‘My film is loosely based on the trial famously known as Monkey trial or Scopes trial. And just like the way that trial was used to develop a play and the movie Inherit the Wind in the McCarthy era of the USA, I developed A Holy Conspiracy in an Indian context. We are witnessing more or less the same kind of situation in our country’ – Saibal Mitra, filmmaker

It says something about the state of the nation that a trial on faith and science in the America of the 1920s, and a 1955 play written by Jerome Lawrence and Jacob E. Lee as a reaction to the McCarthy-era witch hunts, remains so relevant to India in 2022, that too a small tribal hamlet in the back of beyond.

It also says a lot of the writer/filmmaker who makes this adaptation work so seamlessly for the most part. Saibal Mitra’s A Holy Conspiracy is that rare contemporary film. One that addresses burning issues facing our nation – fanaticism, religious bigotry, superstition and pseudo-science – without beating about the bush, without sugar-coating it in any way, without pulling any punches.

In the ‘Scopes Monkey’ trial of 1925, teacher John T. Scopes was prosecuted for violating Tennessee state’s Butler Act, which prohibited the teaching of evolution in public schools. In Mitra’s adaptation, Kunal Joseph Baske (Sraman Chattopadhyay), a teacher in Hillolganj, a small, Christian-majority Santhal town on the Bengal-Jharkhand border, is charged and jailed for a similar offence. Only not quite.

There are other factors at play here. Given the realities operating in the Indian landscape today, it goes beyond a simple matter of faith and science. Vested political interests are at play, muddying the waters. There’s a book on Vedic science in ancient India – advocating things like Rishi Kanad discovering the laws of motion aeons before Newton, Rishi Bhardwaj developing airplanes well before the Wright Brothers – that’s been surreptitiously introduced into the curriculum. There’s the issue of the local tribals having converted to Christianity and the ‘ghar-wapsi’ programmes underway to bring them ‘back into the fold’. There’s minority bashing and majoritarian bullying. There’s the looming shadow of the Naxal ‘menace’, the region being a hotbed of unrest, with anyone opposing the state running the risk of being hauled up as a Maoist. As the beleaguered teacher says in court, “To the school and the church, I am an atheist and an apostate. To the police, a Maoist.”

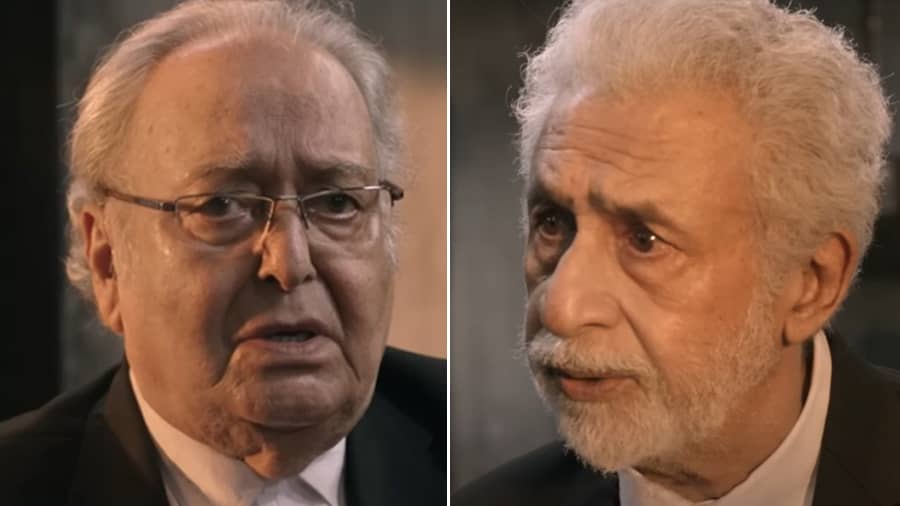

Naseeruddin and Soumitra: courtroom as masterclass in acting

What gives the adaptation its heft is the way it incorporates these diverse strands into a debate on man’s right to think. “The right to think is on trial here,” says Anton D’Souza (Naseeruddin Shah), the counsel for the defence. “A man is on trial,” argues Reverend Basanta Chatterjee (Soumitra Chatterjee), on behalf of the prosecution. “A thinking man,” comes the immediate riposte.

With two stalwarts like Naseeruddin Shah and Soumitra Chatterjee feeding off each other, the courtroom becomes a site for a masterclass in acting. The former is in his element and pitch-perfect as the disillusioned lawyer who finds a new cause to fight for (just savour his wry, almost resigned smile as Basanta mentions him having disappeared from the legal scene). Soumitra Chatterjee, in his final completed film appearance, has a much more complex role to essay as a legal luminary who bats for faith over science, who is fair game to be labelled a bigot and an opportunist, and who discovers too late that he has been manipulated.

‘Verbosity is normal in a courtroom drama’

If the film delivers less than what it promises and its premise, it is because of its propensity to become declamatory. It almost seems like it’s too aware of the importance of what it is saying, almost messianic in its zeal. Mitra reasons, “If you visit any courtroom in our country, you will find none of them are silent. Lawyers shout at the top of their voice and plead. And when they plead to the bench, they only have words to drive home their arguments. How can you make a movie on court proceedings without dialogue? Verbosity is normal in a courtroom drama.”

