Recap: Back from New Town and sitting on a bench in the little neighbourhood park, Lata replies to Pixie’s email. But as she is jauntily walking home afterwards, she stops in her tracks as she sees Goopy, who had been away for 12 years, get out of a cab in front of Ghosh Mansion.

Goopy stared at the poster of Bob Dylan on the wall. Lata chewed her lips. Without intending to in the least, in the bare few minutes that had passed since Goopy’s return to Ghosh Mansion, the cousins had slipped into old patterns. From the window that Raju had thrown open, sunlight now poured onto the white bedcover, a golden rectangle, interrupted, albeit elegantly, by the iron bars of the window. How Lata used to envy him his en suite, she now remembered, as she stretched her toes into the patch of sun on the bed and allowed her feet to toast in its gentle warmth.

“No actually, haven’t come alone,” Goopy finally laid out the facts, in gentle leaps, “Duma is here too, we landed this morning.”

“Where have you tucked him away?” Lata asked, raising her eyebrows and rounding her eyes.

Goopy turned to her and smiled his lop-sided smile. “I checked him into a hotel. I mean, we went to the hotel first, he checked in, I left, I suspect he is now stuffing his face with whatever’s on the room service menu.”

“That’s horrible, Goopy!”

“Calm down, Munni,” Goopy said, “You may have spent a year or two in the West.”

“Fifteen,” Lata rolled her eyes, though she could see that he was horsing around.

“And you may have befriended the token fey here and there, a diversity candidate or two.”

Lata now composed her features into her well-practised I-am-not-going-to-stoop-to-reply-to-your-accusation-that-I-work-hard-at-polishing-my-liberal-credentials-even-though-I-suspect-it-might-be-true face.

“But,” said Goopy, now walking up to her and flicking her nose lightly, “Charulata Ghosh, you have no idea of the protocol involved in bringing an ‘unsuitable’ man home. At my age. From my end of the gender continuum. In Calcutta. Not that you’d know. You’ve never brought home any suitable ones either. Except Ronny, that is.”

“Never did you once tell me, in the ancient past when Ronny Banerjee was in and out of this house like all the time, that you thought, for a second, he was a suitable boy,” Lata now stood up to hold open the door as Nimki entered with a tray: tea-things, Manjulika’s precious porcelain, the works.

“Is AJ a suitable boy?” Goopy asked her, seriously.

“I really think he is. Molly’s chosen well.”

“I do think we Ghoshes need an encounter or two with ‘The Other’. He is Marwari?”

“Jaiswals are technically not Marwaris or so I have been told,” Lata clarified. “But there is some dispute. Sane family, though.”

“Oh good. Since ours is off the rocker, sanity is desirable.”

Goopy lifted the lid of the chipped blue bowl as Nimki’s tray floated into range. “Marzipan bites! Nahoum’s?” He picked a pink one and popped it into his mouth.

“Aaduri got them,” said Lata, taking over the tray and placing it on the bed.

“Na, Hem brought them,” Nimki corrected her, “Uff, Boro Boudi! Not a single table is free,” she muttered, “No place for the tray.”

It was true. Twelve years was a long time to allow the flat surfaces of an empty room to remain unoccupied. The bed, posters, guitars, cassettes, the tape deck: all there, of course, constituting the bare outline of what was recognisably Goopy’s room, but distributed into it were several kilos of objects that had leaked out from the rest of the house.

“Let me pour the tea, Mamoni,” Nimki offered, “I know you both have to do everything in those places — London, America, wherever — but here...”

As Nimki waved about her hands to indicate those far-off, possibly not-worth-the-fuss places, Goopy came and gave her a hug. “Oh-ho, stop, now I’ll slop tea on that bedcover!” she complained, cheeks pink with all the attention. “It is the last one your grandmother had crocheted, and her ghost will come and give me a tight slap if I stain it accidentally. Don’t make a face, Munni. Ghosts do slap people. Don’t stuff yourself. There’s lunch.”

“Don’t worry,” said Lata now helping herself to cheese biscuits, “We’ll have lunch after we come back. None of the others are getting home before three it seems.”

“Going out again? Do what you want,” Nimki said, withdrawing, “Just don’t ruin that bedcover.”

“It’s already become cold, Munni,” Goopy said, sipping the tea. “No surprise, given the distance it has travelled. So where are we going?”

“To check out the room-service menu, of course,” Lata replied.

***

“They cancelled,” Bobby looked up from her phone.

“What?” Ronny was putting finishing touches on the presentation that Bobby had put together last night — god knows when she’d had the time — adding a sentence here, deleting a word or two there, appreciating the clarity of thought at one place, getting maddened by the lack of nuance in another.

“Nikhil’s office has just sent an email. They can’t meet us this evening.”

Ronny continued to tinker with the slide.

“They want to reschedule. Tomorrow’s obviously out. How about later this week?”

Bobby had begun to furiously circle the bed, phone in hand, her yellow cape swishing. Like a tigress, Ronny thought.

“Let’s wait for them to suggest an alternative date, Bobby.”

She now stopped moving and came and sat next to him annoyedly. “Let me remind you Ronnyda, the need is ours.”

“Calm down,” said Ronny, moving onto the next slide, “I had an inkling this might happen. Go get the newspaper, the Chennai edition, it’s in the drawing room. Baba reads it after me.”

“Can’t you just tell me?”

