" Panje ki nishaan dikhta hai (We can see pug marks),” whispered our guide-cum-driver Mohitji, keeping one eye on the road in front, actually a dried up monsoon river bed, strewn with smooth and rounded boulders, the second eye scanning the trees above for avian life, two hands strongly grasping the steering wheel, and the proverbial third eye focused on the soft sandy ground opposite his driving seat, while the rest of us barely managed to keep our cameras and wits together bouncing up and down on passenger seats as the hoodless Gypsy went off-road.

When the Gypsy stopped, we could see clearly the pug marks of a tiger beside our vehicle. I had managed to pick up some jargon and timidly ventured, “Kata hua hai (Has it been crossed)?” meaning whether the pug mark had been cut by tyre marks indicating that the former may not be recent.

Sujit Chakrabarty, a wildlife expert and coordinator of our Jim Corbett National Park safari, explained to us patiently the reason for Mohit’s excitement: “Look Subirda, when we went in this direction just now, the footprints were absent and also there are pug marks on top of our tyre markings so the tiger definitely passed a few minutes after us, but between her passing (by the way, the pug marks were identified to be of a tigress) and our doubling back another car has also crossed the same area.” We had missed the lady by a whisker, no pun intended. This is only a part of the process of tracking Panthera tigris tigris, that is, the royal Bengal tiger!

A male sambar enjoying a salt lick

The most common question on the lips of every forest guide and Corbett veteran was, “Call sunaai diya?” One has to filter out the alarm calls of the preys of the tiger from the continuous chirping of birds and the monotonous sound of the Gypsy. If the call was that of a deer, the next task was to identify whether it came from spotted deer (chitral or chital harin), barking deer (sonar or golden harin), or sambar (large deer like nilgai).

For the chital, unless the calls were repeated a number of times, it might not be a true alarm call because the chitals are a nervous lot and can easily become animated. On the other hand, the alarm call of a sambar meant serious business. But the most reliable were the calls of langur monkeys who could keep an eye from above.

Then there are calls coming from peafowls as well. Remember that timing is of the essence and after the mental arithmetic one needs to drive like mad in the correct direction because many a time the tiger is visible only for a fleeting moment as he or she comes out in the clearing.

Besides Sujit, there are three of us: Abhijit, a birding specialist and expert in astrophotography; Nibedita and myself, both of us being wildlife enthusiasts. Sujit had planned a four-night-five-day Corbett tour in which we managed to cram 10 safaris, each of four-hour duration, 7am-11am in the morning and 2pm-6pm in the afternoon.

Corbett is one of the very few remaining national parks where night stay deep inside the forest is still allowed. All the forest rest houses (FRH) were surrounded by electrified fences, mostly to stave off elephants. Apart from experiencing the night inside the dark jungle full of mysterious sounds and sometimes seeing only a pair of eyes illuminated by the faint light of the FRH, being inside the core forest saves the long drive from the main forest entrance gates.

We had planned to stay two nights at the Dhikala zone FRH, the hottest of the tiger hotspots, and one night each at Gairal FRH, also in the Dhikala zone, and the last night at Malani FRH in Bijrani zone. The Uttarakhand government has adopted the policy that three consecutive night bookings in any particular FRH will not be allowed and rebooking the same FRH can be done only after a 15-day gap. Also, at any zone, during safari time, at most 25 vehicles with tourists are allowed to stay inside.

Established around 1936, Hailey National Park is the precursor of the present day Jim Corbett National Park. Covering about 520sq km in the Nainital district of Uttarakhand, Corbett holds the proud distinction of being the place where the Project Tiger was launched in 1973. Undoubtedly, it happens to be one of the oldest and best-known reserved forests in India.

Corbett offers everything a nature lover can ask for: crystal clear Ramganga river flowing throughout, vast grassland areas, pristine dense forests with the backdrop of the Shivalik range of the Lesser Himalayan Chain. The forest tours are very much tiger centric and the guides and visitors are always exchanging notes about tiger sightings. The guides are connected to each other by mobile phones now and get updates in the few places inside the forest where mobile signals are available.

Indeed it is a cliche, especially in a tiger reserve, to say that the forest has to be experienced in its entirety and the tiger is only a cog in the ecosystem wheel and so on. But after having your fill of tiger sighting (if that is possible!), you can relax and take in the beauty of Corbett.

