Recently, the Museum of Cartoon Art was inaugurated at Savitribai Phule Pune University and an art gallery, also in Pune, by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in memory of the legendary cartoonist R.K. Laxman. A little ironic given that political cartoons have almost entirely disappeared from our dailies and magazines.

Cartoons are a barometer of democracy, says cartoonist Sandeep Adhwaryu, who is based in New Delhi. “They are integral to society and reflect the times we live in,” he adds. If that is so, the barometer is showing unnatural weather conditions.

In September 2012, cartoonist Aseem Trivedi was arrested on sedition charges for a series that satirised widespread corruption in India. One of his cartoons showed the Parliament building as a lavatory buzzing with flies. The website hosting the series was blocked. Trivedi spent three years in court fighting his case as well as challenging the validity of the IT Act’s controversial Section 66A, which imposes up to three years imprisonment for sharing “offensive” messages online. At the time, the BJP criticised the move. The party spokesperson Shahnawaz Hussain said, “You are in power, that does not mean you impose an undeclared Emergency in the country.”

It has been 10 years since Trivedi’s arrest. In the last five years, more cartoonists have either lost column space or favour with this political party or that. Among the better known cases are those of Delhi-based Satish Acharya and Mumbai-based Manjul.

In 2018, Acharya’s cartoon of Prime Minister Modi in the grip of China was dropped. In 2021, senior lawyer Prashant Bhushan shared one of Manjul’s cartoons showing India’s slow and inadequate response to the pandemic. In turn, Bhushan received a notification from the social media platform, Twitter, informing him that he had “violated the law(s) of India”. The consequences were much harsher for Manjul. His contract — with the media house he worked for — was terminated and he too received the “violated” mail from Twitter at the request of the central government.

This time the Congress condemned the BJP’s “unprecedented highhandedness”. Their spokesperson Sachin Sawant said, “One can definitely say that an undeclared Emergency is nearing...”

Sentu, who, like many cartoonists, goes by just one name, began contributing political cartoons to Bengali papers a quarter century ago. The Calcutta-based cartoonist regrets his inability to critique any political leader in power today despite the wealth of material at his fingertips. He says, “I got away with lampooning many Leftist leaders. That would not be the case today. I would probably get beaten up.”

His friends in the TMC will probably apologise to him personally after their goons beat him up, he says with a laugh. But he is determined to still point out ills in society. “If there is no water supply, I will obviously sketch it even if I do not lay the blame on anybody,” says Sentu.

Satish Acharya, who continued to draw cartoons even after his run-in with the authorities, says, “I kept losing clients, as I refused to dilute my cartoons.” His recent work on Covid-19 mismanagement can only be seen online. Sentu agrees that while cartoons barely get published, they are flooding the Internet. Even Manjul, who has been a cartoonist these 30 years, continues to do political cartoons but in his own space, namely his social media accounts. His platform switch, of course, came at a cost, literally and otherwise.

Cartoonist Surendra, who recently retired from a leading Chennai-based news daily, says he knows of “brilliant cartoonist friends” who have lost clients and are finding it difficult to survive.

Recently, the Museum of Cartoon Art was inaugurated at Savitribai Phule Pune University and an art gallery, also in Pune, by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in memory of the legendary cartoonist R.K. Laxman. A little ironic given that political cartoons have almost entirely disappeared from our dailies and magazines.

Cartoons are a barometer of democracy, says cartoonist Sandeep Adhwaryu, who is based in New Delhi. “They are integral to society and reflect the times we live in,” he adds. If that is so, the barometer is showing unnatural weather conditions.

In September 2012, cartoonist Aseem Trivedi was arrested on sedition charges for a series that satirised widespread corruption in India. One of his cartoons showed the Parliament building as a lavatory buzzing with flies. The website hosting the series was blocked. Trivedi spent three years in court fighting his case as well as challenging the validity of the IT Act’s controversial Section 66A, which imposes up to three years imprisonment for sharing “offensive” messages online. At the time, the BJP criticised the move. The party spokesperson Shahnawaz Hussain said, “You are in power, that does not mean you impose an undeclared Emergency in the country.”

It has been 10 years since Trivedi’s arrest. In the last five years, more cartoonists have either lost column space or favour with this political party or that. Among the better known cases are those of Delhi-based Satish Acharya and Mumbai-based Manjul.

In 2018, Acharya’s cartoon of Prime Minister Modi in the grip of China was dropped. In 2021, senior lawyer Prashant Bhushan shared one of Manjul’s cartoons showing India’s slow and inadequate response to the pandemic. In turn, Bhushan received a notification from the social media platform, Twitter, informing him that he had “violated the law(s) of India”. The consequences were much harsher for Manjul. His contract — with the media house he worked for — was terminated and he too received the “violated” mail from Twitter at the request of the central government.

This time the Congress condemned the BJP’s “unprecedented highhandedness”. Their spokesperson Sachin Sawant said, “One can definitely say that an undeclared Emergency is nearing...”