“It’ll take a minute.”

“Fine,” said Bobby, with bad grace, and her heels tap-tapped on the mosaic as she made her way out.

***

“Kenneth Atieno,” the tall man broke into a smile when he opened the door to Lata, “but everyone calls me Duma.”

Tall, check. Muscles, check. Skin, the colour of 70 per cent dark hot chocolate, check.

Damn, her cousins were all getting their act together, Lata thought, supremely jealous for an instant.

“You are an honorary Bengali already then,” she said, smiling, extending her hand towards Duma. “All Bengalis have a good name. And a nickname. My rude, almost uncivilised cousin who left you here while gallivanting home is called Goopy in these parts.”

“And you must be Munni,” Duma drew Lata inside warmly, “Charulata. The family beauty. And brains.”

Lata laughed. “La-taa now,” she enunciated, “the dental t. What does Duma mean?”

“Cheetah,” he said, adding softly, “I chose it myself.”

Goopy stayed suspiciously quiet through this exchange. He went inside and perched himself at the edge of the bed, checking the notifications on his phone with a grave face.

Lata followed Duma into the adjoining living area, all plush sofas and mood lights, where a cricket match was playing on television. “Goopy surmised you’d be stuffing your face. But I can see your drug is different.”

Duma laughed — he had a delicious, easy laugh, that animated his eyes — as he hunted around for the remote. “Growing up in Kenya, a whole generation of us worshipped Tendulkar and, later, Sourav Ganguly. The first thing that pops into my head when I think of Calcutta is Eden Gardens.”

He found the remote and switched the television off.

“I suppose we can watch one at Eden after Molly’s wedding. I’m sure IPL will be on,” Lata said, “Or something else. Given how obsessed we are with cricket.”

“I’d like that,” said Duma, eyes shining like a kid’s.

“Of course, I gave up on cricket when Hansie Cronje broke my heart. Little did I know then that that’s what handsome men do. Except you, Duma, I hope,” Lata’s eyes danced in mirth.

“Why have you been hiding her all these years?” Duma looked back and asked Goopy. There was no response. “Come join us here,” Duma called again. “Shall we order lunch, Munni?”

“No, no, we are all going to have lunch at home. I am here to escort you to Ghosh Mansion myself.”

“I still don’t think it’s a good idea,” said Goopy.

“Oh shut up, you,” said Lata good-naturedly, “I am quite sure the Cheetah is up to facing a few Bengali aunts and uncles. No guns, only words. And lots of mutton curry and rice.”

“That settles it,” said Duma, “I can even risk a bullet or two in the quest for the Indian goat curry. With potatoes. Right?”

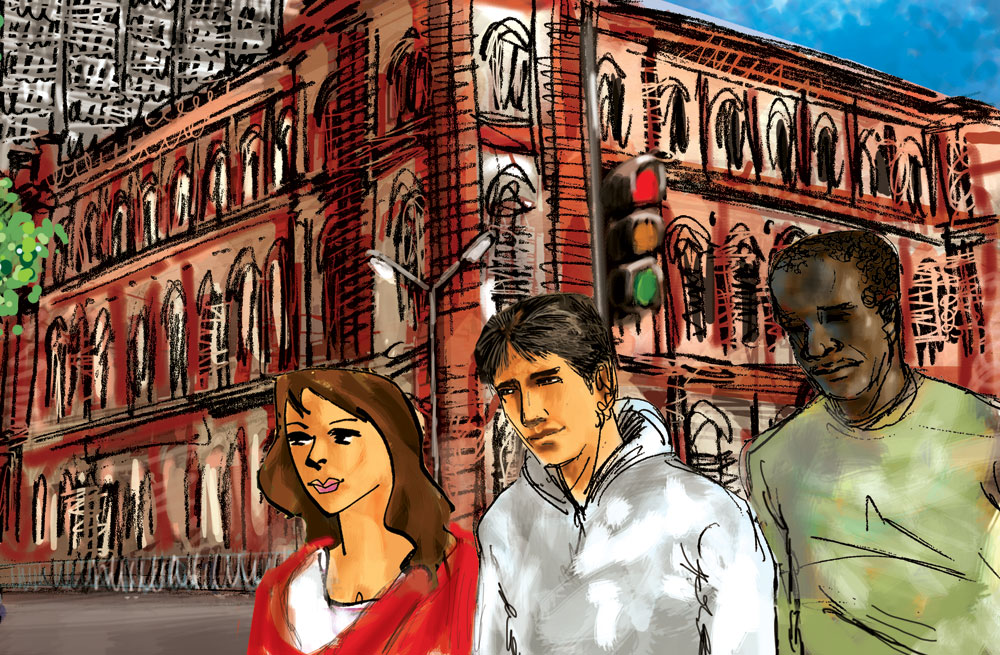

And so it came to be that Duma and Lata and the reluctant Goopy stepped out on Park Street, into the glorious December afternoon in Calcutta, a city that pulls off winter like an old lady wears her prize jewels, elegantly, but with a touch of nostalgia. The sun was so mellow and the nip in the air so piquant, that it seemed as though the unlikely trio would stand there forever, at the corner, by Trincas, waiting for their cab, and the city would reabsorb them into her innards, so they would be enveloped by safety and love and happiness and youth.

Then the cab came, they stepped in, and the doubts returned.

(To be continued)