The background score also sounds overwrought. A particular sequence involving an argument between the two lawyers gets drowned in a chorus of gratuitous ‘hallelujahs’. Which is surprising given the nuanced score that underpinned what I believe is Mitra’s best film, Chitrokar. Of course, the two films differ vastly in genres and tonality. A point that Mitra makes. “The music of the two films is of different types. In Chitrokar, music was used to underline the theme’s contemplative nature, but in A Holy Conspiracy it is a means to excite the audience. But I think I have used fewer music tracks than one would tend to use. Except for one or two loud tracks, others are very mellow, and soft.”

And at 143 minutes, it’s probably half-an-hour too long with a few sequences – Kunal’s love interest and the local pastor’s daughter Reshmi marching up to meet Chatterjee and the conversation that follows with the reverend’s wife, the almost frivolous attitude of the journalist (played by Koushik Sen) at times – that stick out like a sore thumb and render the screenplay patchy. “Those scenes are there to give fullness to the characters you mention,” the director says. “I think every character in a film needs to be fleshed out for the more discerning viewers who watch a movie without a watch on their wrist.”

‘My objective was to have a discourse on the present situation of our country’

Also, it would have been interesting to see the film address an issue – and we have seen too many of these to recount – that resonates more with the general public than the one pertaining to evolution and creationism which is rather esoteric in the Indian context. To that Saibal Mitra says, “The issue in the movie is different. The discourse or debate on creation and evolution is just the face of the movie. It’s there on the surface. I never wanted to make a movie on a specific incident. My objective was to have a discourse on the present situation of our country where you can link all the issues you mention.”

‘It’s a conspiracy under the cover of religious holiness’

Connected to this is the fact that Christians are a minuscule percentage here (though they and the tribals are being persecuted too). One wonders if issues used to persecute Muslims would have given the film more immediacy and potency. “It’s a MacGuffin in the Hitchcockian sense,” Mitra says. “It’s a conspiracy under the cover of religious holiness. You can call it a calligraphist movie to understand its sub-image. You can replace Christians with any minority group here. Every minority community is under attack by the upper-class majority community of India. Their Hindutva politics has a religious layer that outwardly looks holy. The conspiracy is inherent in it. This is why the name of the movie is A Holy Conspiracy.”

‘Censor board said they would request everybody to watch it’

Given the explicit nature of the discourse in the film, were there apprehensions about running afoul of extra-constitutional censors? Or did making it in English render it safe by limiting its reach? Were there any issues with the CBFC regarding conversations that cut close to the bone?

“I was very much aware,” the filmmaker admits. “I wanted to name the movie I Am Not a Hindu, taking off on what Kunal Joseph Baske, the tribal teacher, says in the film, asserting his right to his own identity. Someone advised me not to be so explicit. But my experience with the censor board was different. The members of the board told me that they would request everybody to watch the movie. They were so moved after the screening. And obviously, I felt relieved.”

A lesson in intelligent adaptation for Laal Singh Chaddha

In spite of its rough edges, A Holy Conspiracy is an important film, a bold film that dares to go where most filmmakers today wouldn’t. It is an intensely political film, an almost lost genre today. How important is it for a filmmaker to be political? Particularly at a time when that is fraught with danger. Mitra says, “Cinema can be musical, mythological, or political. It’s not a big deal. But having said that it is also true that all my films to date have political layers. The film that I made before A Holy Conspiracy, titled Takhon Kuasa Chhilo (Blind in the Mist) dealt with the political scenario in Bengal. The danger of making such movies that you refer to is I think a fear that exists in our minds. I never target any party or group in my film. I just express my thoughts about my surroundings. I am not a political activist in any way. But I cannot detach myself from the immediate world I live in.”

Coming as it does from the barren landscape of Bengali cinema, it’s doubly rewarding. And for those going gaga over Laal Singh Chaddha’s reworking of Forrest Gump, here’s a lesson in intelligent adaptation, making an almost century-old case in another land relevant to contemporary Indian society.

‘Soumitra-da was awed to see Naseer-ji perform and…’

Then there’s Naseeruddin Shah and Soumitra Chatterjee facing off together for the first and only time. How did the casting coup happen? “It was a natural process. I just found them suitable for the characters I wanted to portray in the movie. I came to know about their respect for each other while shooting the film. Both helped each other in many ways. Soumitra-da was awed to see Naseer-ji perform and it was the same with Naseer-ji who came forward to help an ailing Soumitra-da in every shot. It was an experience of a lifetime for all of us, watching two giants perform in front of my camera on the shooting floor. It’s difficult to share something like this in words. It will stay with us as long as we live. It has happened only once in the history of Indian cinema. It won’t happen again.”

For that alone Saibal Mitra deserves our gratitude and that alone will ensure the film’s place in posterity.

A film on Byomkesh, a surreal meditative tale on art and corruption, a political tract. What next? “I am not sure but maybe a science fantasy… that too with a political undertone,” smiles the filmmaker.

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is a film and music buff, editor, publisher, film critic and writer.