Book: Kaikeyi

Author: Vaishnavi Patel

Publisher: Hachette

Price: $28

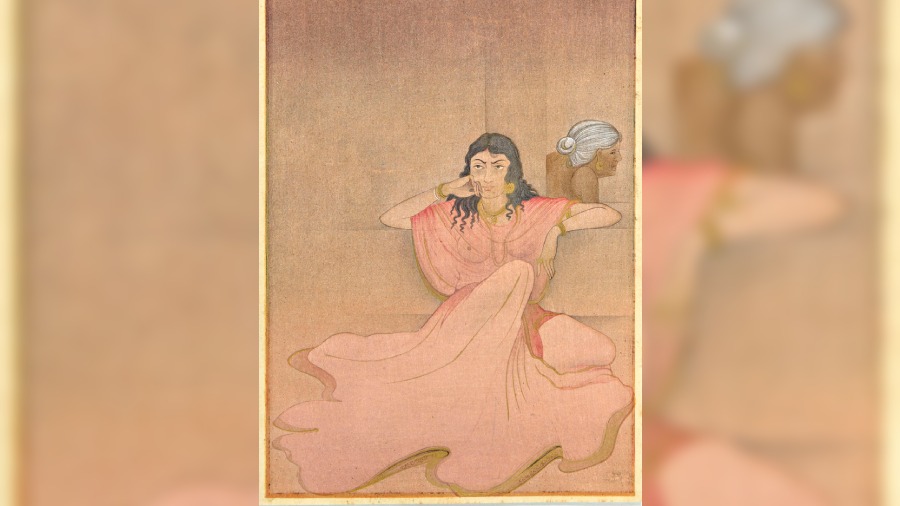

Would you have seen a painting of Kaikeyi by Nandalal Bose? A young woman dressed in finery aplenty and some venom in her eyes. Behind her, an older woman, a hunchback. An outline of a pillar between them, so fine that the two seem soldered. The painting is titled Kaikeyi and Manthara, but it could well have been called Kaikeyi Manthara.

Kaikeyi is no inconsequential figure in the Ramayana and yet, so many interpretations of Ravana and Sita later, she remains a type — the easily swayed queen, the other mother. Is there any one visual you associate with Dasharath’s third wife? I think Kaikeyi, and the mind prompts an image of a Lalita Pawaresque Manthara instead.

The triumph of Vaishnavi Patel’s Kaikeyi is in the giant leap of imagination that is this undertaking. She has me at the book title.

Don’t even begin to reach for this book if your intention is to foreground this version of Ramayana or contest that. This is a novel.

Travel light. Some familiar names, the outline of a story, those should be enough. If you pick it up only because you are surprised that Kaikeyi’s story could fill so many pages, that is a good place to start.

Sita Theke Shuru is the title of one of Nabanita Dev Sen’s books. Meaning, it all begins with Sita. The last line of Patel’s novel reads, “Before this story was Rama’s, it was mine.”

Kaikeyi’s story is told confidently and compellingly.

At the core of the first half is an absence. Kaikeyi’s mother Kekaya disappeared when Kaikeyi was a girl. The mother’s absence, the memory of her and their time together shape Kaikeyi’s personality, feed her accomplishments, determine what kind of woman she will be, what kind of mother, citizen and saciv. It is integral to her ideas of freedom and power and what ends she believes they can achieve. As Patel builds it all up, how Kaikeyi uses these ideas in little and big ways end up contributing to the ready acceptance of the theory of her villainy when Rama is exiled.

For instance, she starts the Women’s Council in Ayodhya. The idea is that the women of the palace should lend ear and help to regular womenfolk. Kaushalya and Kaikeyi modify grain storage quotas to distribute food to children on the streets, and Sumitra employs homeless women in the palace kitchens. But the men of Ayodhya resent the council for drawing the women out of their homes and by association they dislike Kaikeyi.

The telling is full of little touches that make Kaikeyi very relatable. At Sita and Rama’s wedding, Kaikeyi is enjoying herself. Suddenly, her thoughts turn to Janak. Patel writes: “I imagined the palace at Mithila would seem quiet… and I was sad for him.”

Then there is her relationship with Manthara. Kaikeyi is briefly reunited with Kekaya at a later date; but when Kekaya caresses her, Kaikeyi feels guilty. Patel writes: “… it felt like a betrayal of Manthara.” Such detailing chips away at givens and absolutes, prepares the ground for a new rationale to a foregone conclusion.

Also running through the book are the notions of free will and godhood. Kaikeyi is “gods-touched”, which means just the opposite of what it sounds like, basically forsaken by the gods. It gives her certain powers, lends her a certain immunity, but the gods don’t listen to her prayers. The reader is left to work out what this really means in comparison to Ram’s unconflicted but imperfect godhood.

My sole quibble is with the idiom. Patel says in the Introduction that she does not seek to replicate the world, technology, or customs of any exact time period or civilisation in South Asia. I suppose she means the same logic to extend to the idiom as well.

But the idiom is the chariot of the narrative. And the imaginative feat here needs the chariot to do more than not collapse under the weight of a dramatic telling. It needs it to fly.

Also, it is one thing to make characters out of an ancient epic relatable, but if you leaven every difference you hack at the USP of the book — a new way of looking at an accepted story. And what better way of conveying that difference, without compromising effect, than fitting idiom?

William Radice writes that after Michael Madhusudan Dutt finished writing Meghanad-badh Kabya — a topical ancestor of Kaikeyi — he summed up his effort with a sloka that read: “Sariram va patayeyam karyyam va sadhayeyam.” Radice, who writes about Madhusudan’s linguistic achievement and audacity, translates it thus: “I would rather die than fail to achieve what I have set out to do.”

I very much look forward to Patel’s next book.