The message on the postcard addressed to one Professor N. Sastri reads thus: “…we have shifted to another camp in the hills… you should not worry at all… this place is quite healthy and the water quite excellent.” The postmark stamped on the bust of King George VI, shows the date and place of despatch (November 8, Johi, Sind) and receipt (November 13, Sylhet). The postscript says: “I shall be back to Calcutta by December 24 (1938).”

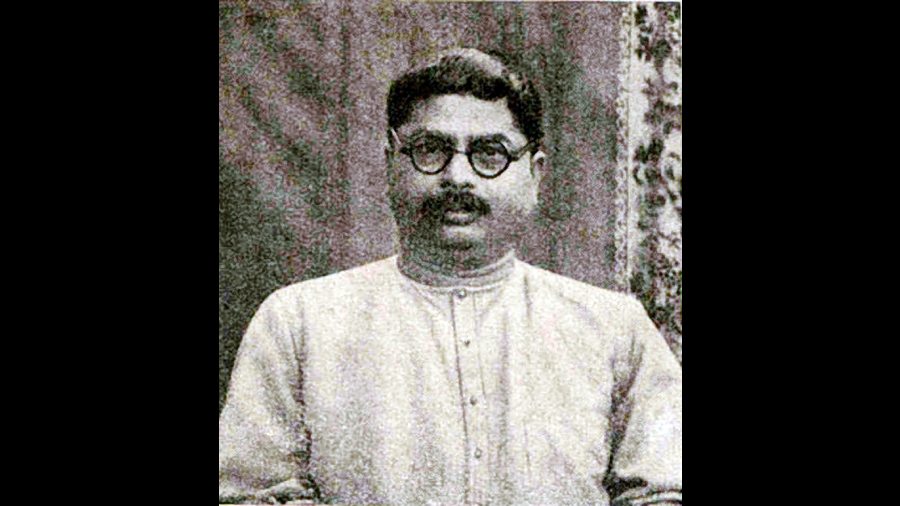

The sender, archaeologist Nani Gopal Majumdar, never arrived home from his workstation at the camp at Rohil Ji Kund near the town of Johi in Dadu district of Sind, now in Pakistan. Instead, his wife Snehalata, three children and father-in-law (Prof. Nalinimohan Sastri) received an urn containing his ashes weeks before his 41st birthday on December 1.

At the crack of dawn on November 11, 1938, Majumdar had been shot dead by a band of robbers who, as the story goes, mistook him and his team for treasure hunters.

Majumdar was in Sind for an archaeological exploration in the Indus Valley that would eventually push back the civilisation’s antiquity beyond 4500 BCE. Before his discovery, it was believed that the period of the Indus Valley Civilisation was 3300-1200 BCE. It was Majumdar who established that there was a pre-Harappan culture. Mind you, all this was happening 15 years after Rakhaldas Banerji had discovered the remains of a Bronze Age (3300 BCE to 1200 BCE) city at Mohenjodaro, 140 kilometres south of Johi.

After the discovery of the Indus Valley Civilisation — exactly a century ago — and the twin cities of Mohenjodaro and Harappa, several exploratory surveys were being pursued zealously at Sind and Baluchistan by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), headed by Sir John Marshall. Marshall, impressed by Majumdar’s erudition — he was an epigrapher, a museologist and Sanskrit scholar — had chosen him as the leader of the expedition in the hill tracts of Johi.

Ravindra Singh Bisht, a former joint director of ASI who specialises in the study of the Indus Valley, says, “NGM — that’s how Majumdar is known in the archaeological circle — discovered around 62 sites, most of which were from the pre-Harappan or early Harappan period (4500 BCE or before).” He also pointed out that Majumdar’s memoirs titled Explorations in Sind is considered a masterpiece of archaeological report.

Majumdar’s two outstanding discoveries were the sites at Amri and Chanhudaro in Sind. “Marshall liked him so much that he personally trained the 24-year-old museologist during the excavation of Mohenjodaro and then straightaway appointed him assistant superintendent,” says Bisht. Within four years, he was promoted and became a superintendent. A remarkable achievement considering he was a “native” in an organisation dominated by British bosses.

