‘Baarish hotee hai toh paani ko bhi lag jate hain paaon’. Gulzar’s experiments with poetry give rise to many delightful images, of which this is a favourite for the way it renders the rains a living, breathing entity with playful feet that go running. As he mentioned in an interview, the monsoon is ‘the most physical of all seasons, a season you can touch and see’, one that makes him write ‘a trifle too personally’. He has engaged with the rains in a number of his non-film poetry. Though there is the odd poem that brings out the joy of the rains, say, for example, in this where he juxtaposes the playfulness of the rain with that of young boys returning home after winning a game:

Baarish hotee hai toh paani ko bhi lag jaate hain paaon

dar-o-deewaar se takra ke guzarta hai gali se

aur uchhalta hai chhapakon mein

kisi match mein jeetey hue ladkon ki tarah

Jeet kar aate hain jab match gali ke ladke

joote pahne hue canvas ke uchhalte hue gendon ki tarah

dar-o-deewaar se takra ke guzarte hai

woh paani ke chhapakon ki tarah

A number of his musings on rain come with a melancholy that no one gets better than Gulzar. Consider: ‘Kaise chup chaap barastaa hai musalsal paani’ (‘Jhadee’, How the silent rain falls, steadily) or ‘Dekh kaise baras raha hai udaas paani’ (‘Seelan’, See how the sad rain pours). Few poems convey the sense of steadfast rains (‘Bas ek hi sur mein, ek hi lay pe’) weaving it sensuously with its ability to evoke memories (‘Dimag ki gili gili socho se bheegi bheegi udas yaade tapak rahi hain’) and the warmth of a lover’s fragrant breath:

Bas ek hi sur mein, ek hi lay pe

subah se dekh, dekh kaise baras raha hain udaas paani

phuwar ke malmali dupatte se ud rahe hain

tamaam mausam tapak raha hain

palak palak ris rahi hain ye kaaynat saari

har ek shay bheeg bheeg kar

kaisi bojhal si ho gayi hain

dimag ki gili gili socho se

bheegi bheegi udas yaade tapak rahi hain

thake thake se badan mein

bas dheere dheere saanson ka

garam lobaan jal raha hain

He creates this pensive longing for rains in his film songs too. A film song of course involves factors like the situation and its picturisation, the tune, the singer; however, Gulzar brings his own aesthetics to it that make the song stand as a work of art independent of every other aspect associated with it. And like his poems, many of these songs throb with a sorrowful yearning that seeks to break free of the constraints of the spaces in which the song is picturised.

Interestingly enough, every song here approaches the rain from the perspective of the woman, not surprising given his unique understanding of the feminine psyche.

Sawan Ki Raaton Mein (Prem Patra, 1962)

The beauty of Gulzar’s words — ‘Sawan ki raaton mein, aisa bhi hota hai, raahi koi bhula hua, toofano mein khoya hua, raah pe aa jaata hai’ — in this remake of the Uttam Kumar-Suchitra Sen-starrer Sagarika lies in the fact that they lend themselves to both interpretations: a soul lost in a tempestuous storm finding his way, or that despite the torrential downpour, one does come across a lost soul on the way. Evocatively shot — the coconut trees in the background heady with the rain-laden breeze — to Salil Chowdhury’s exquisite composition, this is a remarkable love song. Just consider how the poet invites the beloved to partake of the storm rising in his heart:

Toofan yeh meray dil se utha hai

Chaho toh tum inhe daaman mein bhar lo.

Jhir Jhir Barse (Aashirwad, 1968) / Bole Re Papihara (Guddi, 1971)

Vasant Desai’s finest moments in Hindi cinema. The longing for the beloved to return home, accentuated by the rain, has seldom found better expression. Lata Mangeshkar scales new heights with the Gaud Malhar-inspired ‘Jhir jhir barse’ in which Gulzar renders the rain both agonising and mischievous — ‘Reshmi boondiya tan pe maare, chhed kare bheegi bouchhare’ (while the silky raindrops slap the skin, the wet splash of water flirts). Like a number of other songs which connect the rains to tears, Gulzar does the same but in his own inimitable way: ‘saawani ankhiyan’ (monsoon-laden eyes) is how he describes it.

In ‘Bole re papihara’, based on the same raga, the cuckoo’s yearning for the monsoon is juxtaposed with a child-woman’s rising awareness of her desires. The words are pure gold when you consider how a cuckoo will die of thirst waiting for the rain but not partake of river water. The lover, like the cuckoo, waits, adorning her eyelash with a drop of water, for the monsoon to take it away and rain over the beloved’s land: ‘Palkon par ek boond sajaye, baithi hoon saawan le jaaye, jaaye pee ke des mein barse.’

