Book: Nomads: The Wanderers Who Shaped Our World

Author: Anthony Sattin

Publisher: John Murray

Price: ₹799

Anthony Sattin presents an alternative history to the usual depictions of civilisation by the Global North that beholds its monuments and art as the epitome of culture. The histories of nomadic people have been ignored by their sedentary brethren. Nomadic oral traditions and their contributions to fostering trade and multicultural diversity, the technological advancements, knowledge dissemination as well as the cultural and political awakenings that they induced make them key figures in global history. Sattin traces the relationship between the nomadic and the settled in a chronological manner over a span of 12,000 years, highlighting the myriad nomadic influences and condensing considerable information into brief accounts, thereby offering an engaging path to tip-toe through history.

Sattin contends that human society has been on the move for most of its history, embodied by the journeys of Noah, Moses, Buddha, Odysseus and Rama. Nomads built the first monuments at Göbekli Tepe in southern Anatolia, tamed the horse and invented chariots, fashioned the composite bow, fought against and reshaped the Egyptian, Greek and Roman empires, before establishing some of the greatest dominions themselves. They admired story-telling and free thought, were tolerant of all beliefs, and accorded women a high position in society. Their need for freedom of movement and open markets changed the world, linking the East and the West, enabled the Renaissance in Europe, while furthering artistic and cultural advances across the globe.

The book first examines nomadic origins, the rise of Mesopotamian walled city-states like the Uruk that altered a communal societal ethos into a more hierarchical structure, and the perpetual tensions between settled and nomadic people along with mutual benefits. This “Balancing Act” reveals how wandering groups, be it the Hyksos, Huns, Xiongnu or Scythians and, later, the Mongols and the Arabs, moving swiftly on horseback, affected kingdoms across Asia, eastern Europe and North Africa, forcing them to regenerate and advance their own civilisations. This cultural inter-mixing resulted in the formulation of the Proto-Indo-European languages from the Pontic Steppes that lend common ancestry to Sanskrit, Greek and Latin.

The “Imperial Act” describes the rise of nomadic power and the cyclical churnings in their own realms. Nomads could create powerful movements but not sustain them once they had settled. Sattin explains how shared religious beliefs enabled nomadic Arabs to reconfigure West Asia’s political landscape, challenge the Byzantine empire and establish Cairo and Baghdad. The formulations of algebra and algorithms occurred thereafter, through the continual exchange of ideas. This Islamic empire was subsumed by Genghis Khan, whose Mongol– Uighur Alliance fashioned the largest pre-colonial empire. Through its trade routes spread inventions like paper, gunpowder and compass into the European realm while Chinese pottery decorated with Persian cobalt-oxide was prized across Eurasia and influenced Dutch and English craftsmen. The emergent riches of the Silk Route induced explorers like Marco Polo to undertake momentous journeys and the nomadic transformation from tent to palace became immortalised in Coleridge’s memorable verse on Kublai Khan’s stately pleasure dome. After the devastating Black Death, Timur refashioned the Central Asian nomadic realm from Samarkand, linking Ming China with VenetianGenoese merchants in a golden age of trade. Their descendants, the Ottoman Turks, would conquer Asia Minor while Neo-Mongols like Babur would establish the Mughal dynasty in India. Although Sattin documents the horrors of the Hun, Mongol and Timurid invasions, he stresses that the affected societies adapted and reorganised to proceed on to greater heights.

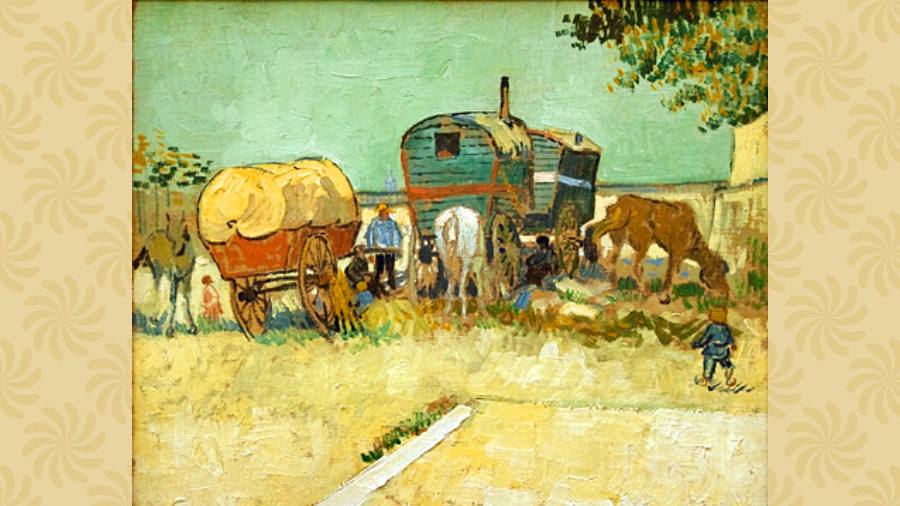

The final section examines the state of nomads in the modern age. It highlights Western scholarly insistence on dominion over nature and the purported manifest destiny of the white man to subjugate other races in the name of furthering civilisation and emancipating ‘barbarians’. This ideology is imbued with prejudice against all who wander and enabled the coercive colonisations in North America and Australia, with the original inhabitants being herded into reservations. Sattin recounts how the Industrial Revolution pushed nomads to the brink by creating factories, extending railroads, furthering urbanisation and consolidating landholdings. Yet, this also gave rise to the feeling that something integral to the human condition was being lost by people having to subsist within urbanscapes without the freedom to wander. This yearning for the outdoors echoes in Thoreau’s writings and was central to the widespread acclaim bestowed on documentaries about Inuit and Kurdish migrations.

Sattin’s Nomads stands out for its lucid portrayal of complex historical threads and its factual, yet nostalgic, undertones. The great importance placed by nomads on free movement is in stark contrast to present-day political borders, the anti-immigration fervour and the occupation of the original nomadic heartland by a superpower intent on expansionist ideologies. Nomads is a reminder that our world was profoundly shaped by people who lived unencumbered, in balance with the natural environment, and that modern society would be wellplaced to follow their guiding principles of tolerance, equality and companionship.