Recap: Molly’s wedding becomes the point of convergence of old friends and the occasion to make new ones as Vik, Tilo, Aaduri, Ronny, Goopy, Duma and Pragya, among others, mingle. Lata slips into the empty anteroom, where Ronny finds her poring over her phone.

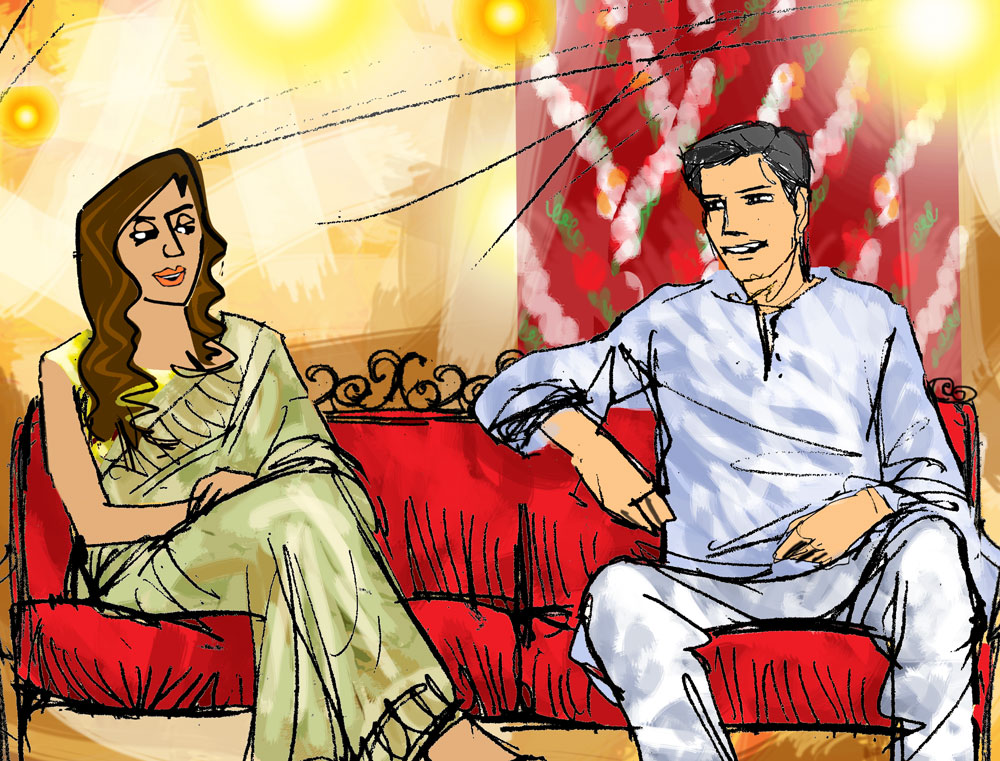

Molly’s wedding, the Oberoi Grand, the end of an era. If this were not life but a film — not the kind of serious film Ronny Banerjee made, of course, but the sort of romcom Lata watched on cold London nights — then this would be the moment when a nostalgic melody from the past would cue in, and under the soft warm glow of the single chandelier in the antechamber, on that plush sofa scattered with flowers that Molly’s garland had shed, Lata Ghosh and Ronny Banerjee would speak of the years gone by, of love and mistakes and second chances.

But this being life and not cinema, romantic music is replaced by the background hum of the banquet hall. The Ghoshes and Jaiswals mingling with the Bansals and Boses, chomping, laughing, comparing, balancing social vengeance with the bonhomie of new beginnings.

“Does your new friend bite?” Ronny asked.

“Does yours?”

Lata’s voice had darkened with something. Not quite jealousy. But something like it, viscous, lurking with shadows.

“No,” said Ronny, after a beat, “she doesn’t.”

“Mine doesn’t either,” said Lata, smiling in relief, “But, as it happens, my new friend has a new friend who might bite.”

“That sounds like a riddle,” said Ronny, impatient to get to the bottom of this business, “Who is your new friend, Charulata Ghosh?”

“Why do you care, Shomiron Banerjee? I thought you had at least a decade and a half to recover from your insane jealousy.”

“I don’t know what you are talking about. I am not the one who suffered from insane jealousy even though I should have. Every single time I called on the landline, in your hostel at IIM-C, you were out. There was always group work, projects, etc., etc. And every time you came home, you just sat down in your room and studied like a bloody nerd. Why do you think Molly and I got so good at carrom in those months? Yet, if you remember correctly, jealousy was never my thing. It was yours.”

“Oh please!” exclaimed Lata, her voice, which had been velvet with irony all this while, now animated with angry sparks.

“Of course. Just because I spent all summer directing that play I wrote. Wait, what was it called?”

“The Ex,” Lata supplied, despite herself.

“The Ex! Right! I had been so pleased with that title,” Ronny burst into laughter.

“And how apposite it turned out to be,” Lata smiled, the voice reverting to velvet.

“You were doing an internship that summer, Charu. You had no time. But you used to get so mad at me because I was obsessing over that stupid play. You know how tyrannical I get when I am in director mode.”

“You were spending far too much time with your leading lady, Ronny. Now, her name I can’t seem to remember. But as we can see, the habit has stuck. Obviously, I was some sort of a clairvoyant.”

