In a dingy corner of an ancient post office in central Calcutta, you will find Mithu Paul poring over the screen of a portly personal computer. She’s a senior clerk and takes care of fixed deposits, savings accounts, monthly income schemes and the like. It’s the dreaded first week of a month, when seniors queue up in front of two counters from early in the morning to collect monthly interest on their deposits. Paul disburses the cash, never looks hassled, not even when someone or the other hollers “taratari korun”, or hurry up!, from the back of the line. All through she is interrupted by junior colleagues who keep asking her for tips for this or that. Paul responds to each query while counting the money, scribbles something in the ledger. She also remembers to smile at the elders while handing over the cash.

Paul is not the typical kerani or clerk, but she belongs to that breed of professionals whom we have learnt to unsee for two centuries, though without their services entire governments could crumble and whole systems could grind to a halt. Come to think of it, even the much-invoked Chitragupta is a very senior clerk.

The Bengali word kerani derives from the Sanskrit root karanik, meaning a person who keeps notes and maintains documents, usually in an office. The Persian equivalent used in Mughal India and in the early British period was munshi. It was used for writers, secretaries and even those who taught the “native languages” to the sahibs. Queen Victoria’s favourite Indian attendant Mohammed Abdul Karim was known as “the Munshi” in the British royal family.

But in the later period of the Raj, the clerk lost his exalted status. Colonial policy turned him — this was a male-only profession for the longest time — into a keeper and mover of files. In Bengal, the clerk came to epitomise that person at the other end of the intellectual spectrum, the person no one ever wanted to become.

You might have heard of the maacchimara kerani. The story goes that a clerk was asked to make a “true copy” of a document by his boss. He toiled through the day and then discovered a dead fly stuck to the last page of the ledger. To make his duplicate a “true copy” he swatted a fly and pasted it by way of final touch. Maacchi is housefly in Bengali. Today, the phrase maacchimara kerani is used to suggest a person with no great responsibility.

The other descriptor that is used in connection with the kerani is chhaposha. It suggests someone ordinary, and the in-built smallness, pity and cruel humour is untranslatable. The 1952 Bengali film Keranir Jibon depicted the life and death of clerk Bidhubhushan, who was employed in a mercantile firm in Calcutta. Bidhubhushan struggles to feed his family and fund his children’s education. After his eldest son dies, he suffers a heart attack and dies in his rented house. The tragic story, however, has a silver lining in Rabin, a junior clerk who stands up to his villainous boss. He inspires fellow clerks to protest against injustice. His firm stand gives a hint of the militant trade unionism that would gradually spread in government offices, banks, post offices and private firms during the Left Front era.

Like Paul, Subrata Bhowmick is proof that there are clerks and there are clerks well beyond the stereotype. Nearly 40 years ago, fresh out of college, Bhowmick joined what was then the Bharat Overseas Bank. He went on to become a union leader fighting against the indiscriminate transfer of employees. By way of a rap, he too was transferred to Gorakhpur in Uttar Pradesh. Bhowmick challenged the decision in Calcutta High Court and went on leave without pay to fight a long-drawn court case. Today, though, the 65-year-old thinks it is foolhardy to fight against the system. He says, “Such fights have ruined our work culture.”

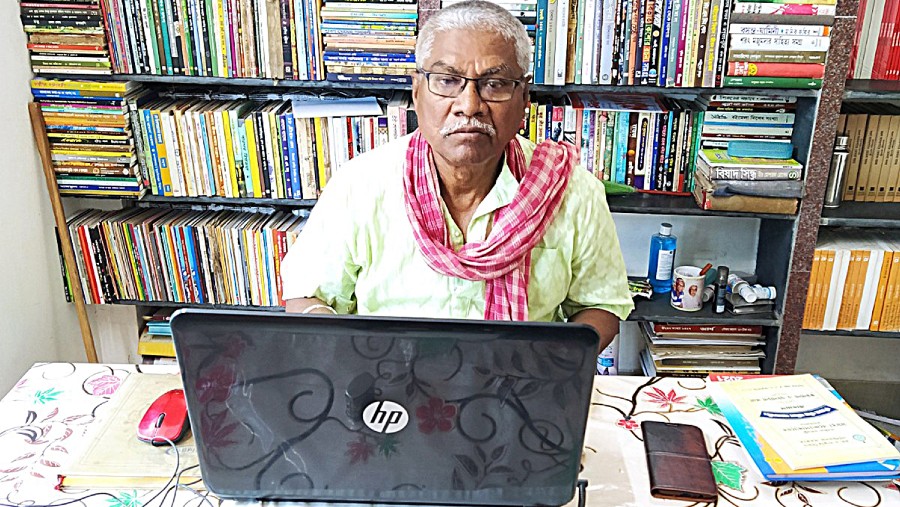

Writer Tapan Bandyopadhyay retired as the director of culture of the West Bengal government in 2007. But before he joined the state service, he was a clerk in a nationalised bank in Calcutta, and this despite his firstclass in BSc mathematics. He says, “I used to handle bank ledgers. The job was secure and I had a parallel life as a poet and writer, still I suffered from an intense feeling of inferiority or inadequacy.”

It was this feeling that motivated him to crack the state civil service exams. Subsequently, as a bureaucrat, he was posted in various districts of Bengal, including Calcutta. He also did a long stint in The Writers’ Buildings, erstwhile hub of Bengal administration. For those who don’t know or forgot, Writers’ had been conceived by British colonialists as the residence of writers or clerks of the East India Company.

Bandyopadhyay has written two books — Haripada Keranir Diary and Boss Brittanta. He says, “The general perception is that clerks are lazy, will gossip and bunk work, but my experience of working with them is not bad. One out of five I encountered would have fitted the description of a typical idle kerani, but most were quite efficient. A good clerk is the pivot of an office.”

Bandyopadhyay tells the story of one clerk at Writers’ who wrote excellent English and completed his PhD while working in the culture department. “I had also come across an accomplished sitarist working as an LDC (lower division clerk),” he adds.

Subrata Goswami had been a promising footballer and a classical singer when he appeared for the clerkship exam in 1979, but today, he is happy to be a clerk. He has worked in various state government offices for over four decades, organised theatre festivals, gaan melas and jatra utsavs and travelled across the country on the job. “I had a fulfilling career across various departments,” he says. “But my greatest satisfaction came from the fact that I have been able to help dozens of fellow workers organise critical documents required during their pension settlement. This was not part of my job, but I liked helping out people,” he adds.

Paul too prefers her clerk’s job. She says it allows her to support her sons’ education without distraction; a promotion to a senior position would have required her to be transferred to some district town. In her leisure hours, she sings. She says philosophically, “As a post office clerk, I draw inspiration from the dak runners of the British era. They risked their lives to deliver letters or messages across the wilderness. They knew it was a thankless job, but they kept on running.”