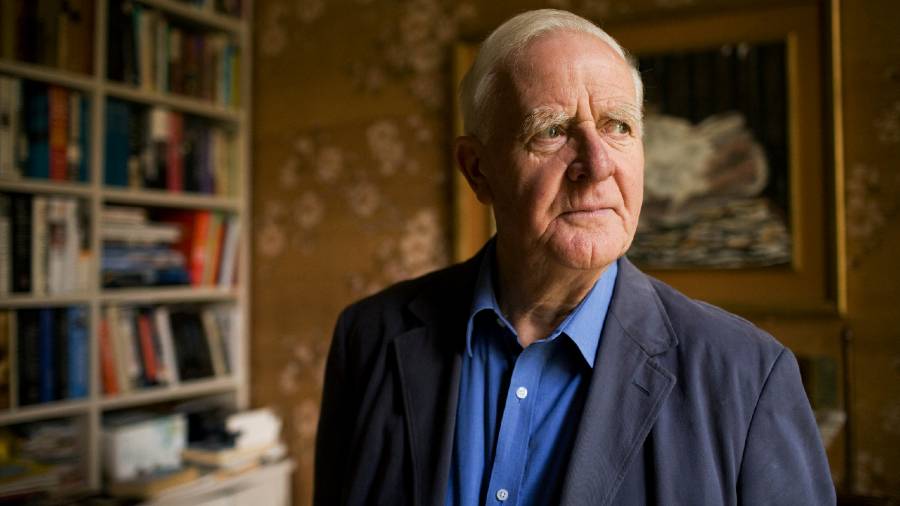

My grandfather, who was born in the 1920s and lived until 2001, was a moody and irreverent man with many one-liners to his credit, which continue to be quite popular in our family. He enjoyed watching cricket on television, only watched American Westerns when it came to films, and read all the time but rarely was interested in reading novels, except espionage thrillers. He was a great admirer of the English right-arm off-break bowler, Jim Laker, and one thing he sometimes said is stuck in my mind even to this day: “Only Laker ar le Carré, baki shob bekar (loosely translates to “Only Laker and le Carré make sense, rest are all useless.”) That was my introduction to the spy-turned-bestselling-writer David John Moore Cornwell, known popularly around the world for his classic Cold War spy novels by the pen name John le Carré.

At the age of sixteen, le Carré had left the English public school he went to in England and fled to Bern, the Swiss capital that later served as a setting for several noteworthy scenes in his books – not only to study German but as he later wrote: “to get out from under my father at all costs”. It was also in Bern where he took his first step towards British Intelligence when he was recruited as a teenage errand boy; “delivering I knew not what to I knew not whom,” he wrote. Every consequential thing that happened later in his life was a result of that one impulsive decision of leaving England and embracing Germany as his new home.

A particular passage from his memoir – The Pigeon Tunnel: Stories from My Life – outlines the expanse of his life’s experiences, which eventually became the central force behind most of his best works: “Without it [flight to Bern], I would never have visited Germany in 1949 on the insistence of my Jewish refugee German teacher, never seen the flattened cities of the Ruhr, or lain sick as a dog on an old Wehrmacht mattress in a makeshift German field hospital in the Berlin Underground; or visited the concentration camps of Dachau and Bergen-Belsen while the stench still lingered in the huts, thence to return to the unruffled tranquility of Bern, to my Thomas Mann and Herman Hesse. I would certainly never have been assigned to intelligence duties in occupied Austria for my National Service, or studied German literature and language at Oxford, or gone on to teach them at Eton, or been posted to the British Embassy in Bonn with the cover of junior diplomat, or written novels with German themes.”

His complex body of work, involving 25 novels, and several film and TV adaptations, warrants critical examination and inquiry, especially today when we are all living in a world fraught with division and despair in the name of nationalistic fervour. A forthright critic of Brexit, in an interview to CBS in 2019, le Carré tersely summarised the difference between patriotism and nationalism, saying, “A patriot can criticise his country, stay with it, and go through the democratic process. A nationalist needs enemies.” The literature le Carré produced during his life is imbued with this unobsessed patriotism and serves as a masterclass when it comes to writing about one’s nation and its workings.

