Book: Dethroned : Patel, Menon and The Integration of Princely India

Author: John Zubrzycki

Publication: Juggernaut

Price: Rs 799

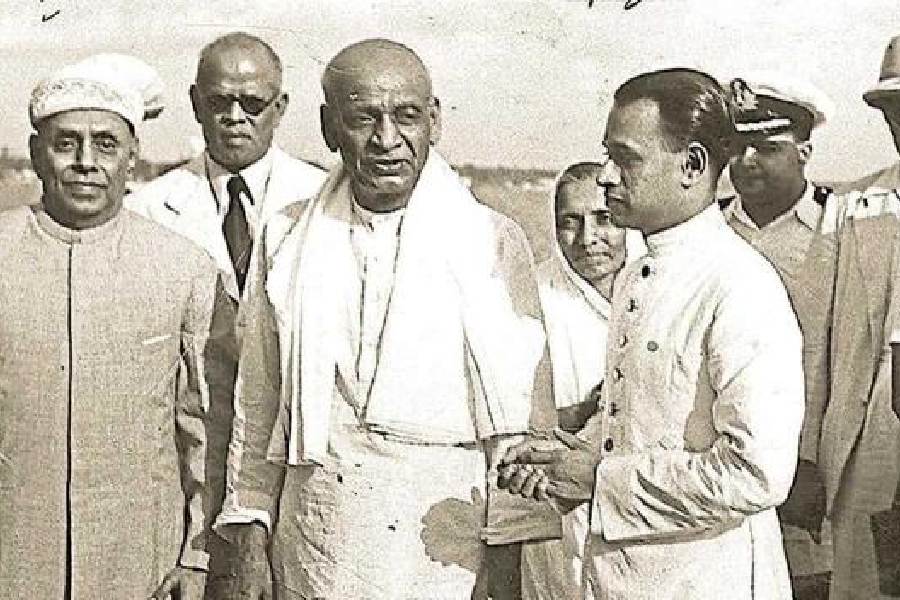

It is a truth universally acknowledged in India — especially in the post-Statue of Unity India — that Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, popularly known as the ‘Iron Man’, was the chief architect of modern India as we know it. In Dethroned, John Zubrzycki tells the story of how Patel and his aide in the department of states, the “diminutive” V.P. Menon, steadily shepherded the multitudinous dynasts to come round to the plan of accession with the Indian Union.

The sheer number of princely states, which comprised the territories of the modern nations of India and Pakistan, is likely to astound the lay reader. As Louis Mountbatten disembarked in the sweltering heat of Delhi in March 1947, more than 550 States were scattered across the subcontinent, varying in size and monetary wealth — from a rajah ruling over a few square kilometres, sharing the ground floor of his ‘mansion’ with his cattle, to the fabulously wealthy Nizam of Hyderabad, who famously refused to be cowed either by Jawaharlal Nehru or Patel and decided — fatefully — to maintain an independent Islamic potentate deep within the heart of the Deccan.

Readers who might think that this book is simply another one in a long line of literary works on the integration of princely states would be assured to know that Zubrzycki covers more ground than some scholarly works, like Ian Copland’s The Princes of India in the Endgame of Empire: 1917-1947, did, stretching the narrative into three parts — how the rulers in the states were convinced to sign away their paramountcy, how the scattering of principalities was gathered together to form provinces resembling India’s current political map and, finally, how, in one fell swoop, Indira Gandhi amended the Constitution in 1971 to wrest away the privileges and privy purses from royal hands. The anecdotes about jostlings for primacy on the royal hierarchy — which prince would get the larger privy purse, who would get to keep their mansions and their collections of Rolls-Royce cars — are engaging. Where the book falls short is in its one-sided deification of Patel and Menon, relegating Nehru to a blustering, pompous politician without an iota of tact and diplomacy. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, predictably, remains a scheming mendicant, focused more on India’s destruction than on Pakistan’s construction.

At a meeting with Mountbatten sometime in the weeks before August 15, 1947, Patel proclaimed that the only condition under which the proposed plan for dividing the subcontinent into two dominions would be accepted was if the viceroy himself delivered a “full basket of apples” — convinced all 565 kingdoms to join India. Mountbatten’s retort was to ask if he would accept 560 states instead of the full basket. When one thinks about the eventual incorporation of the princely states into India, the forceful invasion of Hyderabad and the arm-twisting of the rulers of Junagadh and Kashmir come to mind. But Zubrzycki’s account reveals how a large part of the process simply entailed haggling like fruit vendors in the corridors of power.