Humans ruined everything. They bred too much and choked the life out of the land, air and sea.

And so they must be vapourised by half, or attacked by towering monsters, or vanquished by irate dwellers from the oceans’ polluted depths. Barring that, they face hardscrabble, desperate lives on a once verdant earth now consumed by ice or drought.

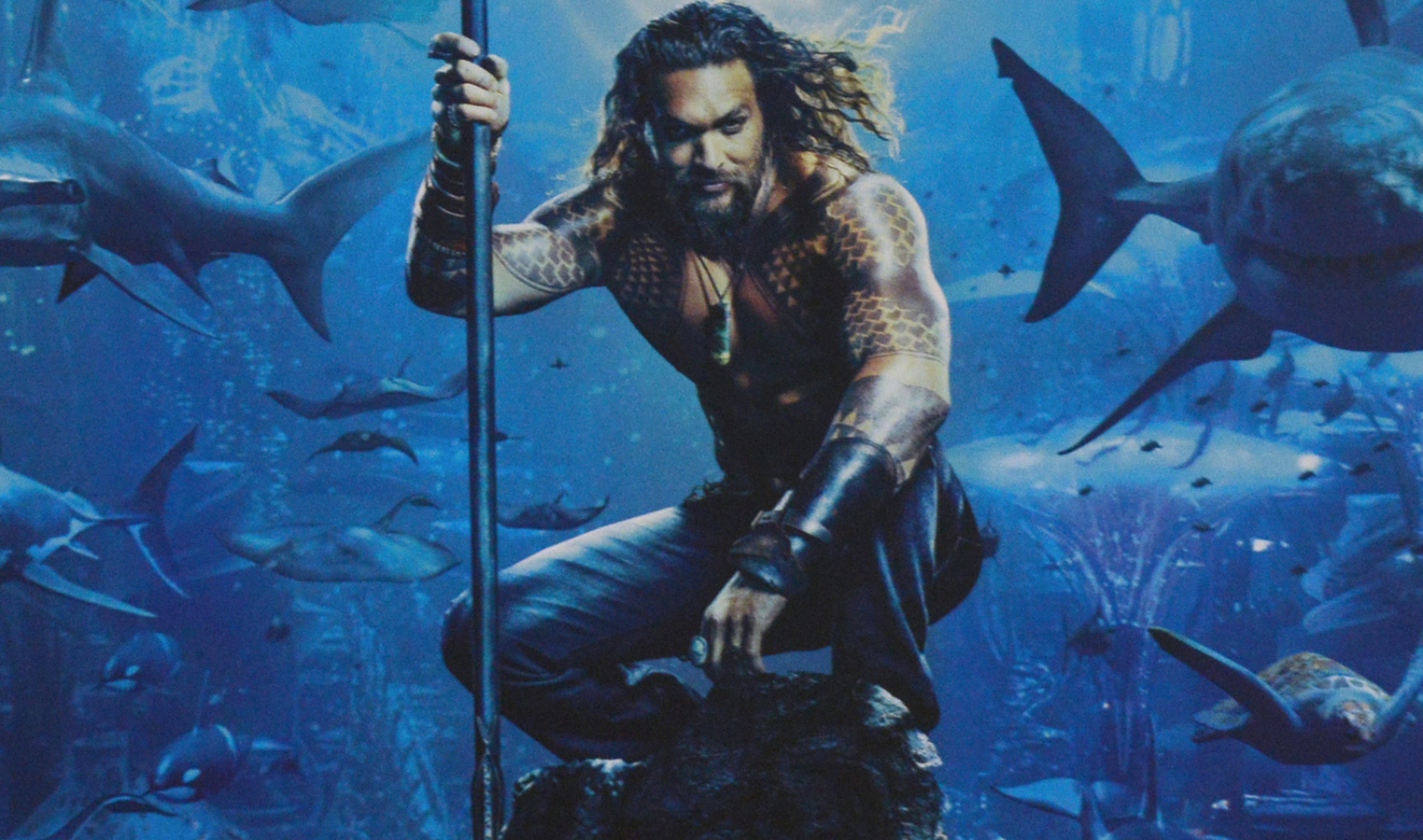

That is how many recent superhero and sci-fi movies — among them the latest Avengers and Godzilla pictures as well as Aquaman, Snowpiercer, Blade Runner 2049, Interstellar and Mad Max: Fury Road — have invoked the climate crisis. They imagine post-apocalyptic futures or dystopias where ecological collapse is inevitable, environmentalists are criminals, and eco-mindedness is the driving force of villains.

But these takes are defeatist, critics say, and a growing chorus of voices is urging the entertainment industry to tell more stories that show humans adapting and reforming to ward off the worst climate threats.

“More than ever, they’re missing the mark, often in the same way,” said Michael Svoboda, a writing professor at George Washington University and author at the multimedia site Yale Climate Connections. “Almost none of these films depict a successful transformation of society.”

