And the competition? “Since I was a newcomer, they did not allow me too many slots. But once I went in, I overstayed! I danced to my heart’s content, with my hip-length hair left open… The audience simply loved me.”

After Firpo’s, Miss Shefali reigned the Oberoi Grand for 17 years. Every anecdote, every relationship, every bend is perhaps worth the mention. She also acted in a few films, including Satyajit Ray’s Pratidwandi and Seemabaddha, and later joined theatre, egged on by Buroda (actor Tarun Kumar). She forged friendships with Ray, Uttam Kumar, Suchitra Sen and many others. “The house I lived in [which she eventually had to let go off], at Park Circus, was palatial. I would come back in the wee hours, exhausted. Then, I would wake up from sleep craving for fish. I would tiptoe into the dining room, sit at the huge table and polish off the katla maachh bhaja that Durga kept for me,” she tells me.

There was a string of relationships, of course. But none that would give her any “guidance or backing”, as she puts it, lamenting her current financial situation. “Perhaps the only man I loved was Robin, an American. He wanted to marry me, take me away…” Arati says, pointing to his photograph on the shelf. The man is tall, attractive and has a kind face. The photo shows him holding hands with Shefali, who looks equally stunning in a black sari and hair tied in a bun. “He loved children,” she adds. Why then did she not marry him? “It would mean leaving my family behind. How would they have survived?”

What does she think of the performances and dancers today? “Every dance form has a character, follows a grammar. But what do these item numbers even mean? It hurts me terribly to see all that goes in the name of dance.” The veteran makes no effort to conceal her disappointment or anger. “Perhaps that’s the reason why I am not invited to dance shows as a panelist,” she says. Not many would know, but the cabaret queen also trained in ballet, Bharatanatyam, Kathak, the folk dances.

In 2012, there was much talk about making a film on her life. Gulbahar Singh, a National Award-winning director, was to helm the work. However, there has been no news of it after that. A biopic based on Arati’s vast and complex experiences may not be more powerful than the woman herself, so just as well.

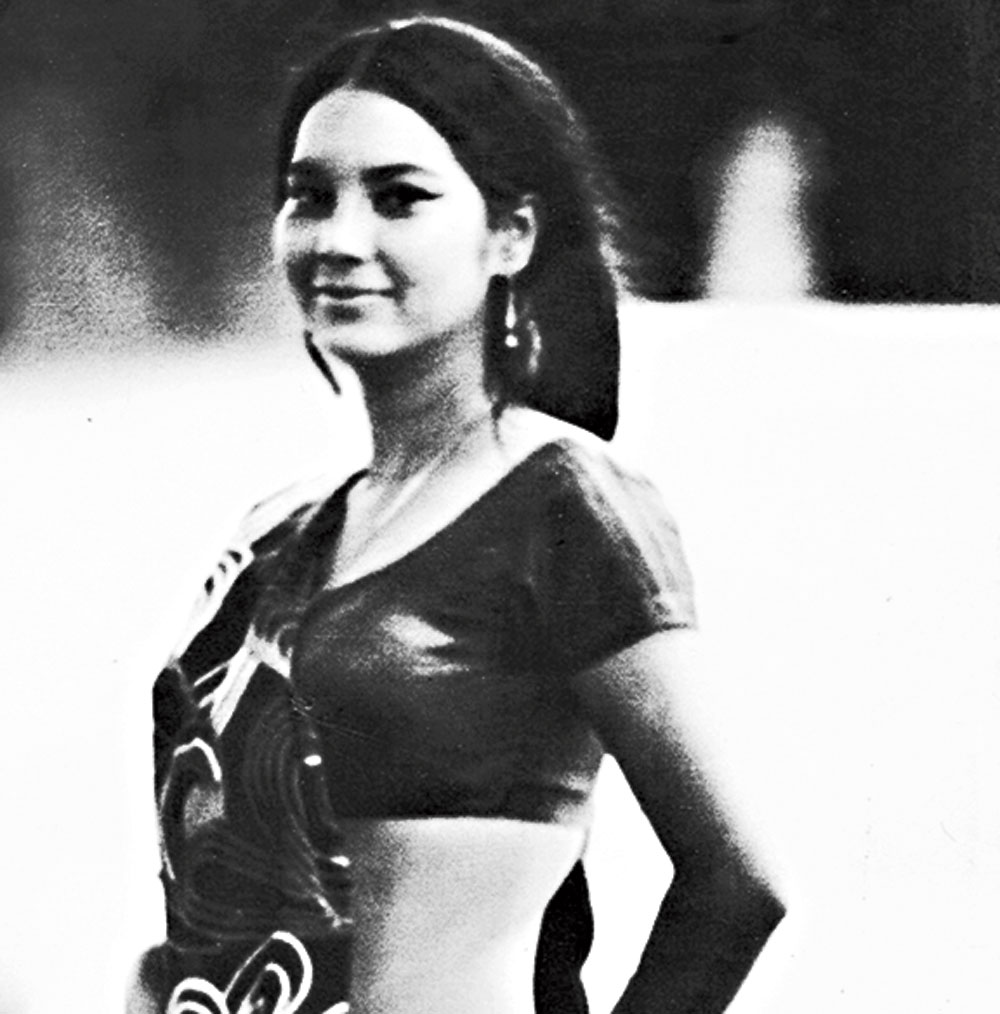

Arati also acted in some films among which were Ray’s Pratidwandi and Seemabaddha Image: Arati Das

Arati’s modest two-room flat is alive with framed photographs of Miss Shefali. She has been living here for 15 years along with her caregiver, Durga, who in turn has been cared for by the dancer since she was five. Durga tells me of all the people her Didi has provided for — and still does — in spite of her difficult circumstances. “Frequent hospitalisation has drained away all her money,” she says.