(Left to right) A family of foxes; A langoor in the evening

The varied fauna is bewildering. During our short stay, apart from large groups of chital, hog deer, barking deer and sambar, we saw wild boars, a Himalayan jackal family, both gharials and muggers, and short-clawed Himalayan otters, among others.

Elephants crossing a forest path

The majestic elephants are a common feature, sometimes a single one munching away peacefully or in a small family group with the calf towing along. Close to the Malani FRH a jackal was desperately trying to get the better of a large sambar leg it had probably stolen from a satiated tiger.

A quick way to get a feel of Dhikala is to avail of the day safari on a Canter, a large bus with open windows that can only travel in prescribed zones inside the forest. Generally the Gypsy guides and us forest dwelling tourists treat the Canter-wallahs, driver and day visitors alike, in a patronising tone and feel that the big buses full of amateurs will scare away the animals.

As we kept vigil inside the jungle a Canter came with the people eagerly asking us about sightings. We curtly replied in the negative and moved away thinking that chances of a tiger near the Canter is very bleak. After about an hour or so to our utter disbelief we came to know that the Canter people in that same spot had seen not one but four tigers, a mother with three sub-adult cubs! Mohit was furious about the betrayal of the big herd of chitals grazing nearby at that time for not providing us with the alarm calls.

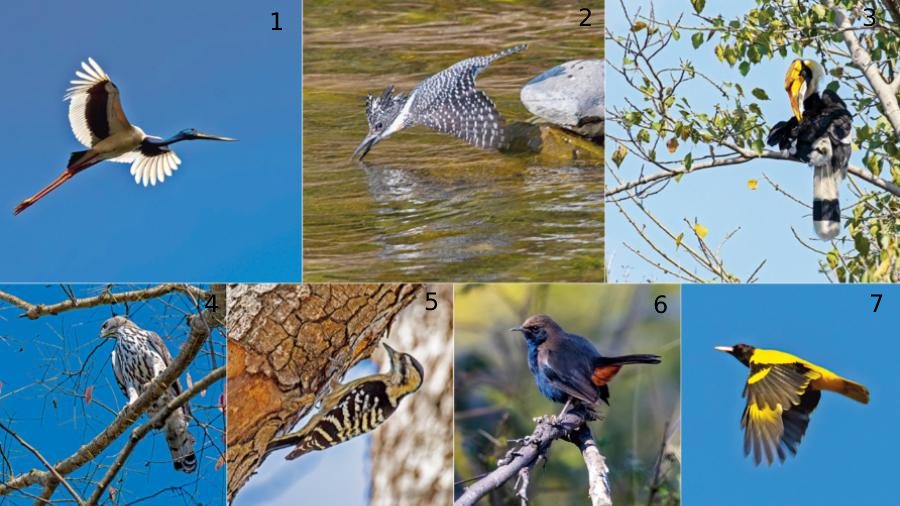

1. Black necked stork 2. Crested kingfisher; 3. Great Indian hornbill; 4. Hawk eagle (juvenile) 5. Pygmy woodpecker; 6. Indian Robin; 7. Black hooded oriole

Birdwatcher’s paradise

The sheer variety of birds is another strong point of Corbett. Suddenly a group of scarlet minivets fly away in a bright splash of red against the azure sky. The vociferous plum-headed and Alexandrine parakeets are everywhere. An elegant black-necked stork entertained us with a ballet show on the Ramganga riverbed. We could spot the nesting hole of a giant crested kingfisher that was diving in the nearby river. The colourful common kingfisher was busy softening out the small fish by repeatedly hitting it on the hard rock.

In the Dhikala FRH jumbo lenses were targeting a pair of brown-headed pygmy woodpeckers, high up in a tree. A pair of highly territorial red-headed lapwings started to warn me menacingly as I inadvertently moved close to its nest.

There were all kind of raptors; the serpent eagle waiting patiently atop a tree overlooking Ramganga river, a Pallas’s eagle drying off the night dew in the morning sun, grey-headed fish eagles guarding their nests, changeable hawk eagle watching over the vast grassland from high above, a ruby-eyed beautiful dark-shouldered kite taking off and the ghostly outline of an owl at night in Malani FRH.

