Alladi Krishnaswami Ayyar, a member of the drafting committee of the Constituent Assembly, “firmly believed that the real test of any Constitution was how it would play out in the hands of ordinary Indians”. Conceding the ambiguity of ‘ordinary’, streets in India’s cities and towns in the last few months have become spaces where the ordinary people debated the constitutional propriety of certain decisions of the current regime. This is the turmoil of the moment, when deliberations over constitutional principles and procedures reverberate in street level politics, much of which is party-led, but a conspicuous part is non-partisan — led both by revered political values codified in the Preamble and by the raw emotion of fear of individual and collective loss of entitlements both as citizen and as human being. Curiously, trust and cynicism in their various shades dispose the contenders in their respective readings politics of coercive branding of domicile Indians and its larger context of neoliberalism twining with soft authoritarianism. Popular discontent with regimes has been significant, particularly since the neoliberal turn. But this time expressions of sectional restlessness have touched a new high and also coalesced into a social alliance. Apparently, the Constitution has become the only authentic political text to restrain rapacious regimes. That the people celebrated the Constitution as a powerful inspiration for their legitimate claims-making against the policies and practices of the regime and the State, suggests a grasp of the spirit of the Constitution and the laws.

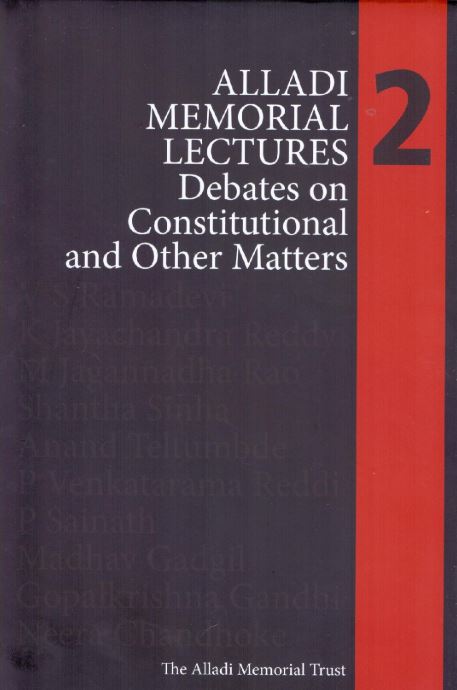

This is where the significance of Alladi Krishnaswami Ayyar and the commemorating volume, the Alladi Memorial Lectures 2: Debates on Constitutional and Other Matters lies. Like the earlier volume (2009), it intends to apprise the general public of the various debates in constitutional law, to affirm political and constitutional morality, to lament institutional corruption which undermines the guarantee of freedom and equality, and to critique the political infringement of the Constitution.

Ten articles, based on lectures delivered between 2005 and 2018, engage with the issues that frame the present agitation by the Indian people except those who make a feast from “the corporate predators’ unhindered drive for accumulation by dispossession of poor people, without making an iota of change in the Constitution”, and the birdbrains. This is the political economy context of the current popular outburst over a State-mediated threat to a vital sense of belonging to the national community, which subsumes but surpasses the statist notion of citizenship. The papers are well-argued and draw their strength from the historical analysis of social time and of the evolution of laws.

Alladi Memorial Lectures 2: Debates on Constitutional and Other Matters, Tulika, Rs 695 Amazon

Readily compliant governors dissolving the assembly, the commercialized media deviating from professional ethics, an infrastructurally inadequate judiciary denying the poor access to justice, and the State abdicating its obligation towards children’s education — all such developments inhibit the process of the deepening of democracy and the firming up of the Constitution. The continuing predicament of the rural poor and the tribal people’s loss of access to the natural commons add to the narrative of regime failure. All these can be traced to the “continuum from liberalism to neo-liberalism”, marked by ‘Social Darwinism’: “the strongest or fittest should survive and flourish in society while the weak and unfit should be allowed to die”. The “deplorable demolition of the proactive welfare state” points towards that. Equally grave is the rise of the police State in which “a petty policeman” “can snatch [common man’s] all [...] rights with impunity”. This is despite the constitutional provision for judicial review to ensure the rule of law: “non-arbitrariness in state action”. The arbitrary State refuses to comply with the principle that majoritarian power should abide by judicial directives. While much of these is audio-visually circulated through the media, what remains largely unnoticed are regime violations of the Directive Principles of State Policy, “the soul of the Constitution”, in the last 20 years. These Principles “are about what should be, what ought to be; and, they offer us a vision of [a just] society”. In fact, these define State duties. The most critical among these is that the State must “strive to minimize inequality, inequalities in status, facilities and opportunities not only amongst individuals but also among groups of individuals residing in different areas and engaged in different vocation”. The precarious state of secularism and of free thought is distressing. There is no guarantee that “people can pursue their faith or any other substantive conception of the good unburdened by discrimination”. Much more dreadful are the leaders’ infectious indulgences in incivility. “In our times, abusive speech has displaced plain old-style honesty, obfuscation has put frank directedness out of work, and verbal abuse of a hundred vulgarities has thrown the traditional martial art of stately vehemence out of office. Ambedkar alerted us long time back: ‘If things go wrong under the new Constitution, the reason will not be that we had a bad Constitution. What we will have to say is that Man was vile.’”