Book name: Qabar

Author name: By K.R. Meera

Publisher: Eka

Price: Rs 399

K.R. Meera has persistently written about love that inflicts grievous wounds — the love may be for the country, for a cause, or for a man, but its victim is mostly a woman. She shows that political, religious and domestic violence leave equally deep scars on the body and the soul of the woman, some of them self-inflicted. Qabar — translated from Malayalam by Nisha Susan — is no different in that women are at the centre of it. But it goes beyond the wounds of love. Meera uses magic realism to ponder disquieting truths that plague the world at present.

Qabar is the first-person narrative of Bhavana Sachidanandan, an additional district judge and single mother to a boy with ADHD. The plot oscillates between the staid reality of Bhavana’s existence and the realm of the supernatural conjured up by her mind every time she catches a whiff of the Edward rose perfume worn by Kaakkasseri Khayaluddin Thangal, one of her plaintiffs. Thangal petitions the court to prevent the destruction of an ancestor’s qabar located on a piece of land that has been sold off without his knowledge to a charitable trust.

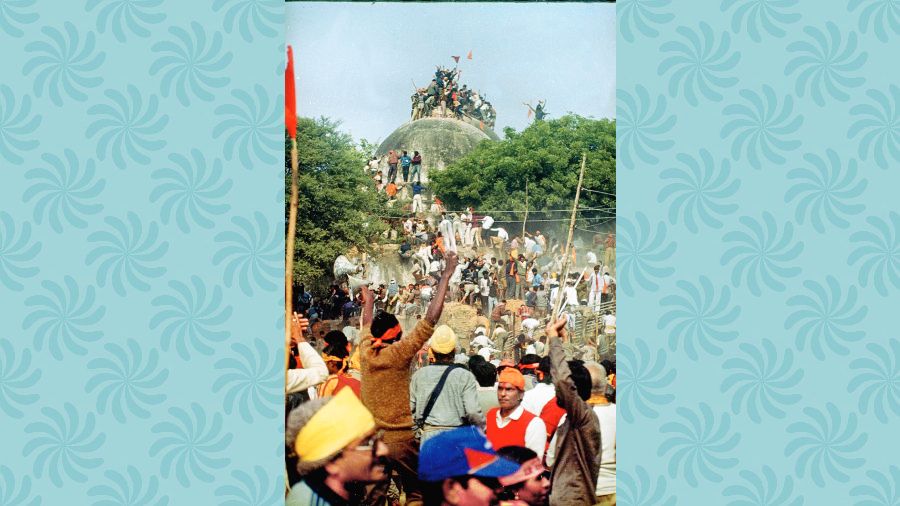

Meera fuses fiction and fact dexterously. In 2019, when Bhavana is hearing this fictional case, the Supreme Court was delivering its verdict on the demolition of the Babri Masjid, another historical structure that was razed to the ground. Meera questions the way the law functions in India. The legal system favours the privileged, we are reminded time and again. Bhavana, fuelled by her resolute faith in the rightness of the law, sees herself as an upholder of justice. The law demands evidence, she states. In a conversation that reads like a commentary on recent verdicts on land disputes, she asks Thangal: “[d]oesn’t your objection stand in the way of public interest? And even if you argued that the qabar has historical importance, you don’t have any documents to prove it do you?” Bhavana’s courtroom has no space for sentiment or faith. And yet, as she discovers, the qabar exists, both as the ruins of a structure with minarets as well as in people’s imagination. History, Meera forces us to see, is made up not just of facts and transactions documented on paper but also of lived experiences, of socio-cultural practices, and of collective memory.

The book is also suffused with Meera’s strong feminist ideals. Her women protagonists — Bhavana and her mother — defy and question patriarchy at every turn. Both women walk out of toxic marriages and make informed choices to cast off the burden of societal expectations. Echoes of Mary Wollstonecraft’s idea of equality in marriage and Virginia Woolf’s insistence on women needing a room of their own abound. But the most interesting aspect of Meera’s feminist vision is her exploration of family history and how it changes when it is retold by women.

Gabriel García Márquez had said that “[w]hat matters in life is not what happens to you but what you remember and how you remember it.” It is this fluidity of memory that becomes the basis for Meera’s critique of the inadequacies of the legal system, communalism and patriarchy. She does not try to provide easy answers. But there is a discernible quest for greater understanding and for accepting historical wrongs as the first step towards righting them.