A large group of Himalayan griffon vultures had congregated in a sheer cliff in the Jhirna zone and were squabbling for the best spot. And then there were hornbills. We could spot a group of grey hornbills and great hornbills flying above us with their clownish features. I wistfully thought how nice it would have been if we could get a clear shot of the great hornbill perched atop a tree.

Tyger, tyger...

In Bijrani zone, after about two hours of a morning safari we had just finished our takeaway bread-omelette breakfast and were leisurely pouring the morning cuppa when suddenly Mohit vaulted on the driver’s seat and reversed the Gypsy in full swing with us splashing the garam cha on our co-passengers.

We roared in just in time to watch, together with a handful of vehicles, a tigress cross the open road nonchalantly in the fading evening light. Sujit was pretty satisfied because sightings in Bijrani have become rare. “Mohit bhai, ye kya Paharwali lagta hai?” “I will have to check the headshot for markings.”

A quick way to identify tigers is through their distinctive stripes, especially in the facial region. Nowadays software can do the job accurately. Tigers all over India are formally identified by a number tag but the forest people lovingly refer to them with names that reflect their territorial zone, their behaviour and so on.

Paharwali rules the hilly region, Sharmili is the shy one and Pandit is the wise and mature male. It is my impression that males are more shy compared to females although a tigress with cubs becomes highly secretive since she has to keep the cubs away from other mammals including rival male tigers, each eager to spread its own lineage and not tolerating competition. The female tiger will mate with another male only when her children have grown and moved away or are killed during infancy.

As a rule tiger sighting is easier in Dhikala since here they have grown used to tourists and there are long open riverbeds and grasslands that give ample time to watch the beautiful animals in their full glory. We came across a lazy tiger early in the morning that was resting after a large meal of a deer that it had caught at night.

We could also witness the rare scene of a prey and predator together, peeping out from the dense greenery. Two sambars were also close by, alert but not unduly alarmed. Suddenly the tiger yawned, stretched and crept noiselessly close to the two deer. We were separated from the whole scene by a shallow dry ditch, not more than 15m-20m away. Suddenly there was a commotion with a muted roar and a shriek from the deer; one of them ran away along the ditch but the other in a desperate bid to cross over the ditch nearly climbed on to our Gypsy!

In the Jhirna zone, the forest was awash with the golden afternoon sun. A large langur family was resting on a tree, the older ones grooming each other and eating the tidbits discovered in the process, while keeping an eye on the playful juveniles and infants. A newborn baby was suckling. I was startled to see the exact similarity between newborn human and langur babies!

Suddenly a great hullabaloo on a tall tree caught our attention. A group of about four-five grey hornbills and three great hornbills had just arrived. They were partially hidden by the tree canopy but we could see one great hornbill delicately putting a berry in the beak of a young one, their gigantic beaks gently touching each other. All of a sudden the birds started to fly off but as if hearing our silent prayer, one great hornbill came clearly into view and unhurriedly started to preen himself while performing impossible-looking acrobatics.

Like other Corbett regulars, after quite a few sightings of tigers indulging in various activities such as crossing the blue waters of panoramic Ramganga river, resting near the swimming pool (local name for a small lake) in close proximity of a spotted deer or taking it easy after a meal, we were having a feeling of deja vu and wanted something new.

Instead of jockeying with other tourists for a better view, what we desired was the ultimate happiness of an exclusive tiger sighting with only us being present. Our tour was coming to an end and Sujit had already warned us that in the secluded Jhirna zone tiger sightings are very rare. We had planned to conclude the trip with a quick morning safari on the way out when suddenly there were a number of nearby loud alarm calls. All at once we forgot about return flights and switched to tiger mode! After a quick mental calculation Mohit zeroed in on the best possible spot within a dense forest of tall sal trees on all sides of us and cut off the motor.

In the mysterious light and shade Chukha Paani materialised, noiselessly walking over the crumbling dead leaves and just like a dream sequence, melted away among the trees, our very own tigress. Finally we were leaving Corbett , happy with our parting gift and with the haunting words of Sujit: “You can get out of Corbett but you will never take Corbett out of you!”

Pictures by the author

The author is a professor and wildlife enthusiast