Arati’s expression betrays nothing. She is excited about the interview, is looking forward to the shoot. “You may ask me anything… mon khuley,” she says. My head is buzzing with curiosity, and I want to hear it all from her, all at once. But I begin at the beginning, which I realise later, is just one of the several. How did she start dancing?

Her story is the stuff of legends, some of which she has penned in a book, Sandhya Raater Shefali (Shefali of the Twilight), published three years ago. “I don’t know how I did it all, but one thing was clear from the start — I feared nothing,” she says, her words measured and tone even. “I was a baby of six months when my parents arrived here from Bangladesh. The poverty I’ve been through in my childhood is unthinkable. Baba was bedridden and Ma worked in other people’s homes. Only after she returned from work did we get to eat, and sometimes not even that,” she continues, despite the tears that have just brimmed over. She reaches for her handbag and pulls out a handkerchief.

“You have such pretty hands,” I hear myself mutter.

She tells her tale and every detail from childhood is vivid, every family member dearer than the other. The lal pulish (red-pagri police personnel), the hajak alo (gas lamps), the sahebs and memsahebs strolling by the river. The “exquisitely beautiful” elder sister who was married off the “arranged” way and who is “khub rasik” or very witty. The beloved younger brother, the proverbial prince, whose untimely death feels like a fresh laceration to her heart, at every mention. “That was five years ago,” Durga chips in. “How could you say that?” Arati almost reprimands her. “It’s not five yet.” And what about her parents? “Amar ma khub shundor chhilo, bojhdar chhilo… My mother was beautiful, and wise.”

Arati was 11 when she started working in an Anglo-Indian household in Chowringhee. “Every evening, they would have parties, with lots of music and dance,” she says. “I used to watch from behind the curtain, these high society people and their swinging and swaying. When I was called in to serve food, I would drag my feet — stretching my time spent there — so that I could closely observe their steps and hand movements. Later, in my free time, I tried to imitate those moves. I could in no way match up to their dancing, but I longed to. It became an addiction…”

Among the regulars who visited the house was a man called Vivien Hansen, who sang at Mocambo restaurant on Park Street. Little Arati often asked him if he could find her a better job. After much pestering, Vivien relented. “Can you dance,” he asked. And she said, yes. “We secretly planned to meet near the tramlines at Dharamtala crossing one afternoon. I stole out of the house, carrying just a couple of skirts and shirts, whatever my employers had given me.”

That day Vivien took Arati to Firpo’s on Park Street, the poshest restaurant of the times. “Their bread was famous,” she tells me. That day she got angry with all those men talking among themselves in English, not asking her to sit even once. “Ultimately they agreed to hire me; my salary would be Rs 700 a month. I was stumped, it was a fortune!”

The evening, however, did not end there. Arati was made to dress in a sari and high heels — which she couldn’t manage; she kept falling — and taken to Lalbazar. Tell the officer your parents are no more, and you need to earn a living, Vivien coached her. Recalls Arati, “The officer treated me very harshly. A Bengali girl wanting to do the cabaret, he scolded. I did not understand what cabaret meant, but shot back at him — Apni amarey khaitey diben, apni amarey portey diben? Ami ki kori na kori oto koiphiyot dimu kyan?… Do you pay for my upkeep? Why then should I be answerable to you?” This time her tone is not even.

The officer issued her a licence for three months. It was a time when most European dancers were leaving India, and this opened up the space for local women. Her very first show was a huge turning point. Of course, before getting in front of all those people she had cried her eyes out on seeing the dress she was to wear — it included a bikini-blouse, her arms and legs were left bare. But eventually she steeled herself to give it her best. She says, “There were so many musicians for me — on the drum, saxophone, guitar, trombone, trumpet. Once on the floor, the famous Lido Room, I danced as if there was no tomorrow. And when it ended — it lasted over half an hour — the applause was unbelievable.”

And thus began her life as Shefali, as “David sir” christened her. There were tutors for almost everything — various dance forms such as the Charleston, Can-Can, Twist, Hawaiian hula and belly dancing; spoken English and Hindi; social etiquette; make-up, exercise and what-not. “The rehearsals would be so demanding that there was no time for food even, although we were allowed to eat very little. Only juice was unlimited,” she says.

If only you had the eye for it; if only a way of seeing. There are those who do. Else, nothing about Arati Das tells you of the trailblazer that she is. If you spotted her taking a rickshaw from her nondescript north Calcutta neighbourhood to the doctor’s chamber a few blocks away, you wouldn’t guess that this 72-year-old woman — with somewhat relaxed reflexes and difficult gait — once danced the night away, her unbridled act pleasing her own self as much as roomfuls of “high society” men.

Yet, if you broke a few walls and gave in to her simple queries, you would still catch glimpses of Miss Shefali, who in the ’60s and ’70s rocked the cabaret space of the city’s nightscape, set the bar-room and much else on fire.

“Are you going to click my pictures with your phone,” she asks, a tad disapprovingly. I assure her that a professional photographer would visit her soon and this perhaps elevates my position slightly.

Arati Das worked in the nattiest restaurants of Calcutta Image: Back cover of Sandhya Raater Shefali