Book: Prophet Song

Author: Paul Lynch

Published by: Oneworld

Price: Rs 599

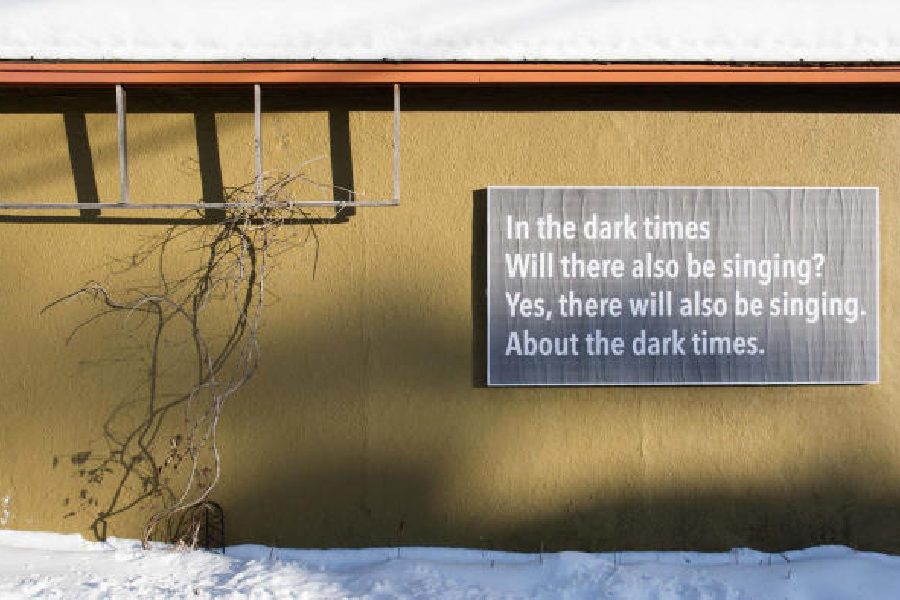

The mood of Paul Lynch’s Prophet Song — the winner of this year’s Booker Prize — is a crepuscular present continuous. The novel is keenly aware of the pronouncement of its epigraph, Ecclesiastes 1.9, that “that which is done is that which shall be done; and there is no new thing under the sun.” But should there be no record, then, of the horror of things that are done in dark times? The book answers with its second epigraph, Bertolt Brecht’s “Motto”, as translated by John Willett: “Yes, there will also be singing./ About the dark times.” The darkest of times that Lynch’s dystopia sings of mirrors our current reality and, as in the simmering rage at the banalisation of evil in Daniel Borzutzky’s poetry, could have wrought emotional devastation. As it is, the book seems unable to transcend its own Ecclesiastes-derived ennui wrapped in present-continuous haze and simply fetches up as mildly distressing.

The story, as the title suggests, is parabolic. Eilish Stack, a microbiologist with a corporate job, a happy marriage, and no less than four children, opens the door one evening to two detectives of the Garda National Services Bureau, which is the secret police that the National Alliance Party has formed to administer the state of emergency that has been declared in Ireland. She is informed that her husband, Larry, who is deputy general secretary of the national Teachers’ Union, has been summoned for an interview. Very soon Larry is “taken”, along with many others, never to be seen again. A passport is denied to her infant son, her eldest son joins the rebels, and a slow crumbling of the fabric of civil society under tyrannical government and civil strife, as experienced by an affluent, well-educated, middle-class family unfolds with tragic inevitability. Eilish’s stubborn will to hold her family together upon her native soil is inexorably ground down by senseless violence, blind cruelty, and a widespread refusal of humans to recognise other humans as kin. Lynch champions what he calls “radical empathy” in his writing. This involves stepping into the shoes of those against whom we are likely to feel antipathy. In this case, the call is to feel with illegal immigrants and the dispossessed seeking refuge in a new land.

Told in an uninflected third person — a refreshing change from fashionably unreliable or unchallengeably literal first-person narrators — the themes reflect a curiously bloodless and aestheticised engagement with the inevitability of human suffering. Dialogue is often self-consciously poetic and apart from the Kafkaesque interview Larry has with the GNSB, and Eilish’s experiences with her second son, Bailey, the writing rarely comes alive, the eye-catching phrases (“coins free a trolley,” “meets the smell from the bed”) notwithstanding. Although Cormac McCarthy haunts the verbal flourishes, stream-of-consciousness in the high modernist style is pressed into service to express the mind of Eilish, the rhythm of whose thoughts sculpt the story.

While comparison with Clarissa Dalloway is inevitable, there seems to be more of Synge’s Maurya in Eilish’s implacability and stoic resilience, especially as the microbiologist is obliterated by distilled and angst-ridden motherhood. The single mention of her academics occurs in an early conversation with her father when he reminds her that they “are both scientists.” He continues, “we belong to a tradition but tradition is nothing more than what everyone can agree on […] the NAP is trying to change what you and I call reality, they want to muddy it like water, if you say one thing is another thing and you say it enough times, then it must be so.” Regrettably (and all too humanly), Eilish also forges her own reality inside her grief and keeps telling herself that it is not so, that her husband will return, and she must keep up the pretence of an unaltered family for him to return to.

But we cannot know Eilish like we know Mrs Dalloway. “First Ben to crèche and then the children to school, Molly stepping from the passenger door of the Touran with headphones on while Bailey slams the back door, Eilish watching over her shoulder as he stands pointillist by the glass pulling at his Parka [sic] hood,” run Eilish’s thoughts, entangling with narrative action. Thought points jostle each other, eschewing paragraph and semicolon, but without a robust psychological underdrawing. We are told that Eilish “walks alone in the [sic] Phoenix Park seeking to escape her thoughts but can see only her thoughts before her.” But what exactly are these thoughts? We shall never know. For all the narratorial harping on what happens inside her body, Eilish’s mind is out of our reach and her thoughts, instead of rising viscerally from within, must be met outside in a twilit limbo of muddled impressions. And what a pity it is. Lynch says about Virginia Woolf that at university he “could not understand the fuss.” It would be nice if his book could grow to be as “dear” to readers as he admits Woolf is to him now.