Before we get to the story of Bheed, it’s imperative to know the story behind Bheed. Ever since the trailer of this Anubhav Sinha film — that chronicles the plight of migrant workers on a mass exodus during the sudden Covid-19-induced lockdown in March three years ago — dropped, systemic machinery has been in place to brand it “anti-national” (now where have we heard that before?) Reason? Sinha, known for cinema that lays bare the uncomfortable truths of our society, compared the migrant exodus of 2020 to the Partition of 1947, drawing an allegory between those in the present forced to leave their homes to those in the past compelled to leave their country. In a pre-emptive response, a prominent production house backed out of the film’s publicity at the nth minute, even as Bheed’s trailer was taken off for a few days and then brought back, with the Partition comparison erased. Bheed is now playing in cinemas with a reported 13 cuts/edits ordered by the censor board.

But Sinha’s voice is not one to be muffled. Even in its edited version, Bheed screams out loud and clear. Sinha, true to the film-making style he has come to be known for in films like Mulk, Article 15 and Thappad, makes his latest a visually stark, and often horrific, reminder of a humanitarian crisis which not only exposed the inept disaster management system of the country but also became fertile ground to uncover the deep schism between the haves and the have-nots, with class conflict, caste-based politics and religion-induced discord having a free run, even as millions of helpless, unprivileged Indians fought and struggled for a basic right — to return to their homes.

Shot in black-and-white, Sinha’s intention to name his film Bheed is revealed within its first few minutes. Even as an upright TV reporter (played by Kritika Kamra) captures the mass exodus on camera, her eyes fall on a truck slowly inching forward, the goods that it’s carrying on its back proving too heavy for the flimsy jute cover over it. When society splits at the seams, like in the case of the jute cover, it becomes a bheed, a crowd with no control, organisation or one to call their own, is what Bheed says.

In many ways, Bheed is a companion piece to Article 15. If that film, that ripped the lid of chasms brought on by caste conflict, started with Bob Dylan’s powerful voice singing How many roads must a man walk down before you call him a man? from Blowin’ in the Wind, then Bheed opens with a Bob Marley line from Buffalo Soldier: ‘If you know your history, then you would know where you coming from’. That line, in many ways, tells us what Bheed, with its story written by Sinha along with Saumya Tiwari and Sonali Jain, wants to say: that our past informs our present, the state of present-day India seen through the prism of a health crisis which soon turns into a socio-economic tragedy.

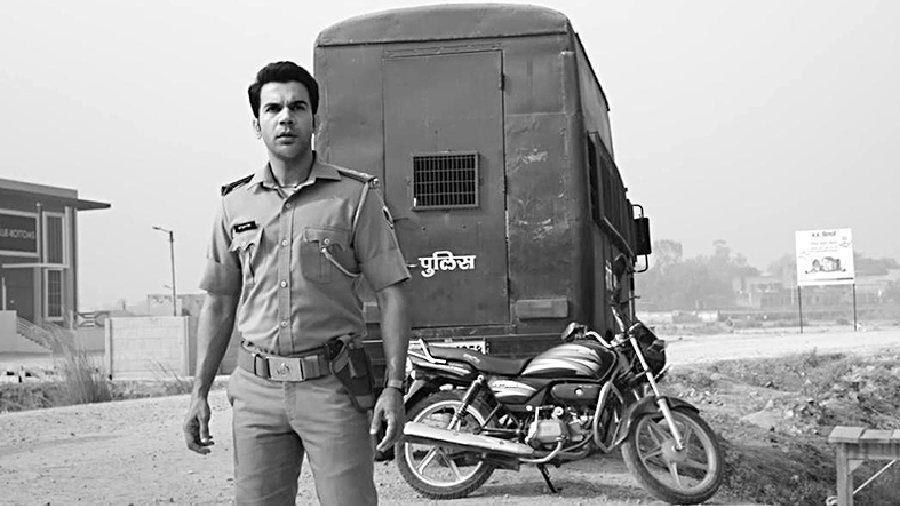

Bheed comprises an ensemble cast, but is well and truly headlined by Rajkummar Rao. He plays a young cop, his Dalit identity hidden behind the acquired name of Singh, who is given the charge of a crucial checkpost close to the village of Tejpur in Uttar Pradesh in the early days of the migrant exodus. What plays out at that checkpost through the period of one day becomes a microcosm of millions of checkposts that sprung up across the country, where migrants — exhausted, helpless and bleeding — landed up, only to be told that they couldn’t go further. The simmering tension gives way to a face-off that becomes desperate and ugly, with humanity lost, found and lost in many ways.

Bheed walks the thin line between fact and fiction, peppering its imagined circumstances taking place at its setting with real-life accounts that happened during the migrant crisis. Like the horror of tired migrants sleeping on the tracks being run over by a train to many of them being sprayed with pesticide in public. There is also the courageous story of the girl who cycled 1,200km, with her father riding pillion, to her home.

But such stories of resilience are few and far between and Bheed rightly presents what is a grim account of a blot in India’s history that, three years on, most of us seem to have forgotten. Soumik Mukherjee’s lens, leached out of all colour, presents this harsh truth — crying faces in close-up to bleeding feet and torn nails — as much as Sinha’s writing does. A mall within sniffing distance of the checkpost becomes the setting as well as the instrument for Bheed to tell its story of the deep divide that exists between us, with the mall becoming an emblem of the growing disparity between the privileged few and the many who aren’t.

Bheed is powerfully told and pulls no punches, but does lose itself to the perils of long stretches of repetitive nothingness, even within its compact run-time of 112 minutes. What holds it together, apart from Sinha’s intent of film-making as an act of defiance, is its performances, with every player — Rajkummar to Pankaj Kapur, Bhumi Pednekar to Dia Mirza, Ashutosh Rana to Aditya Srivastava — embracing their parts like second skin. The actors feel their parts rather than play them out, and that’s where Bheed’s true triumph lies.

Bheed ends without a denouement, simply showing the migrants living another day to tell their story, even as certain realisations take place across both sides of the divide. And we are left with a line that springs up somewhere in the middle of the film: “Justice is always in the hands of the powerful. If the powerless served justice, then justice would be different.”

I liked/ didn’t like Bheed because...

Tell t2@abp.in