Mujhe Jaan Na Kaho (Anubhav, 1971)

Gulzar’s evocative words and Kanu Roy’s gorgeous composition make for one of the most memorable rain songs in Hindi cinema. The raindrops cascading down windowpanes and the fresh, rain-bathed plants outside give the sense of newly discovered love. The imagery is sensual – ‘honth jhuke jab hothon par, saans uljhe jab saanson mein’ – and yet there’s a sense of the pristine longing of new love and how the rains heighten the pain of separation. Note the play of words contrasting a ‘dry monsoon pouring from the eyes’ and ‘wet eyes that fail to shed even a drop’: ‘Sookhe saawan baras gaye, kitni baar inn aankhon se / Do boondein na barsein, inn bheegi palkon se.’

Abke Na Saawan Barse (Kinara, 1977)

A song of great despair where again the poet likens the missing monsoon to the tears that flow unabated. Without the beloved, the season loses all its meaning as Gulzar says:

Jane kaise ab ke yeh mausam bitey

Beetegi jo tere bin woh kam beetey

Tere bina sawan sooney

Tere bin ab toh yeh mann tarse.

Jaane Kaise Beetegi Yeh Barsaatein (Baseraa, 1981)

Another vintage RD Burman-Gulzar song that has not received the attention it so deserves. Here the poet considers the impossibility of surviving the monsoons, living on borrowed days and nights. Like in a number of his rain songs, we have the poet pulling off the impossible in describing tears as wet (‘geeley aansun’) as if there is another kind. Not only that, these wet tears smoulder and the rain sets everything on fire: ‘Dhuan dhuan sa rahta hai, bujhi bujhi si ankhon mein, sulag rahey hain geeley aansun, aag lagati hai barsate.’

Phir Se Aiyo / Badi Der Se Megha Barse (Namkeen, 1982)

RD Burman’s Raag Malkauns-inspired composition, ‘Phir se aiyo’, is just what the doctor ordered for Gulzar’s soulful lyrics communicating in the same breath a world of pathos and pleasure in waiting for one’s love. There is no rainfall in the sequence whatsoever but the elegiac picturisation and RD’s melody echo a valley bathed in rain. And Gulzar’s words – ‘Tu jo ruk jaaye meri atariya, main atariya pe jhalar laga loon… chhu ke jaiyyo hamari bagichi, main peepul ke aade milungi’ – is as much a plea to the clouds as it is to the beloved to return.

In the adulation ‘Phir se aiyo’ has received, ‘Badi der se’ remains uncelebrated. A rare mujra collaboration between Gulzar and RD Burman – that makes use of the semi-classical folk genre of Chaiti – the words here, describing the rains as alternating between lazy and vigorous, and again relating it to teardrops, convey the futility of an eternal wait:

Thoda sa tej kabhi thoda sa halka

Roka na jaaye mui akhiyon ka tapka

Jagi rahi leke hatheli pe bheegi ladiyan

Jali kitni ratiyan.

Chhoti Si Kahani Se (Ijaazat, 1987)

Another triumph in all respects, this gem plays with the film’s opening credits and is thus devoid of an essential element of a film song. That it manages to convey the spirit of the rains despite that owes itself not just to the genius of its lyricist, but the ability of its composer to give the words just the right touch. Gulzar has never been better than when he says, ‘Shakhon pe patte thay, patton pe boondein thi, boondon mein paani tha, paani mein aansun thay’, tracing a path from the branches to the leaves, to the raindrops that adorn those leaves, the water that makes up the drops, and the tears that lie at their heart. Or the way he conveys the soul of the monsoons in the lines ‘Rukti hai, thamti hai, kabhi barasti hai, badal pe paon rakhkhe barish machalti hai’ (the rain trembling restlessly on the clouds!).

Tann Pe Lagti (Astitva, 1997)

Exactly a quarter-century after the almost-innocent intimacy that informed ‘Mujhe jaan na kaho’ in Basu Bhattacharya’s Anubhav, the director’s final film takes the sensuousness more than a few notches higher. This is Gulzar at his erotic best, finding a link between the rains and raw physical desire for the beloved. His imagery likens the raindrops to shards of glass, fiery splinters that are colder than ice. And while ‘long-limbed’ raindrops caress the body (‘baarish lambe lambe haathon se’), comes the punchline: if only the breath, laced by the lover’s fragrance (‘lobaan si saansein’, which harks back to the non-film poem at the beginning), stopped for a bit.

