When I called up Manoranjan Byapari sometime end-February, he was busy with the launch of the English version of the first part of his semi-autobiographical Chandal Jiban trilogy, The Runaway Boy. He had been travelling in and out of Calcutta, attending book signing events and readers’ meets. In addition, as the chairman of the newly formed Dalit Sahitya Academy of Bengal, he was hopping from meeting to seminar as part of an effort to publish an anthology of works by writers from backward classes. In the meantime, there was also a low hum about him joining the Trinamul ahead of the West Bengal Assembly elections.

I finally met Byapari at his home in Khudirabad on the southern fringe of Calcutta. He came to the toto — e-rickshaw — stand to take me home. “The lanes are narrow, you would have had trouble locating the place on your own,” he said matter-of-factly as he walked ahead briskly, a stocky man dressed in a khadi kurta and frayed trousers. Coiled around his neck was a gamchha and on his face he wore a grimace.

The neighbourhood is dotted with huts. Byapari pointed to a row and said, “The area used to be full of bheries (fish ponds) owned by jotedars (feudal lords) in the early 1970s. Later, Left Front cadres grabbed these, filled them up and sold the plots to poor folks like me.” He told me that now there is electricity and water supply, but until recently the place was quite underdeveloped.

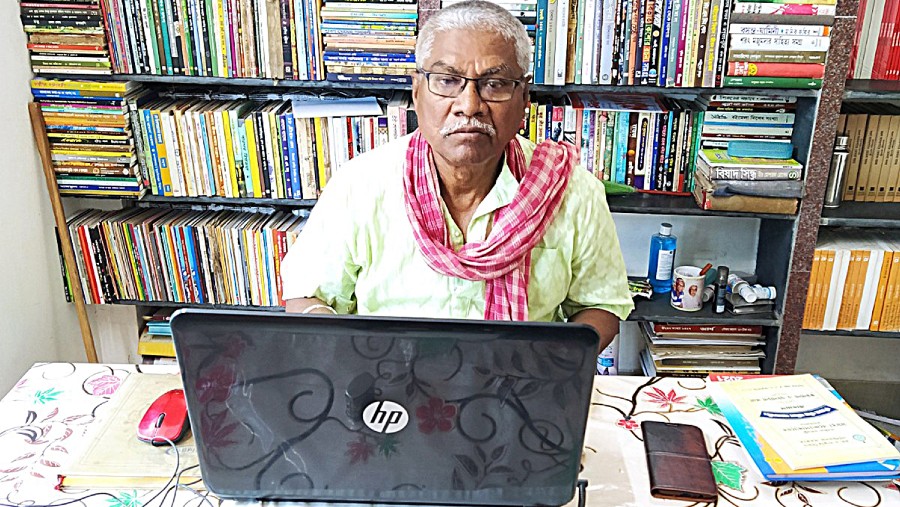

We settled down in Byapari’s study-cum-library. The bookshelves all lined with his new books, citations, medals, there were also a couple of photographs of him with distinguished personalities. While I browsed through the books, Byapari stood by the window and mixed khaini on his calloused palms. Without looking up he said, “I am the biggest seller of my own books. My young fans come to meet me here; I sign and sell these new books.” Indeed, gone are the days when Byapari had to self-publish his books and carry them around in search of buyers. Now, publishers of repute approach him routinely; they want to publish him. Two of his books are being translated from Bengali into English and 10 other Indian languages.

Byapari worked as a rickshaw-puller, a cook, a coolie, a chowkidar in a forest reserve, a daily-wager, and even a helper at a crematorium before he turned writer. He said to me jocularly, “Ami nijeke lekhowar boli — likhte likhte lekhowar. Jemon khelte khelte khelowar,” basically trying to convey through wordplay that he is a self-taught writer who never had the advantage of a formal education.

He learnt to write with a stick on the dirty prison floor when he was jailed in the early 1970s at the peak of the Naxalite movement. For the longest time, he cooked mid-day meals at a school for the deaf and blind, until he got a job in a government library last year. And all these life experiences have been channelised into his writing — 13 novels, over a 100 short stories and some works of non-fiction, all in Bengali.

Speaking of writing, among the framed photographs on his bookshelves is one of the late writer-activist, and his mentor, Mahasweta Devi. Byapari’s first encounter with the writer while ferrying her in a rickshaw is the stuff of urban legend. Intrigued by his inquisitiveness and love for literature, Mahasweta Devi apparently commissioned and published Byapari’s first piece titled Ami Rickshaw Chalai (I Pull a Rickshaw) for her magazine Bartika. Since then, Byapari has never had to look back.

There is another photograph that caught my eye, that of him with chief minister Mamata Banerjee at a public meeting.

At the time of the interview, Byapari had not joined the Trinamul. So when I asked him if he was now pro-establishment and part of the government, he replied, “She (Mamata) is the one who recognised Dalit literature as part of Bengali literature. She has given me an opportunity [as the chairman of the Dalit Sahitya Academy] to showcase that we Dalits have been producing quality work. Now we can show people that unlike upper-caste writers, we write about our people with empathy; we don’t shower sympathy nor shed crocodile tears.”

