Deepti Naval. For a generation of a certain antiquity, the very name lights up incandescent memories. I first watched her in the delightful Chashme Baddoor as a 13-year-old. Her Miss Chamko in the film remains one of Hindi cinema’s most memorable acts, but it’s her emoting to Kahan se aaye badra that pulled at my youthful heartstrings, leading to my first ‘star’ crush. For a few years in the early 1980s, her films like Saath Saath, Rang Birangi, Katha, Kisise Na Kehna, Kamla and Ankahee, among others, promised a new spring in the arid deserts of Hindi filmdom of the era. There was something comforting, something approachable to what she brought to those films and characters.

That spring proved illusory and Deepti Naval moved on to make a name for herself as a photographer, a painter, a writer and a poet, though she kept a foot in Mumbai, acting in films like Mirch Masala and Memories in March, and in recent times directing the well-regarded Do Paise Ki Dhoop, Char Paise Ki Baarish and making a splash with her performance in Listen… Amaya.

Today, 40 years later, as I meet her for the first time, to talk about her recently published memoir, A Country Called Childhood, I am reminded of my first impression of her. The last days of my childhood, illuminated with that ‘Miss Chamko’ smile. Given her work as a poet and the lyrical tenor she brings to her memoir, I decide to frame the interaction with poems by Rainer Maria Rilke. In my view no one captures the essence and the tumult of childhood better than Rilke. It’s also fitting because despite calling A Country Called Childhood a memoir, Deepti Naval is categorical about ‘poetry being the only autobiography I am going to write’ – and indeed begins her memoir with a poem.

The book cover. A Country Called Childhood

So, as Rilke says in ‘For the Sake of a Single Poem’, ‘You must be able to think back to… days of childhood whose mystery is still unexplained, to parents whom you had to hurt when they brought in a joy and you didn’t pick it up (it was a joy meant for somebody else); to childhood illnesses that began so strangely with so many profound and difficult transformations….’ How do you look at your childhood?

Deepti Naval: It was the best part of my life. And when I say that I know many people will identify with that statement… many of us feel that there has never been, there will never be a phase like our childhood. It was memorable, and more importantly, it was exciting. There was enough happening there to fire my creative instincts as a writer. If I was to do creative writing other than poetry, what would I like to write about? It was an extension of my poetry. Since I write a lot about my personal stuff, I thought I would like to recreate for the reader the world that made me who I am. Go through my childhood days in a way that my reader can travel with me along those corridors and bylanes and get a glimpse of what my childhood and that era were like.

There is something very cinematic in the way you structure the narrative. You begin with a dramatic ‘pre-credit’ prologue, evocatively titled ‘The Dance of Songs’, and then the text unfolds almost like fade-ins and fade-outs. Was this something thought out or did it grow organically?

Deepti Naval: I kept jotting down my memories. Randomly. It was strung together by my editor and publisher, David Davidar. He is the one who helped me structure it into a book. I simply kept making a note of the various phases – the school years, the teenage years….

Given that it is quite a huge tome, how many years did it take to put it together?

Deepti Naval: Well, intense writing was for the last five years, but the work on this book began long ago. The first four chapters were written 20 years ago. Then I realised that the chapters that come to me easily are not going to form my entire book.

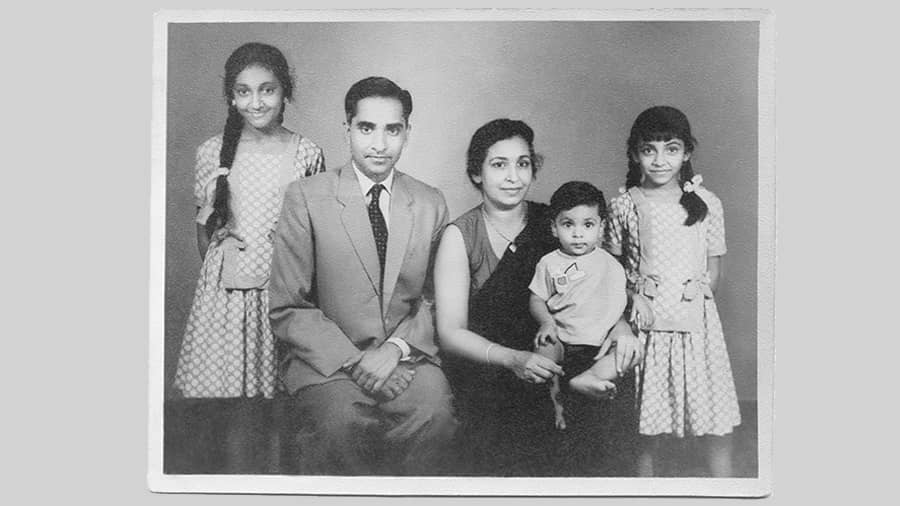

Family. A Country Called Childhood

What are these chapters that came easily?

