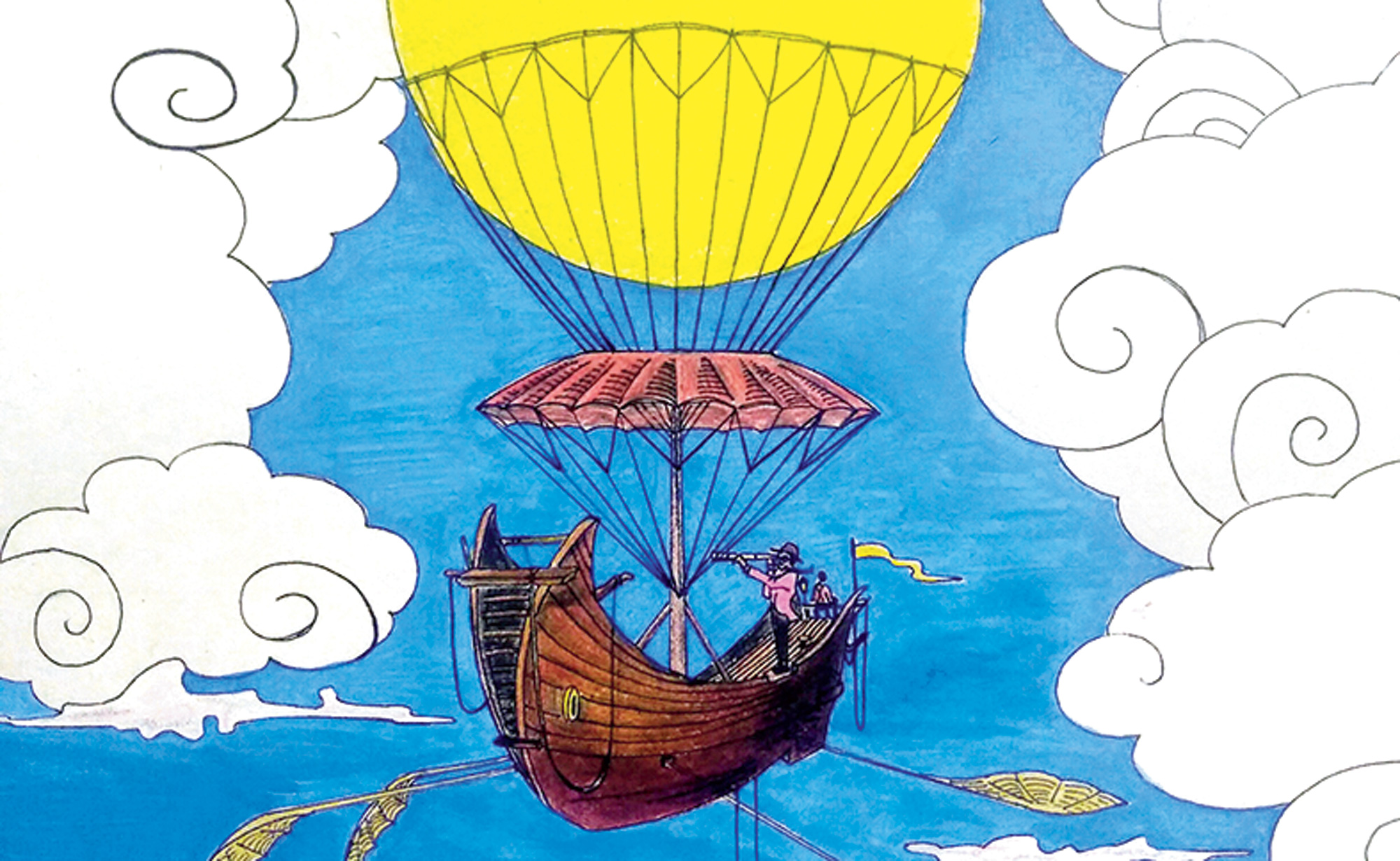

A preternaturally talented slave boy finds salvation in the form of his cruel owner’s brother, Christopher Wilde, a gentleman scientist, who steals Wash from his brother on the ‘Cloud-Cutter’ — a contraption that allows them to sail the skies. This is the beginning of an adventure that takes Wash from Virginia, the Arctic Circle and Nova Scotia to London, Amsterdam and Morocco and introduces him to a spectrum of discoveries — from early forms of scuba diving to miraculous means of recording images — that were transforming lives in the 19th century.

Even though Wilde recognizes and encourages Wash’s skill as an artist and his aptitude for science, and treats him with a kindness that is baffling to someone used only to cruelty, there can be no friendship between them. If brute force had held Wash captive before, it is his indebtedness for being rescued and expectation of love from Wilde that become shackles that he is unable to rid himself of till the very end. Moreover, while Wilde is sympathetic towards Wash, he never treats him as an equal. This adds to the psychological burden of slavery that Wash carries within him even as a Freeman. Yet, Wilde, too, is unfree in a sense, tied to his father and brother by invisible links similar to the ones that tether Wash to him.

Freedom, though, is not Edugyan’s only concern. She also explores the trials, tribulations and concealment of a black genius. Historically, black people have been the subjects of studies, not ones doing the studying. Edugyan challenges this by making Wash — who begins his life in chains and expects to die a slave — a pioneering zoologist who is behind the creation of the world’s first aquarium. But here the plot starts to strain credibility. Wash, a black teenager, bearing the scars of his past on his face, dashes about from country to country — chasing his protector and his dream of building an exhibit of live sea creatures — with the daughter of a white man by his side, facing little to no humiliation. If such a luxury is uncommon in the 21st century, it would have been an impossibility back then.

Wash’s language evolves too — he goes from a boy who, his genius notwithstanding, has much trouble reading to one whose intonation becomes rapidly that of an English gentleman. But the engaging vividness of Edugyan’s prose makes this oversight easy to miss. The pictures she paints with her words evoke dread, melancholy and wonder, transporting readers to faraway worlds.

Washington Black By Esi Edugyan, Serpent’s Tail, Rs 699

“What it like, Kit? Free?” Washington Black, an eleven-year-old slave in Barbados, spends his life seeking the answer to this question that he had once posed to his fellow slave. By naming her protagonist after America’s first president — a man who owned hundreds of slaves while leading his country to freedom on the basis of the belief that all men were entitled to liberty — Esi Edugyan establishes that there are no easy answers to the query. Thus, even though Washington Black, or Wash, declares that he narrates the events of the novel as a Freeman within the first few pages, fetters, both real and imagined, continue to torment him. Edugyan’s enquiries regarding the shifting nature of freedom are neatly tucked into a narrative that reads more like a Jules Verne adventure than a Grand Guignol of slavery.