“That’s utter nonsense. Both my previous leading ladies were happily married. And none of my other partners have had anything to do with the film world. Also, just a point of note, I never loved that Moyna Mitter from ISI. I didn’t even like her that much. I was, if I remember correctly, madly in love with you, Ms Ghosh.”

“That’s too many ‘loves’ in one sentence, Mr Banerjee. I have lived in cold England for far too long where we don’t bandy about that word, and, as it happens, I have parsed the fine differences of love and like and in love for decades. Anyway, let’s not muck about in purono kasundi. The others must be waiting.”

Lata got up and adjusted the pleats of her sari unselfconsciously, shook out her aanchal, which fell in a golden swoon upon the air. Ronny did not get up.

“You are probably going to meet my new friend in Jamshedpur. She is Pixie, eight years old, Bappa’s daughter.”

“Bappaditya from Statistics?”

“The one. Pixie has acquired a puppy called Scone.” Lata handed him her phone where a photograph of a cute polka-dotted puppy had just downloaded. Ronny looked at it blankly. “Riddle solved? I’d better go and oversee stuff now. I’ll see you around.”

Ronny didn’t get up or follow her out. After a moment or two, muscle memory asserted itself. It was his turn now to check his notifications.

There was nothing from the Maheshwaris, though. However, a slew of texts from Pragya. He typed, “I’m coming in a minute”, but made no effort to move.

Of course he’d been insanely jealous, when Lata had brandished that handsome Aarjoe she’d met at her campus placement — who meets their future husband at a campus interview? How can it ever end well? — with his prospects and his cars and his fine suits. “The only reason you’re marrying him,” he’d told her in a black mood, when it was already too late, when Ghosh Mansion was already strung with lights and guests had already begun to arrive, “Because you are, at heart, a hypocrite. Just as your ancestors had built this grand house in collusion with the British, you are going to collude with global capitalists. You have no respect for either knowledge or art. You are basically trading up. You think I am a dabbler, like your father was. Dabbling in art. Maybe I am. But maybe I am not. Maybe I shall be a great filmmaker after all.”

“I do hope you become a great filmmaker, Ronny,” Lata had said, simply, after that outburst, meaning every word.

“I hope you are happy,” Ronny had replied, not meaning it at all. He’d hoped she would be bitterly unhappy all her life.

***

By 11, most of the guests had left or were just taking their leave. None of the ladies had liked to burden their five-star fashion statements with sweaters and coats — after all, if you lived in Calcutta, you didn’t really invest too much in beautiful warm clothes since winter was so brief — and so, half-regretting that fact, they decided to leave early, before the night got too cold. In any case, tomorrow was a weekday.

The Ghosh elders, now sitting in a glut by the door, looked exhausted. Boro Jethu had his feet up. (One of the waiters had found him a footstool.) The Jaiswal patriarch had been bundled home a couple of hours ago, and AJ’s parents were now thanking Bobby for her magic touch. Earlier, they had sought Lata out and thanked her too. The bride and groom, surrounded by their friends and the few cousins close in age, were laughing over dinner. They would soon retire upstairs, where a little room had been booked for the after-party. They were calling it the basar of course. Lata and Goopy had excused themselves from this shindig, they were too old for such things. They would return to Ghosh Mansion where, tomorrow, a final lunch had been organised, after the vidai. The Bongs had got their basar and kal ratri, the Jaiswals had got their sangeet and vidai. And Boro Jethu had had the last laugh. Tomorrow’s lunch, after the Jaiswals left with Molly, would have both mutton and fish.

At the other end of the banquet hall, Tilo’s table, though, was going strong. Tilo’s mood had rapidly improved after she’d found out that Goopy and Duma could become great contacts for the future, and now she sat between them, chattering nineteen to the dozen. Ronny sat next to Pragya and gossiped endlessly with Duma — a conversation that flourished like an underwater stream just below the expansive saga spun by Tilo. Lata was finishing dinner. She silently observed Aaduri polishing off Hem’s rabri.

“Hope you have Harry Belafonte ready, Lata?” Vik asked, spotting a lull in his wife’s rhetoric, “Molly and AJ seem to be leaving...”

Lata looked genuinely mystified.

“Oh hahahaha, I got it, I got it,” Hem said ebulliently. He turned to Lata, “Charulataji, thanks to you, I am now an expert in chao questions. The answer is Jamaica Farewell. Or jamai-ka farewell.”

Everyone laughed. Once again, Lata wondered at the tinkly, wind-chimey sounds that emerged from Pragya’s reed-like form. “How could Ronny bear this sound? And why was she still here? Hadn’t she been in a rush to leave?”

“Now, here’s one for you lot,” Hem said, “What were the Ghosh relatives and friends singing on the day of Molly’s sangeet?”

“Meat na-a-a-a-a mila re man-ka...,” sang Ronny, tunefully. Pragya shot him a besotted look.

At that exact moment, Lata looked at Aaduri. Aaduri rolled her eyes. And suddenly, the ridiculousness of it all hit Lata. She began to laugh, and, soon, everyone had joined in. From a distance, when Manjulika saw them, it seemed they’d regressed back into the past when the future had stretched out endlessly in front of them all, covered with stardust, and they were each certain they would live forever and choose the lives they wanted.

(To be continued)