Interstellar (Still from movie)

Polluters as bad guys

In Avengers: Infinity War, the archnemesis, Thanos, opts to head off environmental collapse by reducing humanity — along with all living beings — by half. In Godzilla: King of the Monsters, eco-terrorists unleash predatory beasts to forestall mass extinction and keep the human population in check. In Aquaman, King Orm, the leader of an undersea kingdom, concludes that the only way to prevent earthly destruction is to wage war on humans. David Leslie Johnson-McGoldrick, one of the writers of Aquaman, said using pollution as a motivator made Orm more relatable and less “moustache-twirly,” and added, “It gave him some nuance.”

But Svoboda sees Orm as part of a trend that moves the climate crisis into emotionally familiar and comfortable territory. The villain is defeated and the audience feels relief, he said, not least because they have been let off the hook: People may be doing real harm, but the alternatives are worse.

The trend of linking environmentalism to eco-terrorism is not confined to superhero and genre flicks, Svoboda said. In the 2017 indie First Reformed, Ethan Hawke plays a radicalised pastor who plots to blow himself up at a church service attended by a polluting industrialist.

“It plays into conservative talking points that environmentalists are out to reduce the pollution and restrict lifestyles and are genocidal,” Svoboda said. “They create mass murderers who are the only ones fighting climate change.”

In a contrarian piece for The Washington Post, the film journalist Sonny Bunch said as much himself, opining that environmentalists made for ideal bad guys because they want to make our lives worse by banning straws, large families, plane travel and red meat.

More sober takes on the subject, at least on the silver screen, have largely been confined to documentaries, which, with the exception of the 2006 Al Gore hit, An Inconvenient Truth, audiences and buyers mostly shunned. (On the small screen, docuseries and other shows often address the issue, but rarely break through in this age of peak TV.) One big studio feature that tackled climate change, The Day After Tomorrow, in which subzero superstorms envelope half the globe, was released 15 years ago. More recent efforts have foundered, like Alexander Payne’s Downsizing (2017), which imagined humans shrinking to the size of chipmunks to reduce their carbon footprint while still living large.

Svoboda pointed to Young Ones, a 2014 film starring Michael Shannon as a father eking out an existence in a drought ravaged world, as the rare film that showed humans adapting to global warming, but it barely made a blip.

The actor and director Fisher Stevens, who has made several documentaries about environmental issues, including two with Leonardo DiCaprio, said he found it deeply frustrating that Hollywood had not taken Big Oil to task onscreen in a significant way. “We need a pop culture Forrest Gump movie now to wake people up,” Stevens said, “because the fossil fuel industry is doing everything to stop us in America from believing that fossil fuels are causing climate change.” (DiCaprio, a committed environmentalist who has a foundation that tackles climate change, did not respond to a request for comment).

So why aren’t there more realistic, or semi-realistic, or, dare it be suggested, hopeful films about climate change? Because, several directors said, it is hard to find financing for movies that risk being real downers and challenge audiences to change their ways. Because mass extinction is soul-crushing and people seek out entertainment to escape.

Infusing narratives with hope

Because, said Roland Emmerich, the writer and director of The Day After Tomorrow, it is not easy to find a story that franchise-addicted studios will release. “We don’t do a good job,” he said, “And I’m constantly trying to figure out what could be another way to show it.”

Adam McKay, whose film Vice included references to the Republican Party’s minimisation of climate change, said the fact that the crisis was so large made it hard to fathom and to capture narratively. But he added that he was working on a new movie addressing the issue, and that his production company was developing a scripted series looking at the effect of radial warming on civilisation.

“Is any of this enough? No way,” McKay wrote in an email. “It seems like there’s no such things as ‘enough’ with global warming.”

On both sides of the Atlantic, there are efforts to change that and to infuse narratives with hope. Along with detailing how projects can reduce their carbon footprint during production, the Producers Guild of America, and, more emphatically, the British Academy of Film and Television Arts, are showing content creators how to incorporate green themes into their films and shows.

On the Producers Guild’s Green Production Guide site, a report by the Rocky Mountain Institute, a non-profit that promotes sustainability, lays out ways renewables can be portrayed onscreen. Some suggested plotlines come with a wink, ranging from showing characters who go off the grid to philanderers who fall for their solar-panel installers. The point, said Jacob Corvidae, one of the report’s authors, is to relay how robust the clean energy sector is, and also to sow hope. “We do need depictions that things could be okay. because people worked at it,” he said.

This spring, BAFTA released a study showing how many times ecological terms appeared on British television in one year (the report did not include film). “Climate change,” for example, appeared more than “zombie” but trailed “gravy,” and was utterly trounced by “queen” and “tea.” The academy also started an initiative, Planet Placement, exhorting film and television content creators to help “make positive environmental behaviours mainstream.” With screen industries’ massive reach, they said, “it’s a chance to shape society’s response to climate change.”

“The past 25 years of the environmental narrative is about sacrifice and doom and not doing what you want and not getting what you want,” said Aaron Matthews, head of industry sustainability at BAFTA. “We don’t think that’s the right tone to get people over the line.”