CIRCLES OF FREEDOM: FRIENDSHIP, LOVE, AND LOYALTY IN THE INDIAN NATIONAL STRUGGLE

By T.C.A Raghavan

Juggernaut, Rs 799

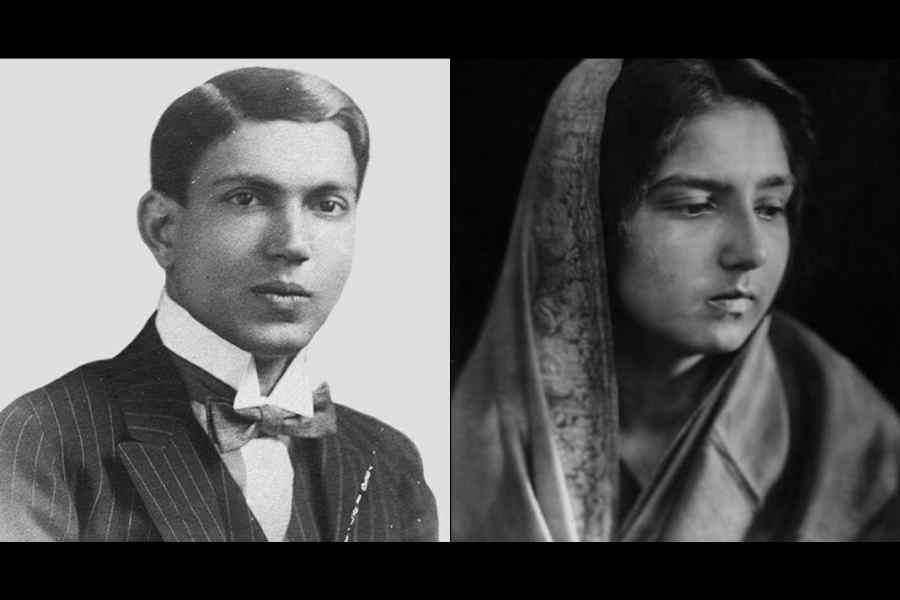

As the amritkaal progresses into an uncertain future, the memories of some long-forgotten freedom fighters are brought to the fore by T.C.A. Raghavan in his new book. In particular, it explores the lives and the times of the barrister, Asaf Ali (picture, left), and his circle of friends: Sarojini Naidu, her brother, “Chatto”, Syud Hossain, Syed Mahmud, and Aruna Asaf Ali (picture, right). And it gently reminds us of certain legacies that have survived instead of their visions of the future.

Asaf Ali was a quiet but steadfast believer in the Swarajist politics of C.R. Das and Motilal Nehru. He thought of a decentralised “Commonwealth of India”, which led to strong disagreements with Vallabhbhai Patel and J.B. Kripalini while they were incarcerated during the Quit India movement. In a way, this book is also about Asaf’s predicament and legacy — an Anglophile young man who studied in London but turned nationalist, a Western-educated, moderate Muslim viewed with suspicion by Hindu peers and as a renegade by Muslim hardliners.

Asaf’s 1928 marriage to Aruna Gangulee further fuelled communal rancour. A contemporary English newspaper made a headline of their marriage:

“Mohammadan to Marry a Hindu Girl”. The next day, another newspaper published a large studio photograph of Aruna seated on a chair. Impropriety in news reporting, too, has a long history.

Central to Raghavan’s telling is the changing nature of Asaf’s relationship with Aruna. She emerged as a firebrand leader during the 1940s, championing revolutionary change over Swarajist constitutionalism, which formed the bedrock of Asaf’s belief system. Seven months into their marriage, both were eyewitnesses to a landmark event of the freedom struggle: Bhagat Singh and B.K. Dutta’s propaganda of the deed at the Central Legislature. Asaf served as Singh’s defence lawyer. Later, he was part of the lawyers’ team that defended the INA prisoners.

For Asaf, revolutionary action was reckless — he held that Quit India was a rash move, which provided the colonial government and the Muslim League the power to press for Partition. For Aruna, however, August 1942 was the unmistakable pinnacle of the freedom struggle, the defining moment when forsaking narrow religiosities “(t)he Indian came nearest to perfection.” Working underground, she supported the ratings of the Indian Naval Mutiny in 1946 and found herself in league with a group of Congress socialists — J.P. Narayan, Ram Manohar Lohia and Achyut Patwardhan, the iconic leaders of post-Independence India.

Their relationship deteriorated irreconcilably. However, when Asaf died in Berne in 1953 — a few months after his appointment as ambassador to Switzerland — Aruna was at his side. A lifelong and austere adherent to secular and socialist ideals, Aruna did not choose a career in politics. She returned to journalism in the 1950s, founding the Left-leaning weekly, Link, and, later, a daily newspaper, The Patriot.

The book leaves its readers thinking of the lasting legacy of communal violence in India. Long before the Partition — following M.K. Gandhi’s withdrawal of the Non-Cooperation Movement and the military quelling of the Mappila uprising, which later took on a communal colour — riots spread and intensified across British India. If the need of religious figures to proselytise and mobilise support for elections to the provincial assemblies was at work — therefore the strategic deployment of words like sangathan and tanzeem — the onus was equally on the colonial ‘free press’. Raghavan draws our attention to a letter written by a worried Asaf to Gandhi in which he refers to how insidious news reports cite “every street brawl” as a communal flare-up where “every worthless delinquent who bears a Hindu or Muslim name is held up as a type of civilization which each name is supposed to represent.”

In the face of this violence, frustration and incomprehension appeared widespread. But Raghavan notes that these riots also shaped a countervailing legacy. In response to Syed Mahmud’s letter detailing his troubles in restoring amity in Bihar, Jawaharlal Nehru replied: “I am more and more inclined to think that the only remedy is to scotch our so-called religion and secularize our intelligentsia at least. How long it will take I cannot say, but religion in India will kill that country and its people if it is not subdued.”

Almost a century later, Nehru’s words can be aptly described as prophetic.