Deepti Naval: The one on my friend Neeta Devichand. The Indo-Pak war of 1965.

Really? I would have thought that would require a lot of research?

Deepti Naval: No, no, all memory. My impression of the war. Later on, I cross-checked to fill in the gaps, but in the writing flow, it came easily. The patriotic songs, the trucks passing by, the mochistan kids running into the trenches, the jet sabres. My father switching the light on, Mama putting it off, Didi switching it on again. The whole hullaballoo of it. Someone telling my father, “Professor sa’ab, aapke ghar se koi Pakistani jets ko signal de raha hai!” That came in a flow. As did the chapter ‘The Elbow Crusade’.

For the uninitiated, this chapter deals with an ‘infantry’ that Deepti and her school friends raised and the tactics they employed to deal with ‘eve-teasers’, something she also terms the ‘chappal and jooti offensive’. A delightfully wry take on what it takes to deal with this age-old problem.

Deepti Naval: I didn’t want to make it dreary. I wanted to talk about things that all girls suffered from.

People don’t know me – they see me in the lovely image of a role I have played. I am not those roles, those characters. If you understand the child that I was, you would have a fairly good idea of what I turned out to be later. You are connecting with the real me if you can see the road to the country of my childhood.

Deepti Naval

Not much has changed, has it?

Deepti Naval: Of course it has – things have become even worse, if that were possible. Earlier it used to be an irritant. Now it’s criminal what girls have to go through. It used to be traumatic, humiliating, but now it has taken on dimensions that are unpardonable. So, my book was going to be about my entire childhood. What stands out in my head, in my memories, the highlights, the passing visions. There were lots of things that needed research, cross-checking, several trips, even to Lahore, Jalalabad, work on the photographs, sourcing them, selecting the ones to use.

Was it a conscious decision to have the photographs integrated with text on text paper, instead of creating a separate section on art paper?

Deepti Naval: A lot of work went into the selection of the images. I wanted them to tell a story of their own. I think they would have looked much better on special art paper, but it was also essential to weave the photographs with the text. Above all, I wanted to probe what my exact feelings were about those chapters of my life, I wanted to be true to that. Is this what I really felt?

The book is redolent of the sounds and sights of the place and the era. It’s very visual – do you actually remember all this in such detail?

Deepti Naval: Oh yes, absolutely. The house had a character of its own. I can still see it in my mind’s eye. I started making notes around ‘Life in the Chandraavali house’, these snippets, the sound of the itinerant vendors, the dust storm, the many stairs the house had… and then fleshed them out with what they evoke in me…. I wanted to share all this. I know that world is gone.

Even a humble piece of furniture, a hatstand, gets pride of place in the narrative.

Deepti Naval: It’s the only piece of furniture I retained after the house got sold. It is a witness to my coming of age. I did not want to visit these places, say, Jallianwala Bagh, before I was done writing the book. I wanted to convey the memories from that time which were stark in my mind. The summer afternoons. I remember them in a light all my own. We would draw the chik and the veranda would be a chiaroscuro of light and shade. The thandi farsh. We would all have our afternoon siestas, and in the middle of it, my buas would get up and sneak out, get their makeup on, different shades of red lipstick, comb their hair – and all ready to go out for the matinee show.

The book is plotted with some memorable characters made more so in the way you narrate it. The little dark-skinned, wide-eyed boy with a bowl, for example.

Deepti Naval: That memory I remember so clearly. I felt so sorry for him. We had no milk to give him. That was the first time I probably felt empathy for someone – of course I didn’t know the term at the time. What I remember is this: In my mind’s eye I am seeing a frame – I am standing next to my mother, and the boy is down there. And I am actually looking at this frame from up there. I was looking at myself, looking at the boy. There was my first crush… I used to imagine him speaking to me, asking me my name, telling me his name. Young-girl fantasies. Then one day, I was walking down the street with my father. I see him at this window, with a datun. And I said, What! He does not even have a toothbrush! Such innocence. Today we go to high-end department stores to get these organic datun, imagine!

There are a series of fascinating people you characterise as possessing a freedom of the spirit.

Deepti Naval: You know, when you are not quite toeing the line, you have gone off socially dictated norms, there’s a freedom that comes from it. Of course, they don’t know about it. But as a child I was curious. The understanding came much later. I was always interested in the underdog, the people in the margins. Even my short stories are seldom about ‘normal’ – whatever you define that as – people. I am interested in the aberrations.

And Neeta Devichand was obviously a big ‘aberration’?

