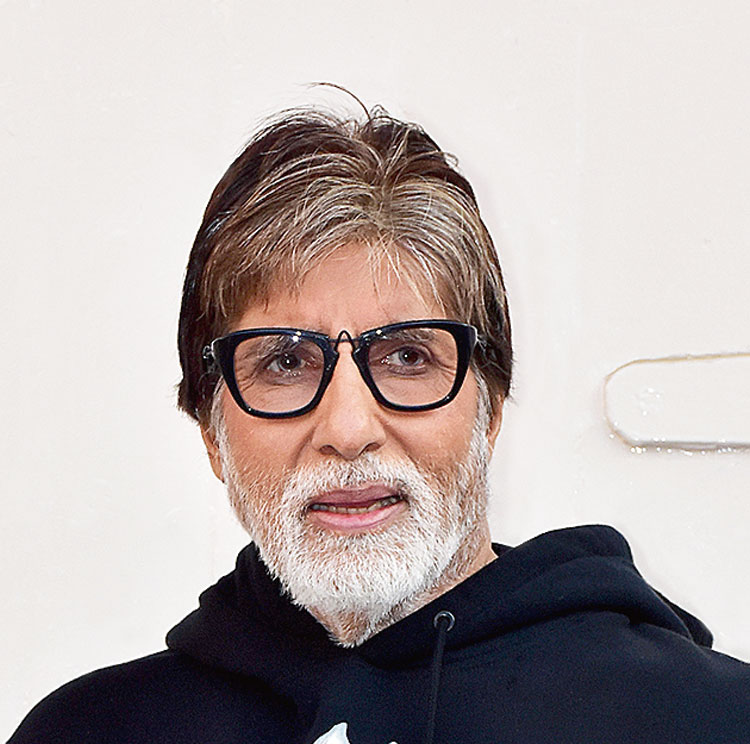

Last week, Amitabh Bachchan tweeted a still from his film Shahenshah (1988) and made a short remark on its remarkable opening despite the ban. Bachchan didn’t elaborate on it and tender social media addicts probably had no clue what he was talking about even if they “liked” his tweet a thousand times over.

With The Tashkent Files reviving memories of Emergency and Bachchan mentioning the ban, perhaps this is as good a time as any other to recall old stories of the many occasions when the undemocratic tool of banning someone fell on its face.

One of the earliest was when Dilip Kumar and Bachchan decided to teach journalists a lesson by gathering all their colleagues and banning the press. Their intention: to cleanse the colour yellow out of film journalism. However, the truth was that one of them was simmering because his furtive nikah to Asma, a married woman and mother of many, was called out with salacious details of how he as the sheriff of Bombay had used his official stationery to write romantic poetry to her.

Bans are rarely noble. They are mostly more personally vindictive than socially corrective. Hilariously, during this “ban”, a host of filmland colleagues that ranged from Rajesh Khanna, Dev Anand and Shammi Kapoor to Helen and Asrani either drove to the Sea Lounge at the Taj or called me over to their homes to give me as many interviews as I liked. They were essentially democratic people who resented the fact that their choice of who to talk to was being dictated to. But they didn’t want to offend Dilip Kumar by openly rebelling against him. Even the media-friendly Ashok Kumar did not agree with the senior actor.

With business almost as usual, except that one didn’t go to the studios as often, the ban died a quick death. To be fair to Bachchan, he learnt from it and never participated in any ban.

And then came Emergency. Very unwisely, once the Indira regime collapsed, five immature editors of five film magazines got together and decided to isolate Bachchan. In their heads, he had committed the unforgivable crime of using his clout with the Gandhi family to bring non-political film publications under V.C. Shukla’s pernicious censorship.

Singling him out, convincing one another that he’d been behind the censorship, and banning him from their publications was one of the most undemocratic and foolish decisions any journalist could take.

Karma was not on their side. Bachchan’s stars were in the ascendant and instead of celebrating his success and being a companion to him during his climb to the top, the magazines did themselves in. In a filmography of one of his co-stars, the editor famously told the sub at the desk to put a comma instead of his name.

In the pre-computer age, it was quite a task to manually ink him out of a group picture. Hurt by this, Bachchan began to stand at the far right or left to make it easier for journalists to cut him out.

It was during this time that Shahenshah was released. Meenakshi Seshadri, his heroine, had come in early and we were chatting in a corner when he strode into the music release function. He joined us politely. If I remember right, it was here that he playfully nudged his friend and director Tinnu Anand into the swimming pool. That made quite a splash.

Soon the magazines began to make sheepish overtures to him because he had become a superstar. But when they returned, he didn’t want them around. Showing strength of character, he didn’t go whining to his colleagues and asking them to support him or impose a ban on the press. He fought a long and lone battle until Bofors happened, the government changed and he decided to talk about the V.P. Singh regime hounding him. He thus neatly lifted the ban he’d imposed on those who’d unfairly banned him after Emergency.

More bans, more stories, another time.

Bharathi S. Pradhan is a senior journalist and author