That day he didn’t divulge anything about a more active role in the impending elections, but he spoke about how one should stand by Mamata in order to defeat the BJP, which he called “a violent and anti-people party, all out to grab Bengal”. He said, “I am not canvassing for the Trinamul. Just walk down this lane and ask people how they have suffered from lack of drinking water, electricity and metalled roads.”

I remembered his short story Nisshobdo Baan or The Silent Arrow from 2010, which is about a rickshaw-puller who is bribed by the CPI(M) and the Trinamul ahead of the elections. Bhashan, sick of plying his rickshaw through the muddy and waterlogged roads of Khudirabad, decides to put a stamp against both symbols in his ballot paper and waste his vote. It is his way of registering a protest. Most of the stories in Byapari’s latest collection make strong political statements. The story Poriborton Chai is about a garbage collector who learns that nothing really changes for the marginalised even if political regimes change. And Tolabaaj is about political goons and the police ganging up to extort or collect tola from the common man. Nyata is about villagers being polarised along religious lines by a Right-wing organisation.

Three years ago, I had met Byapari for the first time at a conference on Dalit literature. I had been struck by his strong political views, especially about all shades of Communists, his association with Shankar Guha Niyogi (the founder of Chhattisgarh Mukti Morcha, a trade union in central India) and his strong views about the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). Three years later, his political views remain unchanged but have become more hardened, more incisive. He spoke of how the CPI(M) came to power with the support of industrial workers, small farmers and refugees from East Pakistan, but deceived all of them. “We Dalits can never forget the massacre of refugees in Marichjhapi,” said Byapari.

According to him, the majority of Communist leaders in Bengal were actually god-fearing upper-caste representatives of the society. He said, “Witch burning in tribal societies and even instances of untouchability in remote villages sometimes hit headlines during the Left Front rule.” And according to him the Left’s failure to break caste barriers and irrational mindsets of people helped the RSS carry on its polarising mission. “The RSS has been spreading its tentacles secretly through different fringe organisations in the state for several decades. They even managed to plant Trojan horses in leading political parties, including the Left. Now that the BJP is in power, these leaders are revealing their true colours and switching parties openly.” He added, “Hate for the marginalised and Dalits is in their DNA. They want to throw out the Constitution and establish Manuvad, wherein Dalits will be treated as slaves.”

But what about the Trinamul? What about Mamata? Why couldn’t she stop the BJP juggernaut? Said Byapari, “Frankly, I had next to no expectations from this government in the beginning since the Trinamul is also a Right-wing party. But, surprisingly, it has done a lot for a large number of people — its development schemes have reached many. She has tried her best to reach out to the Dalits and the underdogs.” Byapari, however, believes the chief minister should have been strict with corrupt party workers such as Suvendu Adhikari and thrown them out “long ago”.

A few days after this interview, the announcement happened. Byapari is to contest on a Trinamul ticket from Balagarh in Hooghly. When I called him the following night, he told me in politicalese,“ I’ve been writing about the trials and tribulations of people on the margins for decades, but haven’t been able to do anything beyond that. Now I am getting a chance to serve them.” On March 19, Byapari went to file his nomination at Chinsurah — the district headquarters; he pulled a rickshaw all the way to the district magistrate’s office. Party workers and supporters cheered him on saying, “Rickshaw ebar Bidhan Sabha-e… There will be a rickshawwala in the Vidhan Sabha.”

Têtevitae

1950s: Byapari is born in Turukhali in Barisal, now in Bangladesh. His parents migrate to a refugee camp in Bengal’s Bankura district soon after

1965: The family refuses to go to Dandakaranya, is shifted to Doltala refugee camp in South 24-Parganas

1969: He leaves the camp and starts travelling across the country — Assam, Delhi, Lucknow — doing odd jobs

1974: Is in Siliguri, close to Naxalbari, when the peasant uprising happens. Gets involved and is subsequently arrested and jailed for two years. Upon release, he settles down in Calcutta’s Jadavpur area, where he starts earning his living as a rickshaw-puller

1989: After a conflict with the Citu, leaves for Bastar. Meets labour leader Shankar Guha Niyogi there, at the Dalli Rajhara mines and becomes involved with the Chhattisgarh Mukti Morcha, a trade union led by Guha Niyogi

1990s: Returns to Jadavpur after Guha Niyogi’s assassination and starts plying the rickshaw once again. Meets Mahasweta Devi around this time

2000: Self-publishes his first book, Britter Sesh Parba; thereafter, writes many more

2020: In September, Mamata Banerjee announces the setting up of a Dalit Sahitya Academy in Bengal with him as its head

March 2021: Banerjee announces he has joined her party, Trinamul, and will be contesting Assembly elections from Balagarh