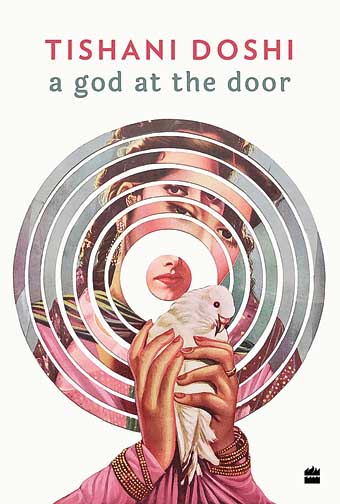

Tishani Doshi, author, poet and dancer, found herself responding to news articles in the pandemic with poems that have now been collated into a stunning book called A God At The Door (HarperCollins India; Rs 499). Over 50 poems come together to create a narrative that is filled with empathy, fury and social consciousness. The list of poems include In a Dream I Give Birth to a Sumo Wrestler, Tree of Life, I Don’t Want to be Remembered for My Last Instagram Post, Instructions on Surviving Genocide and After a Shooting in a Maternity Clinic in Kabul. Doshi, who teaches at New York University in Abu Dhabi, spoke to us on Zoom, about her poems and experimenting with the landscape of poetry on the pages of her book. Excerpts.

How and when do you understand that you have a robust collection of poems with a central theme that can be made into a book?

It changes from book to book. With every book that you write, you find a new way of figuring it out, particularly with poetry. I always think that I will start out with a concept and that the poems will work towards a large idea of the book but it never turns out like that. I usually just write individual poems. And then I arrive at a point where I think I finally have a critical mass. This book was slightly different in that I had been writing poems in response to a lot of news articles. Prior to that, I think poems were travelling inward out so I would feel something. But here it was the outside that was triggering something that would then make me connect to it.

The whole pandemic last year made the themes appear very clearly to me and the poems had a certain urgency. With all of us stuck to our screens, I started thinking about how much the news was shaping us. So a lot of the poems are trying to interject and say something about our relationship to the news and how the news cycle can desensitise us. Poems require you to shift as a reader, even though it’s using the same language. The language is English in my case, but what a poem is doing is to transform that language. And rather than desensitising us by hammering us with news, it is sensitising us and trying to make us think about what it means to be human and alive.

The Telegraph

And why is God at the door?

In the second last poem Hope is The Thing, which is kind of a riff of Emily Dickinson, I try to look for what we can still think of as sacred or holy. How do we make connections with things that are outside us? In the poem, a line comes ‘guard at the door’ and the guard is sitting on a black buffalo and I am referencing Yama, the god of death. But there are lots of gods and spirits and goddesses and all kinds of magical figures in the book and the doorway has always been important to me –– the threshold, the point of entrance.

In a dance theatre, you cross the threshold, and you’re immediately into the space which is different from your outside space. It’s the space where things happen, where things are created. So the idea of the God at the Door is the possibility of a spiritual sacred being that is just within reach. It’s at the threshold which doesn’t mean we are always able to reach and connect with. It is largely because I have been trying to think about where we can find hope. It is very easy to get pessimistic.

Lot of my poems are trying to grapple with very big issues. So I don’t want to lose sight of the fact that hope is also an essential human response and that we have had it even in the bleakest of times. I want my poems to have a little bit of hope, joy and laughter as well.

What is your writing process like when you’re writing prose, as opposed to writing poetry?

I’ve been writing a lot of essays and I think that’s a wonderful form for me because it is contained in some way. Writing a novel takes you out of reality in a very strange way because it requires you to create another universe in your book. Whereas while you’re writing poetry, you are, of course, always in the state of creation somewhere else. And poems are also more self-contained I feel. There is a great sense of accomplishment when you finish one. It’s harder to get that feeling in a novel.

However, I think it mostly has to do with time. When you’re dealing with time in a novel, it’s really this huge, capacious thing that you have to hold inside your body and your head. Whereas a poem, though small, can be huge in that it’s saying a lot in so few words, but it doesn’t bog you down by time –– you don’t feel oppressed in that sense.

There is a lot of anger in this book of poems since they are in response to news articles. Would this anger find space in your prose?

I think the work is always in dialogue with each other. For instance, when I wrote my previous book Girls are Coming Out of the Woods, I was also writing Small Days and Night, so a lot of the themes spill over into both books. Whether it’s a question of gender violence, or whether it’s a question of dogs, or whether it’s a question of belonging, or home, or identity, or any of those things, I think you find them in both forms. And in prose, it’s not like it’s a different subject matter, it’s just dealt with differently.

Is it possible for art to exist without social consciousness?

The idea of art for art’s sake, right? Of course, it can. But I think even that comes out of the particular time that you’re living through. I’m always interested in how poetry particularly can be very tied to a historical moment and a particular time. But because of the lyrical element of poetry, it also has something very universal. There are poets like Neruda who wrote during the Spanish war. His political poems are so different from his love poems in a way that the latter has another life from not being tied down by history. And I think there are other poets who combine them both in one poem that are political and personal at the same time. I really think that this ability of poetry to straddle many time zones to be absolutely contemporary. Transcending the contemporary is what I aspire to.

Could you share your thoughts on the landscaping of poetry on the page in this book?

I really wanted to play with shape a lot in this collection. The poem I Carry My Uterus in a Suitcase came out like a Yoni, a triangle and I was so pleased with that because I felt that form. And I use form a lot. Within Indian traditions, there has been a combination of visual and sonic. If you think of like yantras and mantras for instance, there is that sense. I think for me, poetry is really as much about the words as it is about the sound as it is about how it is seen. So it’s more to do with the sense of play. I hope that some sense of irreverence has come through.

What are you reading right now?

I am teaching Jericho Brown’s The Tradition in class, which won the Pulitzer Prize. It is a wonderful book that also deals with masculinity, with queerness, with black bodies, with police brutality, but it’s also about claiming ancestry and finding beauty.