Sentu, who, like many cartoonists, goes by just one name, began contributing political cartoons to Bengali papers a quarter century ago. The Calcutta-based cartoonist regrets his inability to critique any political leader in power today despite the wealth of material at his fingertips. He says, “I got away with lampooning many Leftist leaders. That would not be the case today. I would probably get beaten up.”

His friends in the TMC will probably apologise to him personally after their goons beat him up, he says with a laugh. But he is determined to still point out ills in society. “If there is no water supply, I will obviously sketch it even if I do not lay the blame on anybody,” says Sentu.

Satish Acharya, who continued to draw cartoons even after his run-in with the authorities, says, “I kept losing clients, as I refused to dilute my cartoons.” His recent work on Covid-19 mismanagement can only be seen online. Sentu agrees that while cartoons barely get published, they are flooding the Internet. Even Manjul, who has been a cartoonist these 30 years, continues to do political cartoons but in his own space, namely his social media accounts. His platform switch, of course, came at a cost, literally and otherwise.

Cartoonist Surendra, who recently retired from a leading Chennai-based news daily, says he knows of “brilliant cartoonist friends” who have lost clients and are finding it difficult to survive.

Manjul tells The Telegraph how, even if he now draws a cartoon supporting the Prime Minister, it is taken for criticism and he gets trolled. He says, “I have been branded as anti-government and nobody will take a look at the cartoon. Without understanding it they will just start criticising.”

Satish has a diagnosis for this condition. He says, “Ideally, every citizen should question the government regularly. But when people change their role to defending the government, you can’t expect them to laugh at a cartoon ridiculing it.” This means whatever political cartoons exist even now tiptoe around an unwritten state censorship and has gone through the sieve of self-censorship.

“What is the use of drawing cartoons that cannot be printed,” asks Sentu, who is considering drawing comic strips for children.

The colonials, lampooning whom Indian cartooning came of age, believed the “natives” did not have a sense of humour. Charles Dickens had written in 1862, when there were discussions about bringing the British satirical magazine Punch to India: “The idea seems unpromising. A professed jest must surely be out of place among a people who have but little turn for comedy. The Asiatic temperament is solemn, and finds no enjoyment in fun for its own sake.”

That might be largely true, but it is also sad and strange given that India had its own indigenous satirical tradition. In an essay titled “Before the political cartoonist, there was the Vidusaka: a case for an indigenous comic tradition”, Snehal P. Sanathanan and Vinod Balakrishnan write of the presence of caricature as a manifestation of hasya in Indian temple art of 200 AD. They cite Mughal art, which was characterised by “striking caricature likenesses” and Kalighat paintings of 19th century Bengal, which employed “wilful satire and deliberate caricature”.

Indians took to Punch. Thereafter, with the burgeoning print culture political cartooning in print media flourished. The Oudh Punch, Hindu Punch, The Delhi Sketchbook, Matvala, Basantak, The Indian Charivari, all published cartoons. Cartooning in India began with the British making a commentary on the natives, and then in the first half of the 20th century it became an expression of nationalism in Indian newspapers. Post Independence, cartoons did the job of the Opposition.

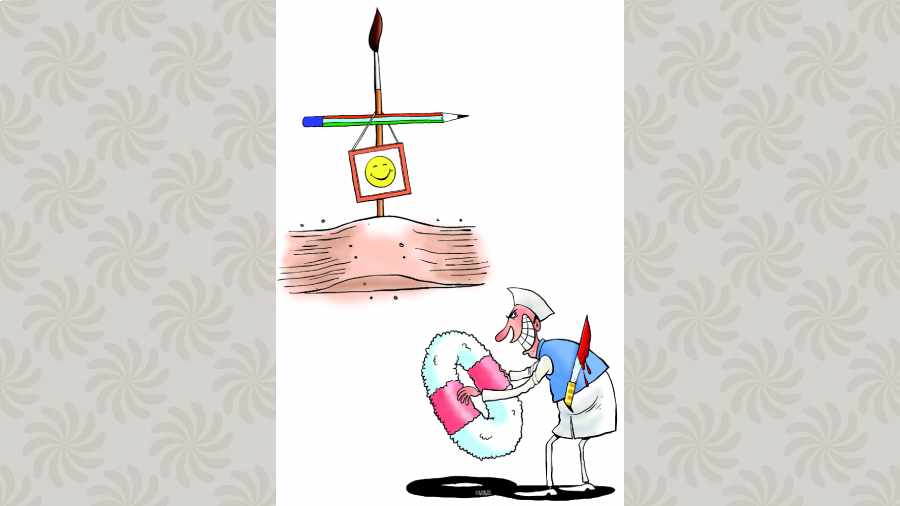

Anandabazar Patrika published its first cartoon exactly a hundred years ago on March 18, 1922. It called for the resignation of Lord Montague. In Bengali, resignation translates as padatyag, which literally means leaving behind your post but pad also means legs.

The cartoon showed Montague leaving behind his legs.