of Pratham Education Foundation, told The Telegraph that children continued to tap into their arithmetic skills, be it while purchasing items or playing games, while reading was a standalone activity.

“The report shows there is a decline in learning levels. But the decline has been checked by the support the students got in learning. The parents and the community have helped children. Such help should be promoted,” Banerji said.

The Right To Education Act provides for free and compulsory education for children between 6 and 14.

The survey found that the school enrolment rate among children in this age group has increased from 97.2 percent in 2018 to 98.4 per cent in 2022.

Admission of children in the 6-14 age group to government schools had declined from 2006 to 2014. While 73.4per cent of children in this age group were enrolled in government schools in 2006, their percentage fell to 64.9 in 2014. It marginally increased to 65.9per cent in 2018 while enrolment in government schools accounted for 72.9 per cent in 2022.

“It is good that children have joined schools in larger numbers than before. But they need to be engaged meaningfully. What we see is that the time for teachers’ classroom transactions is about 30 percent of what is planned. The teachers get involved in midday meal, election duty and surveys. That takes away a lot of time,” said Dhir Jhingran, founder-director of Language and Learning Foundation, an NGO.

The propensity to seek private tuition is similar among children of government and private schools. While 30.9per cent children of Class I to VIII in government schools took private tuition, the corresponding figure for private schools was 29.7 per cent in 2022.

The proportion of children taking private tuition increased from 26.4 per cent in 2018 to 30.5 per cent in 2022.In Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Jharkhand, the proportion of children taking paid private tuition increased by 8 percentage points or more over 2018 levels.

Banerji said that like school enrolment, competition among students had also increased. Parents are also more concerned about the career of their children, which may have driven up enrolment and private tuitions.