In 2021, the US returned 248 stolen antiques to India in the “largest restitution” of recent times. Among these were terracotta fragments, shards of pottery and stone beads from Bengal — remains of Chandraketugarh, a much-vandalised 2,500-year-old archaeological site, 40 kilometres northeast of Calcutta.

According to experts, while the majority of such items has been smuggled out of the country, a fraction continues to remain in the safekeeping of some amateur archaeologists and private collectors.

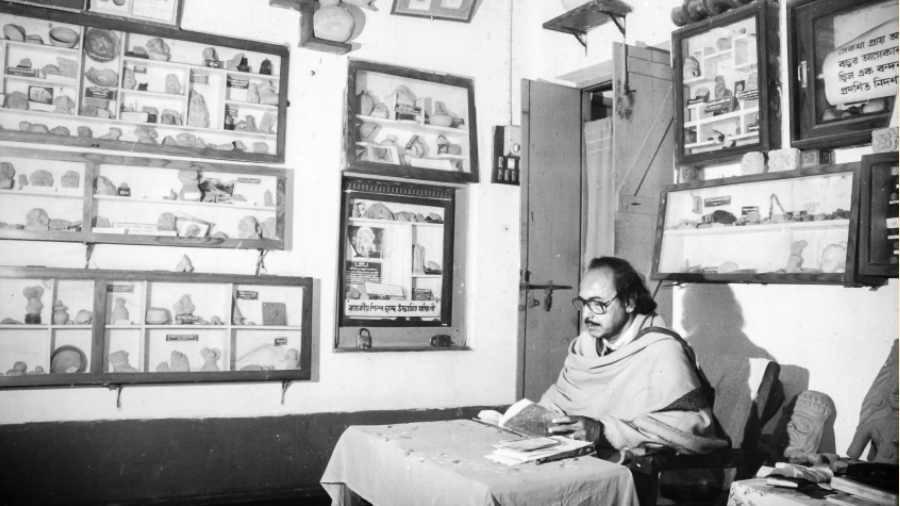

Dilip Kumar Maite, a retired schoolteacher, was one such person. The amateur archaeologist died three years ago and thereafter his collection — 524 pieces — was donated to a museum run by the state government in Berachampa village. Maite’s son Dipan says, “The valuation of my father’s collection is over Rs 100 crore. But he resisted countless offers from collectors and smugglers.” According to Dipan, his father donated his collection to the state government on the condition that the museum housing it would have to be built close to where he lived. He did not want it to languish in some corner of a faraway museum.

Among Maite’s huge collection were terracotta fragments, coins, beads, items made of ivory and bone dating back to the 3rd century BC, basically the pre-Mauryan period.

Goutam Dey, a photographer who has been documenting artefacts from Chandraketugarh, says collectors like the late Maite have worked selflessly for years to protect the precious remains from smugglers and their middlemen. He talks about two other amateur archaeologists — the late Abdul Jabbar and Asad-uz Zaman — also living near the Chandraketugarh ruins, who have made private museums of their assiduous collections. Dey says, “These people are very open to queries from researchers and enthusiasts. They readily show their collection to whomever is interested and the artefacts are registered with the state archaeological department.”

Gautam Sengupta, former director-general of the Archaeological Survey of India, says, “These ‘amateur archaeologists’, despite their lack of training, are passionate about understanding local archaeology.” Their personal initiatives also help build awareness among locals. This way they create a mass movement stemming from a mass awareness and protect the antiquities.

Sengupta speaks of Jogesh Chandra Purakriti Bhavan, a state museum in Bishnupur, 140 kilometres northwest of Calcutta. The museum was started in 1955 by several amateur archaeologists. Three years ago, The Telegraph had spoken to Chittaranjan Dasgupta, one of the co-founders. Dasgupta, who was in his nineties, died last year. Back then he had narrated how he, along with 52 others, took up the task of setting up a museum for manuscripts, coins, pot shards, jewellery scoured from Bankura, Purulia and Midnapore. The retired schoolteacher had said, “None of us was a qualified archaeologist, but we hunted for relics and rare artefacts across southern Bengal to save this wealth of history from curio sharks.”

Shortly before his death, Dasgupta finished writing about his experiences in a colossal book titled Dakshin Paschimbanger Murtishilpo O Sanskriti. Debishankar Middya built the Sunderban Pratna Gabeshana Kendra, a private museum at his residence in Kashinagar near Raidighi, 80 kilometres south of Calcutta. He travelled across vanishing islands and receding coastlines of the Sunderbans to piece together a pre-history he claims is nearly 4,500 years old. “Every cyclone throws up a cache of ancient relics,” says Middya, who runs a wholesale business of medicines for a living.

Among his varied collection there are objects ranging from neolithic tools to ancient potsherds, prehistoric bone weapons and even seals. He has donated many objects to state museums. His work and articles have inspired many young people to rescue antiquities and organise relic hunts in various islands of the Sunderbans.

Middya’s early inspiration was another amateur archaeologist, Kalidas Datta from Joynagar-Majilpur, a town in South 24-Parganas. Datta, who died in 1968, had been a prosperous landowner. His formidable collection is proof that the coastal region of Bengal was part of a major maritime trade route between northwest India and countries beyond the subcontinent, between 1st century BCE and 3rd century AD. The collection eventually came to be housed in Kalidas Datta Smriti Sangrahasala in Joynagar.

Sheikh Ashraf Ali of Burdwan’s Mangalkote got interested in archaeology while he was in high school. “A team of archaeologists and research scholars from Calcutta University came for an excavation in 1986. They allowed me to work at the site,” he reminisces. He learnt that Mangalkote holds archaeological remains of four ancient cultural periods from around 1000 BC.

By the time Ali completed his master’s in history, his interest in excavation had only grown. His day job though is running a private primary school in Mangalkote. Items from his collection have sparked many research projects. He, however, expressed some discontent over the fact that many scholars often consult him and even borrow relics, but never credit or return them. “Many of them even claim my findings as their own,” he says.

Dey, who documents archaeological ruins and relics, agrees. He says, “You’ll find my photographs of Chandraketugarh in many books and websites with no credit line or acknowledgement.”

Gautam Sengupta says, “It is true, these people often don’t get the respect and credit that is their due.”

For most, their work and passion remain its own reward.