Tann pe lagti kaanch ki boondein

mann pe lage toh jaanen

barf se thandi, aag ki boondein

dard chhuge toh jaanen

baarish lambe lambe haathon se

jab aakar chhooti hai

ye lobaan si saansein thodi

der ruke toh jaanen

The song conjures passion in multiple hues, for example, ‘laal sunheri chingari… gulmohar ki laptein’. Not many poets would have used ‘chingari’ and ‘laptein’ when speaking of gulmohars.

Geela Geela Paani (Satya, 1998)

How else do you visualise water if not ‘wet’? Trust Gulzar to make a fetish of even the rains being wet. Aided by Vishal Bhardwaj’s mesmerising composition, Gulzar actually makes the rain hum: ‘Ni pa, pa ni, gungun karta paani’. He even uses the phrase ‘hoom hoom’ for the way it pours over the cityscape. The song’s second line ‘paani sureela paani, paani’ establishes the rhythm of the falling rain, as he goes on to give wings to his flights of imagination.

Raindrops beat against the windows, the droplets caress the face, the lips taste the water in the heart of a droplet: ‘Honthon ne chakkha paani boondon mein rakkha paani.’ In his imagery, the sky overflows, and the heart is almost criminal, sinful in the desires it nurtures: ‘Ruk ruk ke chalta hai yeh dil, mujrim sa lagta hai yeh dil.’

Barso Re Megha (Guru, 2007)

Of all Gulzar’s songs celebrating the rains, this one holds the least appeal for me. The fault lies not with the words, which are as eloquent as any of the other songs here, but with Aishwarya Rai Bachchan’s ‘acting’ and A.R. Rahman’s composition. None of the other songs in this list have the actors getting drenched in the rains and yet each conveys the essence of the season. In this, the actor is so over the top with her expressions and the composition so synthetic that Gulzar’s flourish with words fail to rise above these limitations. He is in vintage form as he compares the sweet warmth of the rain to a kiss: ‘meetha hai kosa hai, baarish ka bosa hai’. Before going on to describe the grandeur of the rains in the dark of the night and the sheer ecstasy of letting it sweep you away:

Kaali raaton mein

Yeh badarwa baras jayega

Gali gali mujhko megha doondhega

Aur garaj ke palat jayega

Ghar aagan agana aur paani ka jharna

Bhool na jaana mujhe sab poochhenge warna

Re beh ke chali main to beh ke chali

Re keh ke chali main to keh ke chali re megha.

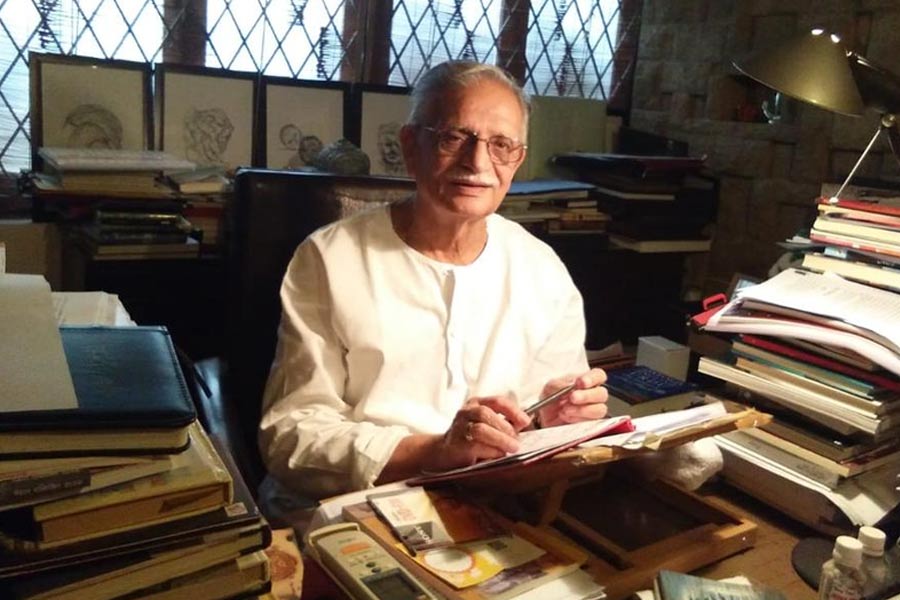

(Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is a film and music buff, editor, publisher, film critic and writer)