Book: SMOKE AND ASHES: A WRITER’S JOURNEY THROUGH OPIUM’S HIDDEN HISTORIES

Author: Amitav Ghosh

Published by: Fourth Estate

Price: Rs 699

For many reviewers, Amitav Ghosh’s riveting new book is genre-bending as it combines history, fiction, memoir and travel-writing in completely unexpected ways. For me, however, notwithstanding Ghosh’s deft interweaving of multiple narrative genres, Smoke and Ashes is convincingly moored in contemporary scholarly debates on the history and the anthropology of colonialism, capitalism and the making of the modern world. What is remarkable though is that from this scholarly perch, Ghosh is able to tell his story with characteristic elegance and lightness of touch.

For those who’ve read the Ibis trilogy, Ghosh’s interests in the histories of predatory labour and commodity regimes of the colonial trade in Asia are well-known. Smoke and Ashes extends this interest from the Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean islands to China. The actors are the same, European and British trading companies and their native collaborators, but the focus of this book is not on labour regimes but on a single commodity — the opium poppy. Ghosh’s story of the opium poppy begins not with the plant itself but with a meditation on China whose ubiquitous, though paradoxical, presence in his everyday material world, beginning with his morning cup of tea, is overlaid by a surprising absence of it in his mental universe.

His book is a provocation to think why this must be. For Ghosh, the answer to the material presence but discursive absence of Chinese history, culture or thought in the mental universe of the ‘Westernised’, ‘modern’ individual lies in the deeper history of not only Britain’s rapacious opium trade and the wars with that country but also the racialised narratives that the ‘West’ deployed to point to China’s moral vulnerability and susceptibility to opium abuse. The casting of China as willing collaborator rather than victim in the opium trade was a ruse that fed into a larger Western project that sought to contain and erase the historical contributions of the country in the making of our modern world.

Ghosh’s quest for these “Hidden Histories” of opium encourages him to synthesise a whole body of historical writing on the opium trade that has come out in the recent past. He builds on these histories while insisting on the need to look beyond human intervention to the poppy plant itself as an active agent and collaborator in its own propagation, first as medicine and, later, as deadly addictive. Ghosh observes that no other psychoactive substance in the world has had such an enduring alliance with the vulnerabilities of the human body and the mind as the opium poppy. Yet the story of opium use, he argues, cannot be told

from the perspective of ‘demand’ alone. The widening and the deepening market for opium consumption was integrally related to opium’s critical role as a tool of early-19th-century capitalist expansion.

But if opium is, indeed, the hidden secret of the birth of Western capitalist modernity, why is there such a resounding silence around it? Ghosh’s journeys into the heart of this debate lead him to suggest that one of the compelling reasons for the silence around opium in histories of Western modernity is precisely because the private wealth accrued from the opium trade was often channelled into spectacular works of modern philanthropy in the very countries in which it flourished. What is visible from the opium trade in Britain, the United States of America and India are

gigantic infrastructural works and innumerable

cultural and educational institutions. But what remains hidden is the story of unspeakable suffering and devastation.

Smoke and Ashes is structured around two interconnected narrative arcs — one that takes us through the English East India Company’s hidden histories of opium production, trade and the wars with China in the 19th century, and the other that takes us into the contemporary opioid crisis in the US akin to that which struck at the heart of the Qing Empire. What connects the two arcs is not only the story of the poppy plant’s unbounded capacity to mutate and become more lethal in its addictive powers through new modes of propagation and processing but also the continuing recognition of opium as a source of legitimate profit by corporates and their collusive States.

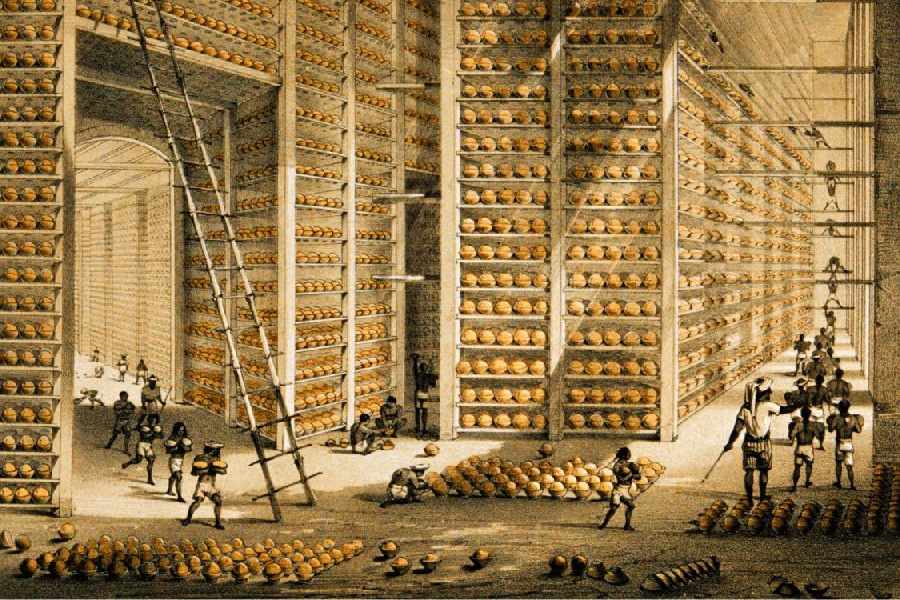

It is these entangled histories of opium and global capital that are woven into Ghosh’s journeys to Ghazipur, the oldest and still surviving opium factory in India, to Guangzhou, where the remains of the Foreign Enclave bear bitter memories of opium’s illicit entry into China but also remain witness to the many gifts that Guangzhou gave to the West: its skills of craftsmanship, botanical knowledge, technical knowhow and a cultural ethos of enlightened cosmopolitanism. As Ghosh takes us through the geographies of opium production and trade, we encounter the impoverished poppy growers of Purvanchal as we do the opium banias of Malwa; we meet the merchant princes of Bombay as we do the Boston Brahmins in the US; we visit the Peabody Museum in Salem as we do the J.J. School of Art in Bombay — only to be reminded that the red line that runs through each of these sites marks the sinuous flow of capital and power that held the opium trade together across continents.

There is a recursive rhythm in the production, sale and consumption of opium that Ghosh dwells on as a cautionary tale of its hold on human lives. Capital’s extractive grip on the poppy plant has always proved elusive; the plant has had a habit of striking back. The contemporary opioid crisis in the US comes as a grim reminder that it is hard to bend the opium poppy to the reckless projects of capitalist greed. It’s time to make peace with it and let it be.