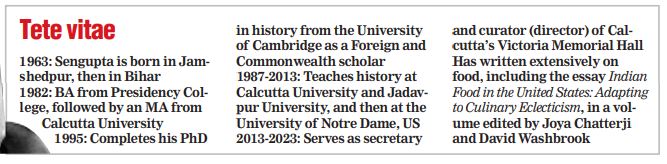

He straddles the worlds of art, academia, history and gastronomy with equal elan. The events organised by him as secretary and curator of Victoria Memorial Hall almost always ended on a sweet note with a perfect notun gur-er sandesh or a refreshing lebu sandesh, depending on what the season called for. In his office, one was invariably served a fine cup of Darjeeling tea and some crunchy nuts no matter how unsavoury the questions he might have had to field from the media. No wonder then that Jayanta Sengupta should retire with a book on food.

Hensheldarpan: Bangalir Handir Khobor is the food history of Bengal and refers to culinary traditions right from the Mangal-Kavya to the instant-pot generation.

Sengupta says, “The research interest grew out of my love of reading cookbooks. Around 2006-07, when I was working on the cultural politics of nationalism, I thought of food and cooking as possible windows to look at the interstices of family, community, nation, etc. I spoke on this in a couple of conferences in India, the UK and the US, and the questions they provoked inspired me to write one journal piece. And then one thing led to another.”

He talks about how in Bengali, we had classics on food and cooking but they lacked a serious examination of the relationship of food with questions of identity, community, nationalism and modernity. “This book is an attempt to bring this genre up to the level of current academic research with a light touch, so that it engages the general reader,” he tells The Telegraph.

The culture historian that he is, Sengupta begins from the beginning, and that is the bajaar or the marketplace. “It is a microcosm of the universe. You have the farmers selling greens from their fields on the fringes, you will have the fishmonger promising you a fresh catch from the pond, then there is fish transported all the way from Andhra Pradesh. A fishmonger will know from your tone whether you are from opar Bangla (East Bengal) or epar Bangla (West Bengal) and will sell you the fish you are craving for a modest profit.”

Sengupta continues, “It is not about getting the best at the cheapest price, rather it is about getting the best that is available at a price that doesn’t hurt you. And yet the quintessential Bangali babu will get a kick out of haggling with the farmer for a bunch of kalmi shaak (water spinach) priced at Rs 5.”

It is the marketplace and the henshel, or kitchen, that shapes the palate, according to Sengupta. He talks about how the kitchen wasn’t included in the domestic space through the first half of the colonial period (1757-1857). It was more of a service space inhabited by the servants.

After the revolt of 1857, a lot of British women came to India and set up home with British officers posted here. They established a home set-up where the kitchen was again described as a dirty space. It was only in the 19th century, when the educated Bengali under the influence of Western education took to a new way of living, that food and culinary skills became important.

This, of course, is true more for the affluent urban middle class with their retinue of servants. Satyajit Ray’s Charulata whiles away her afternoons reading Bankimchandra or embroidering handkerchiefs, having instructed the household helps to cook the fish with mustard paste.

The kitchen of the well-to-do Bengali in colonial India was a space integrally connected with an exalted idea of grihadharma, says Sengupta. Dozens of manuals were written in the late 19th and early 20th century on how the kitchen should be a clean and hygienic space with illustrations on how to store spices and other things.

Sengupta adds that educated women were required to have culinary skills as Pandit Ishan Chandra Basu writes in Nari Niti in 1884. Sengupta agrees that this was a form of patriarchy, but he also points to the fact that it is the entry of these women that transformed the kitchen space. Kitchens became spacious, well-lit and well-ventilated.

He devotes an entire chapter on the meat-eating habits of Bengalis and lends the lengthiest chapters on mishti. But the talking point of the book is perhaps the Ghoti-Bangal rivalry (West Bengal vs East Bengal) that spilled over from the football field to the kitchen. Says Sengupta, “Broadly speaking, the ‘rivalry’ was a product of the demographic reconfiguration brought about by Partition..., the long-drawn cultural ‘encounter’ and eventual assimilation all of that spawned.”

He remarks how all things cooked with posto or poppy came to be considered as typical of West Bengal, while certain recipes such as hilsa cooked with kalo jeere, kancha lonka (nigella seeds and green chillies) were considered to be legacy East Bengal culinary practice and something to rile and war on about.

In Ray’s Agantuk, the protagonist Manomohon Mitra, the lost and found uncle, says while examining a goyna bori, which is basically the name for dried lentil crisps shaped like a piece of jewellery, “Aharer eto bahar shudhu Bangladeshei shombhob... Such variety of food is to be found only in Bengal.”

So tuck away, and don’t let anyone have you believe that variety is unsavoury.