Deepti Naval: She was a big influence. Had a profound impact on me. This was my first experience of dealing with someone who had that ‘imbalance’ – later of course I would study, I took up abnormal psychology as a subject, and get acquainted with chemical imbalance that upsets one’s mental equilibrium. How was it possible for someone to put her hand in the hinges and bang the door and be okay with all the bleeding, the pain? My first experience of what a mental asylum was like. And all this over 50 years ago, when talking about mental issues was absolutely unthinkable. She also provided me my first understanding of alternative sexuality. At that time, none of us had heard the term ‘lesbian’. I discovered that only when I went to America and read the poetry of Sappho. And it washed over me: wasn’t that Neetu’s condition? I still called it a ‘condition’ – even in America it was not an accepted thing those days. I have tried to deal with all these things which went into making me what I am.

Indu and I. A Country Called Childhood

Taking off from the ‘madmen of the spirit’, there’s a very interesting take on the blurring of the lines between reality and make-believe, particularly in what I think is the most impactful chapter of the book, ‘My Imaginary World’. Was there a part of you that was, for want of a better phrase, ‘out-of-normal’?

Deepti Naval: I am so happy to hear this from you. There must have been a part of me that was not quite there, which kind of attracted these experiences.… In my head I had different names for buffaloes, there was Charlie, Brownie, Bhuri, Gango…. As much as I lived my outer world, I lived in my inner world, maybe even more in the inner one. I convinced myself, it was not my imagination, I actually believed that my mother had told me that we used to live in that yellow house by the railway track. I was fascinated by that… powder-pink train, puffing white clouds of smoke, gliding by feather-like, soundless on water tracks… at one point I remember David Davidar telling me that there was no way he could put all that in the book, it didn’t fit in the narrative.… I told him that without my imaginary world, the picture of my childhood isn’t complete. So, instead of trying to fit it here and there, I made a separate chapter. This is the child I was; I would take up the real, fictionalise it, create a world of that in my imagination, and live that.

Was running away from home part of that imaginary world?

Deepti Naval: Yes, I think so. I had a streak in me that was quite ‘abnormal’. Otherwise, how could I so easily, without a thought, keep on doing these things? And the characters – Bae is the real person, I made her Bebbe in my world – and then planted her on top of the house, sitting at the very edge of the terrace, observing the world, while I ‘observed’ her. The real Bae fell off the terrace and died. I recreated her death – for Bebbe. Falling… floating in the wind, dancing in the wind like a song.

You also mention putting a matchstick to your diaries. Was that part of this streak?

Deepti Naval: No, no. (Laughs) There was nothing in the diaries. I just felt like being this drama queen – it’s an important thing to do, let me burn my diaries (laughs). Otherwise, it was full of banal stuff – I am not speaking to Didi, today Mama told me this, it was supposed to rain but it didn’t, that kind of everyday things. But the drama of burning the diaries was impossible to resist, maine na apni diary jala di… you can imagine the way I thought that line would sound. I was trying to create stories.

So, you have been an actor, a poet, an artist, a photographer, a filmmaker, a writer and now a memorialist. Where does one find Deepti Naval?

Deepti Naval: Umm… I think a little in all of these. So far, today, as of this moment, I feel this book is truly me. Because if you understand the child that I was, you would have a fairly good idea of what I turned out to be later. You are connecting with the real me if you can see the road to the country of my childhood. Poetry, for all its eloquence, often does not reach the reader, unless the reader takes the time, makes the effort to dive deep into the poet’s mindscape. Poetry hides the person. People don’t know me – they see me as this sweet character in numerous films. That’s not me at all. People see me in the lovely image of a role I have played. I am not those roles, those characters. I am a sum of all those experiences that gave birth to the dark side of my poetry, and now this book.

Saree first time: Kullu dress. A Country Called Childhood

Since we began with Rilke’s poem, I would like to end with one. Rilke says, ‘I prayed to rediscover my childhood, and it has come back, and I feel that it is just as difficult as it used to be, and that growing older has served no purpose at all.’ Has growing older served any purpose for you?

Deepti Naval: I do not agree with him here (smiles). It has served a singular purpose. It has made me cherish what I took for granted at that time. Made me value and realise what my parents were… it gave birth to my first essay ‘Little woman and the Gramophone’ which I mention in the book… what they did to enrich our lives… the enormity of that statement my mother made – ‘I silently gave up everything’. It never struck me at the time what that meant. It was only later when I became an artist, working towards my dream… oh my god, would I have ever been able to give up whatever I valued. I don’t think so. I would have fought till the end. That perspective came with age, with growing older.

We have come to the end of the interview and I realise I have not asked her a single question about her cinema. Well, there’s always another day – and with Deepti planning a memoir on her journey in cinema, inshallah, that day is not far off.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is a film and music buff, editor, publisher, film critic and writer. Books commissioned and edited by him have won the National Award for Best Book on Cinema twice and the inaugural MAMI Award for Best Writing on Cinema.