Book: Unmasking Indian Secularism: Why We Need A New Hindu-Muslim Deal

Author: Hasan Suroor

Publisher: Rupa

Price: Rs.295

Both the idea of Indian secularism and its practice are buffeted today by the harshest winds since the Partition and the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi. The popular majoritarian hate that has engulfed most kinship, friendship, workplace and media spaces has spurred immense anguish, introspection and despair among all Indians, but most of all among Indian Muslims. One meditation on ways out of this crisis is a slim, but provocative, volume by the London-based journalist, Hasan Suroor. His central thrust is to urge Muslims to accept India’s transformation into a Hindu nation in a new ‘Hindu-Muslim deal’.

Muslims, he believes, need to make hard choices given the widespread Hindu sense of both entitlement (of having the first right to India) and grievance (real or imaginary). They must accept Hinduism as the official religion of the Indian nation, and demand in return that their civil and religious rights are protected by law. It is only by abandoning the idealism of secularism, Suroor is convinced, that Muslims can find a way out of their current misery, and the country can be united.

He makes many questionable assumptions. One of these is that Hindus as a whole today reject both secularism and Muslim rights. But in reality, Hindus are extremely diverse in caste, sect, gender, beliefs and practices. It is unscientific to make generalisations that homogenise all Hindus as following a common set of religious, cultural or political beliefs. Empirically, Hindutva hatred and violence are countered and fought significantly by other Hindus. Equally, Suroor generalises problematically about Muslims, such as his claim that Muslims never had a stake in secularism, and would have been content with a Hindu nation as long as it guaranteed their citizenship rights.

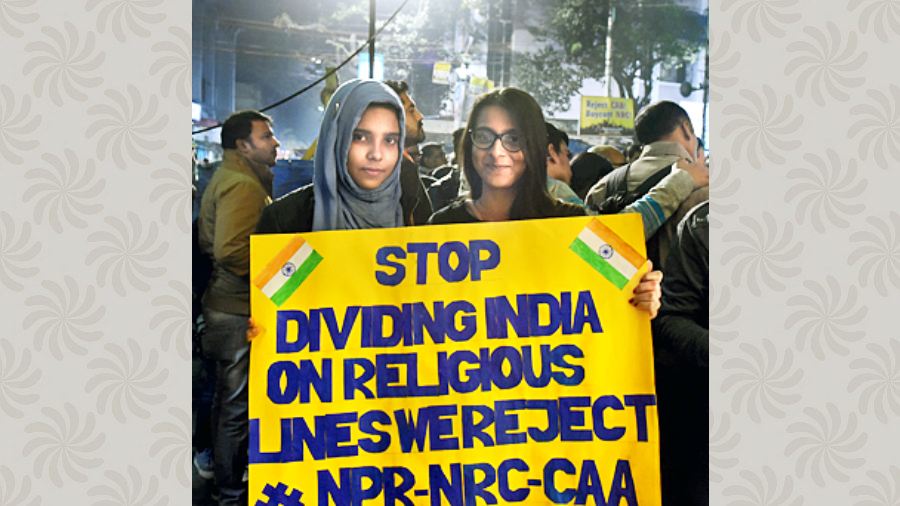

His account of the protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, I think, also falters on two grounds. One, he describes it as a movement of Muslims against the pointed discrimination against them in the new law. On the contrary, I testify to a large participation of people of other faiths in solidarity with India’s Muslims, especially in campuses. This was not just the largest non-violent protest that the country has seen since the freedom struggle but also the most emphatic demonstration of HinduMuslim unity since the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi. Suroor is also wrong to describe the protest as a failure. It might have been crushed by State action, but the collective resistance of Indians of all identities standing together in defence of the Constitution marked an emphatic assertion by the people of their collective faith in the values of the Constitution, specifically in the idea of secularism. The movement may have been throttled, but that it happened at all is its abiding success.

Suroor’s counsel, as stated, is that Indian Muslims must accept the reality of a Hindu rashtra and seek citizenship rights in return. Secularism, according to him, is unravelling because the idea of religious neutrality was a Western implant in a society that historically was deeply religious and, thus, destined to fail. He admits that adopting a secular Constitution played a laudatory role in extending a sense of security to a traumatised minority, unsure of its place in a Hindu-majority country. But he argues that today, instead of fostering communal harmony, it has bred resentment within the majority community, which believes that secularism unfairly benefits India’s Muslims; that such “pseudo-secularism” masks a cynical policy of “appeasement” of Muslims as a captive votebank. Muslims, too, have not gained from policies of “secular parties” like the Congress that have kept them poor, dependent and fearful.

Suroor argues that his advocacy of Muslims embracing the abandonment of the Constitution is not as an act of surrender but of realism. Secularism for him was an idea nurtured by the left-liberal elite but not embraced at its core by the mass of people.

I understand Suroor’s anguish, but passionately oppose his suggested remedy. India’s secularism was never intended to mandate the denial of faith in public life; it was the pledge of equal respect for every faith, including the absence of faith. This is an idea with ancient civilisational roots in India, from Ashoka to Akbar to Gandhi. The practice of this idea may have often faltered, but not the idea itself. Therefore, the Hindu-Muslim deal for a peaceful and just future does not lie in abandoning the idea of secularism, but instead in renewing collectively a commitment to its robust defence against all storms that are released against it.