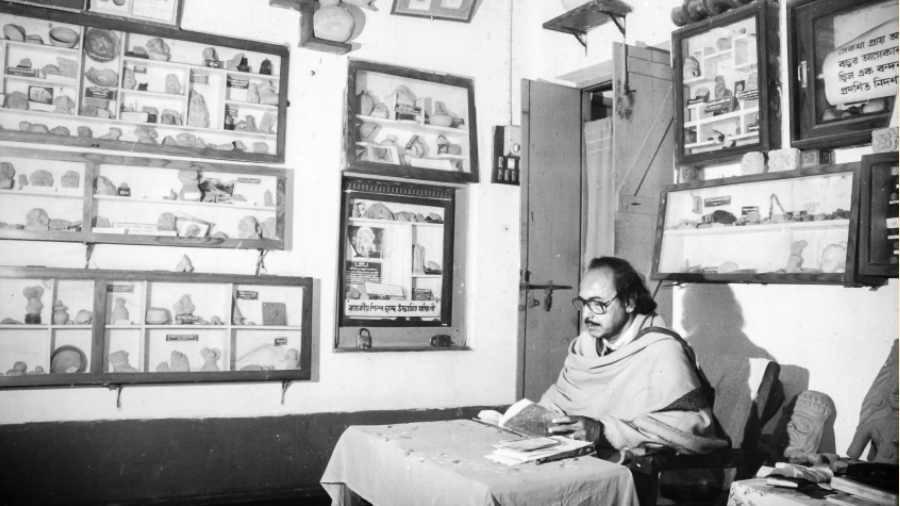

Before he joined the job, Majumdar was a curator at the museum of Varendra Research Society in Rajshahi (now in Bangladesh) and had mastered the art of deciphering ancient inscriptions. He was inducted as a fellow — the youngest then — of the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal for his “erudition in Oriental learning” and “contribution to Indian archaeology”, well within two decades of his career.

His death, quick post-mortem and hasty cremation at Dadu, all in the span of 24 hours, still remains shrouded in mystery.

Prof. Aziz Kingrani of Dadu in Sind, Pakistan; signboard near the Kirthar mountains where Majumdar was killed Courtesy, Wikipedia and Aziz Kingrani

Aziz Kingrani, a college professor at Dadu, is an admirer of Majumdar. He says, “The robbers were arrested at Kalat (Balochistan) and sentenced to life soon after Majumdar’s death. But their identity remains a mystery. When I tried to trace the records of his post-mortem and murder trial, I didn’t find anything.”

Kingrani has visited more than once the site near the foothills of the Kirthar mountains where Majumdar was killed. “With the help of friends, I erected a memorial signboard in 2011,” he says. Kingrani shared photographs of the board with The Telegraph.

Although Sind remembers Majumdar’s contribution, in India he’s largely forgotten. His grandson Anjan Mukherji, who is a professor emeritus of economics at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University, says, “There is an overwhelming sense of regret (in the family) that the government didn’t do anything to recognise my grandfather’s contribution.”

In fact, the family received no official intimation from the government when Majumdar died. Snehalata came to know about it, by chance, as she was listening to a radio bulletin. The news, however, was covered in Calcutta newspapers including Anandabazar Patrika and The Hindustan Standard.

Mukherji recalls, “My mother (Dipti) was 15 and was about to appear for the Class X board exams. She was in Sylhet at her grandfather’s house at that time.” Since Majumdar moved about on excavations across India, the family stayed either in Calcutta or in Sylhet. All members congregated in Calcutta whenever he returned from expeditions.

His father’s death had deeply affected Majumdar’s 10-year-old son Tapas, who later became a professor of economics at what was then Presidency College. Economist Dipankar Dasgupta, who is also a columnist with The Telegraph, recalls the highly revered professor who was always reticent to talk about his father. He says, “Despite having to bear with the tragedy at a very tender age, his performance in school and college was exemplary. He joined Presidency College as an assistant professor of economics at 21 and none other than Amartya Sen and Sukhamoy Chakrabarti were his students. Following in his illustrious father’s footsteps, he encouraged students to do research.”

Mukherji remembers Tapas as his dear “mamu”. Every once in a while he still gingerly turns the crumbling pages of his uncle’s scrapbook in which he had pasted cuttings of newspaper reports of Majumdar’s death along with some of the letters, including the last postcard. The family also has a field diary of Majumdar, which is full of copious personal notes about his expeditions.

Amateur archaeologist Sandipani Bhattacharya has taken up the task of bringing out a commemorative volume on Majumdar on his 125th birth anniversary this December. “I am also digging out all the research papers, articles and field notes of this archaeologist who was much way ahead of his time. I wish to bring out a five-volume complete works of Nani Gopal Majumdar,” he says. Bhattacharya notes that Majumdar — a “native” — was so confident and passionate about his research that he didn’t hesitate to argue with Marshall, his British boss.

Says Bhattacharya, “Since this year is the centenary of the discovery of Indus Valley Civilisation, it’s the opportune moment to revive his contribution that has largely sunk into oblivion.”