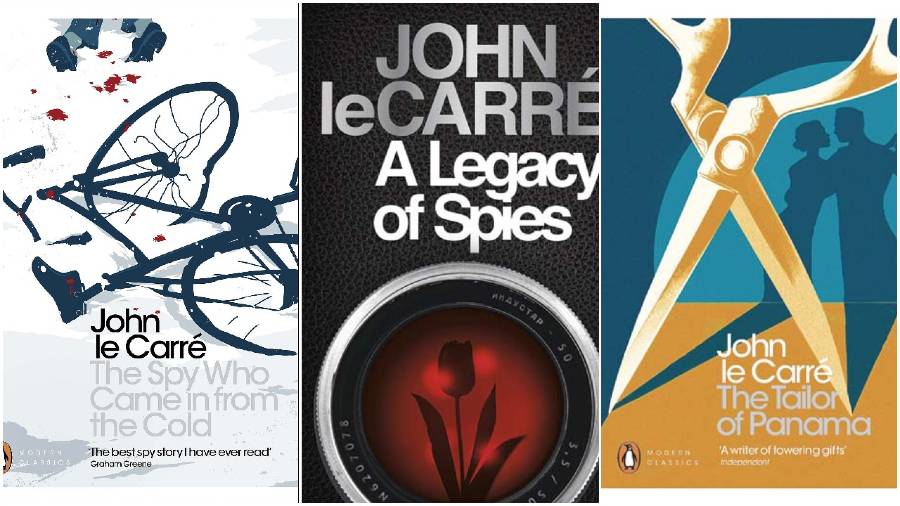

It was his third novel about a British Agent who refuses to come in from the Cold War during the 1960s, and is sent to plant misinformation about a powerful East German intelligence officer, The Spy Who Came In from the Cold, published in 1963, that gained him international acclaim. Throughout his career, le Carré used British Intelligence as an allegory for human civilisation, which has become immoral and conspiratorial, suffering from corporate and political rot. In George Smiley, he intentionally created the very antithesis of James Bond – deglamourising the image of a spy by presenting a short, bespectacled and middle-aged intelligence officer who is cuckolded serially by his unfaithful wife – the protagonist of many of his novels including Call for the Dead, A Murder of Quality, and the very popular Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the most radical and fierce work he published was A Constant Gardener (2001), in which he audaciously attacked the pharmaceutical industry for its exploitation of African nations in the face of the AIDS epidemic.

Throughout his career, le Carré used British Intelligence as an allegory for human civilisation The Telegraph Picture

John le Carré said he chose this name – which simply means ‘the square’ in French – only because he liked the vaguely mysterious, European sound of it. The mystery also lies in how despite having written countless spy novels, his books often were not about espionage at all and rather more interested in examining human fallacies, aspirations, and betrayals. He breathed his last on December 12 of this wretched year, leaving behind him a life that was the coalescence of numerous imperceptible miracles, starting right with his birth. His mother left their home, and in turn him, when he was just five; and there haven’t been many writers who were also born to a conman father, irresistibly charming and deceitful at once, who could convince anyone into believing anything, and ended up serving term in prison presumably for insurance fraud.

The 2013 New York Times profile of John le Carré talks about a framed poster that used to be up on his office wall, given to him by his children that read: “Keep Calm and le Carré On.” And carry on he must even though he’s gone because his stories shall be read, discussed, debated and celebrated for as long as human beings read and write in this world. Admirers and fans of spy fiction will continue to turn to him for inspiration, much like how off-break bowling enthusiasts around the world shall keep revisiting Jim Laker’s old videos on the web. Because those who can spin a yarn as mesmeric as these gentlemen shall be few and far between. His greatest writing tip for aspiring authors perhaps will remain how he began his novels with a character facing a predicament. ‘“The cat sat on the mat” is not the beginning of a story,’ he'd say, ‘but “the cat sat on the dog’s mat” is.’ For millions of readers before and after me, he’ll always be the “disenchanted romantic” as he called himself, the tinkerer who managed to bell the perpetually curious cat inside our ever-surveilling double agent hearts.

The author is a senior commissioning editor at Simon and Schuster India.