Nullius in verba. Take nobody’s word for it.

If an iteration of the basic tenet of science — and several other pursuits in democratic societies — can never be out of place, contemporary India offers an appropriate backdrop for an encore.

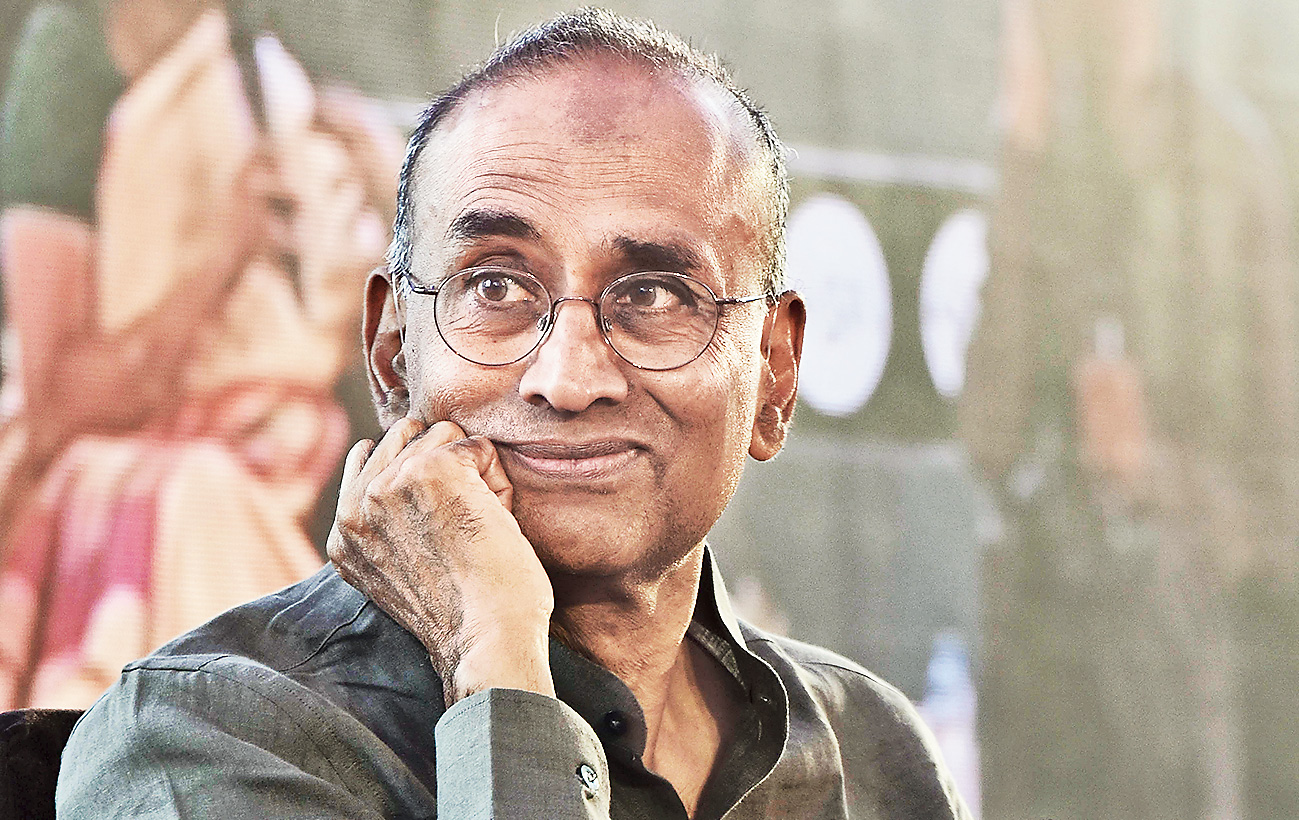

The reminder came from Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, molecular biologist, president of the Royal Society and Nobel laureate, in Calcutta on Tuesday.

“Art, literature and science are all ways of capturing some essential truth about the world. But science has some distinctive aspects. One of them is encapsulated in the Royal Society’s motto, which is Nullius in verba (take nobody’s word for it),” Ramakrishnan, who was conferred the Nobel for chemistry in 2009 with two other scientists, said after opening the Tata Steel Kolkata Literary Meet partnered by The Telegraph at the Victoria Memorial.

“In science, it doesn’t matter who you are or where it has been written but an idea is accepted only because it can be reproduced in experiments and can be tested. And it can be reproduced anywhere in the world with the required training and expertise,” he told a keen audience on the lawns of the marble monument.

In his own understated style, the soft-spoken scientist did introduce a contemporary element. “In an era of fake news where even the existence of objective truth is being questioned, there is much at stake. Science with its insistence of evidence-based fact offers a counter to some of these threats today,” Ramakrishnan added.

Later, a schoolteacher in the audience asked him how to improve science communication. “Because if something wrong is communicated it gets big headlines, like the recent science congress fiasco,” the teacher said. She did not specify what the fiasco was. At the 106th session of the Indian Science Congress in Jalandhar earlier this month, the vice-chancellor of a university said that the Kauravas of the Mahabharat were test-tube babies.

Ramakrishnan did not make any reference to any particular instance but replied: “I think we need more scientists or people with an interest in science… to become journalists.”

He did not say so but “nullius in verba” is also expected to be the single-most important guiding principle in newsrooms, which can weed out present-day pestilences such as fake news and headline management.

The scientist, who was mobbed by youngsters before he took the stage, pointed out that children were intensely curious about the world but rued that “somewhere along the way, people start taking the mysteries of nature and marvels of technology for granted”.

“Part of the fault lies in the way we teach science,” he added.

Ramakrishnan felt that science was more important than ever in the present times because “decisions are constantly made by governments, corporations, educators and others that affect us in profound ways” like energy consumption without causing climate change to maintaining privacy and security in the digital world.

For those who think an inquisitive spirit and a penchant to speak out against authority are esoteric concepts that have little bearing on a prosperous life, Ramakrishnan offered an eye-opener.

He said scientific knowledge created more wealth than colonisation did. His case in point was the advancement of Europe.

“This idea that science requires experiment and evidence and not authority… took hold as a result of the enlightenment in Europe… to think and speak out against authority… resulted in new ways of thinking and an explosion of knowledge and the Industrial Revolution. What it meant was that Europe quickly overtook China and India, which had dominated the world’s GDP for centuries.

“Those who ascribe the wealth of Europe to colonisation… might wish to consider that Sweden, Switzerland and Germany in 1900 were among the richest countries in Europe and had almost no colonies. Whereas Spain and Portugal were among the poorest countries in Europe and had a large number of colonies…. Actually, it is objective scientific and technical knowledge that creates wealth. That’s what it does even today,” he said.