Consider the ubiquity of hunger in the world inhabited by Goopy and Bagha. In Upendrakishore’s tale, the ghosts — kindred spirits — hand over a magical tholi after Goopy and Bagha ask for a boon to escape the pangs of hunger. Some of the other characters in Upendrakishore’s stories appear famished too. Jola devours pithes (“Jola aar saat bhoot”) while Pantaburi cannot have enough of — you guessed it right — pantabhaat (“Pantaburi”); Dukhiram thinks nothing of stealing payesh (“Dukhiram”); a thief suffers for his greed in “Paka Pholar”; as does the fox after mistaking a hive for the sugarcane that he so loves (“Aakher phol”). Perhaps it is pertinent to mention that the Indian famine of 1896-97, in which Bengal was affected, had occurred in Upendrakishore’s lifetime.

Pestilence, that other malevolence haunting Bengal’s countryside, casts its shadow too. Is that why wily Tuntuni decides to approach the mosquito — the harbinger of disease and death — to teach one human, a barber, and many animals a lesson in humility?

Upendrakishore has been credited with opening up the magical world of vernacular, indigenous fairy tales for children. Writers have often employed fantasy as a literary crutch for young minds to escape grim realities. It must be said that Upendrakishore’s ability to gently ease children into the hardships of the world through such surreal, lovable creatures as Goopy and Bagha must count as one of his enduring achievements.

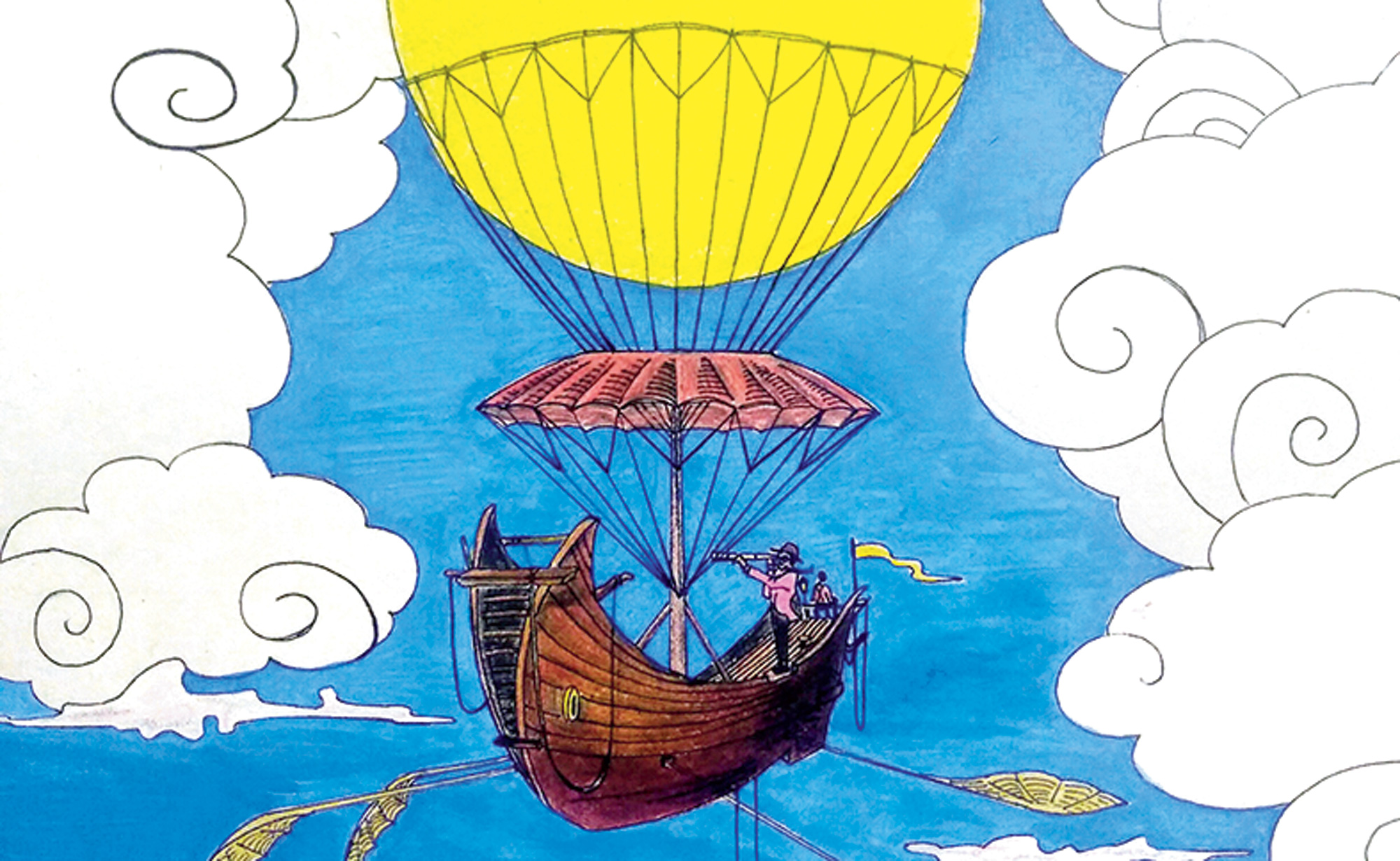

Goopy Gyne and Bagha Byne, contrary to popular perception, have not turned 50. They are one hundred and four years old. Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne, written and illustrated by Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury, first appeared in Sandesh in 1915. Satyajit Ray, Upendrakishore’s grandson, adapted it to make his memorable film in 1969. Therein lies the confusion regarding Goopy and Bagha’s birth certificate.

The original text and its cinematic adaptation vary subtly. For instance, Hallar Raja is a rather benign monarch in Upendrakishore’s version of the story. Satyajit had turned the king into Goopy-Bagha’s principal adversary. But there are continuities between text and, in a manner of speaking, image. This uninterruptedness is important not only because it bears proof of the fidelity between the two productions. The shared elements in the story and the film also go to show that as artists, Upendrakishore and, later, Satyajit were keen on using the genre of fantasy to deliberate on a reality pockmarked with manifestations of social inequities.