Venkatraman Ramakrishnan won the Nobel in 2009. He was knighted by the Queen in 2012 and was elected president of the Royal Society in December 2015.

But Calcutta paid him the ultimate compliment in 2019 — pirated versions of his book, Gene Machine: The Race to Discover the Secrets of Ribosome, were available on College Street.

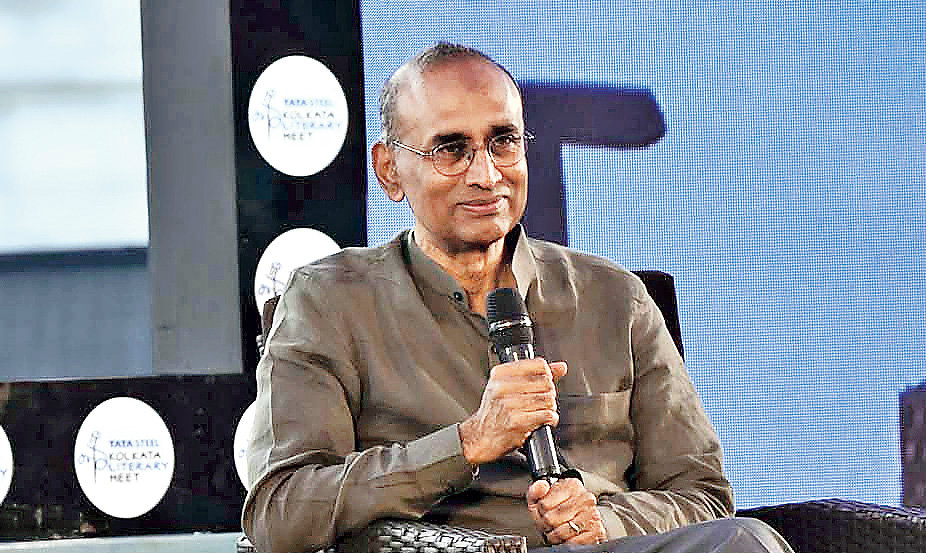

“I am told as an author you only know that you have made it if you find your books pirated on the streets of Calcutta,” the molecular biologist said at the Tata Steel Kolkata Literary Meet in association with The Telegraph and the Victoria Memorial Hall . He gave the inaugural address and took part in a session discussing his book with Anuradha Lohia, the vice-chancellor of Presidency University.

The pirated versions of Ramakrishnan’s books were available in Boipara bookstalls, Lohia said. “Venki, you have made it,” she told the author.

Good story

Much before he won the Nobel in chemistry in 2009, he knew the race to the award had a good story because it was fraught with rivalries and ambitions.

“When I was working on the structure of ribosome, it was an intense race. Even while it was happening, I thought this was going to be a good story someday….

“When people write about science… it is a highly sanitised version. People are following one logical step after another…. Real science isn’t like that.

“It involves mistakes, dead ends, competitions, rivalries, ambitions, egos — all of those things you find in a play or novel exist in the world of science…. I want to bring in science but also the scientists.”

Nobel syndromes

The scientist said there are two diseases with which Nobel laureates are generally affected.

Pre-Nobelitis: One is pre-Nobelitis, which scientists contract before winning the prize. “You are actually not thinking of the Nobel when you are working in the lab. But just as you accomplish something significant and you have a sense of satisfaction, people around you start saying ‘this is amazing and this could get the Nobel’,” the scientist-cum-author said.

Scientists generally travel around talking of their work, like it is some “political campaign”. Between 2000 and 2004, Ramakrishnan kept getting invitations to Sweden to talk about his work. “It was like an audition for the prize and I have seen brilliant scientists getting nervous doing these talks because they know they are speaking before the Nobel committee.”

Post-Nobelitis: He quoted Shakespeare in Twelfth Night, “some are born great, some achieve greatness and others have greatness thrust upon them” in describing how Nobel laureates are sought to give their opinion on everything under the sun outside their field of expertise.

Calling it post-Nobelitis, he said: “People treat Nobel laureates like a genius. I am asked about climate change. Now what would a person like me, a molecular biologist, know anything about climate change. Outside my field, I am as good as anybody else and in my field I am as good as my next paper.”

As if on cue, a member of the audience asked him about the state of Indian health care and if he has been sought to give his opinion on it. Venkatraman said: “There are enough experts on public health policy to guide the government on this quite ably and I will have no expertise to share on this.”

Often, Nobel laureates, he said, made a tidy sum giving lectures. “Its like a bit of a racket. There are invitations from Asia offering $20,000. When I mentioned this to my wife, she said ‘are we starving that we do anything like this?’ and in fact I quite felt ashamed to have even mentioned it,” the scientist who took a 50 per cent salary cut when he moved to Cambridge from the US said.

Arts and the man

Ramakrishnan spoke on the divide between humanities and the sciences that “have played many societies for a long time”. Too often at parties, he is asked “what do you do”.

He says he is a molecular biologist and studies how information in genes is converted into proteins. “That sounds fascinating. It’s terribly clever. I am afraid I was never very good at science and math,” is the stock response of most. The conversation then quickly moves on to the latest novel or concert, Ramakrishnan said.

“Now imagine the reverse. Somebody came to me and said they were a musician or an artist or a writer. And I said I know nothing about literature or arts or music really. I think people would then consider me an uncivilised bore,” he said, having the audience in splits.

“We should enjoy science and mathematics, all of us, because it is as much a triumph of human achievement and as much a part of our culture as history, literature, art or music.”