THE LITTLE LIAR

By Mitch Albom

Sphere, Rs 599

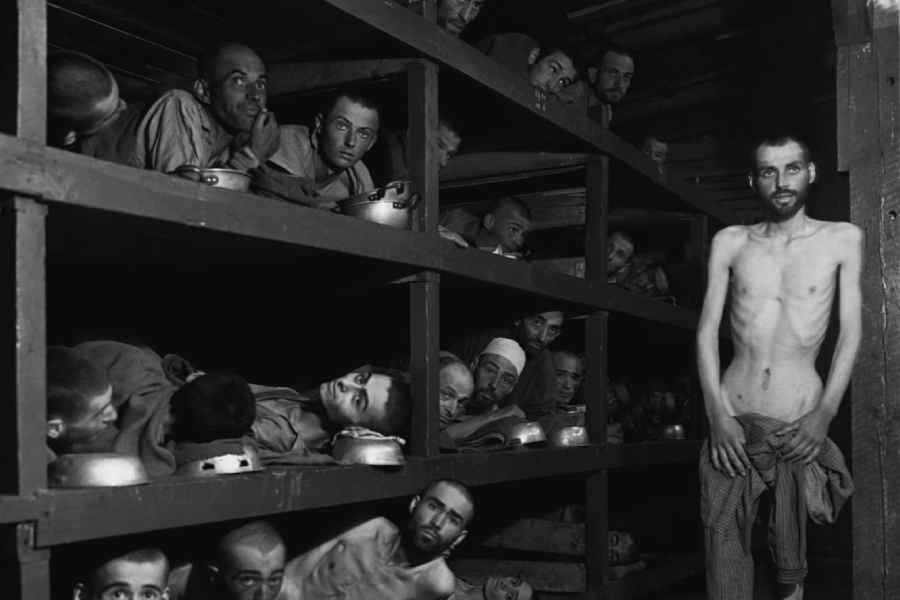

History has perpetrated, harboured and witnessed multiple catastrophes; but only a few have shaken the world as much as the Jewish Holocaust. Mitch Albom travels back to a lesser-known but just as devastated site of this atrocity — Salonika (Thessaloniki), Greece — where 11-year-old Nico Krispis, who has never told a lie, is immune to the treacheries of the world around him. To his honest and innocent mind, the war against Italy has been won and the Germans would do no harm; except that his mother tells him not to trust the men in uniform. His brother, Sebastian, envies his honesty, and the admiration it earns him at home and from their beautiful friend, Fannie. Soon,

the lives of these three children, their families and the entire community crumble down as the Germans invade, humiliate, isolate and strip the Jews of their businesses, faith, property, and dignity before deporting them to an extermination camp in Auschwitz. Nico bears the guilt of setting this evil plan in motion, carrying the message of promising new homes and jobs awaiting at the other end of the journey, unwittingly falling for what Udo Graf, a high-ranking German officer, believes is a genius trap worthy of a promotion by none other than the “Wolf”, Adolf Hitler.

The author of Tuesdays with Morrie takes a turn from his usual philosophy of finding and doing good in life — especially in the face of adversity — in his ninth novel. While still set in inspiring parables, and in the virtues of truth and redemption, Albom goes the extra mile to write “a story of consequence”. Here, the past has a beginning but no clear end. For those who survive the genocide, the horrors may have ended but it is only the beginning of a lifetime of haunting; Salonika has become “a city of ghosts” where the “lucky” Jews must find a way to survive. Decades later, the three children find their own ways, bound by a string of common fate. Nico abandons truth (but not its morality) and lives from “lie to lie”; Sebastian, understandably, becomes obsessed with the war’s miscreants and dedicates his life to hunting them down; Fannie travels back to places and people in the hope of finding some peace and closure, while Udo Graf, living in disguise, waits to rise again for the Nazi cause.

‘Truth’ is the spokesperson for the characters, an offbeat narrator bearing semblance to another Holocaust story by another unusual narrator, Death, in The Book Thief by Markus Zusak. Even without internal dialogue, the readers know exactly how the characters are feeling and what they are thinking. The segues, too, are stitched smoothly, across characters and the decades between them. The hurried resolution of the years of agony between Sebastian and Nico and the absolution of the jealousy that shaped not just Sebastian’s childhood but also his adulthood are perhaps the only weak links in the story.

What sets The Little Liar apart is how it not only talks about the life at the concentration camp but also the life around and after it. Albom’s characters live with the burden of the past and navigate a future almost empty-handed. This may be his way of paying his due to his Jewish ancestry. Albom adds value to his writing by referring to historical figures like the Hungarian actress/activist, Katalin Karády, the Nazi Hunter, Simon Wiesenthal, the historical White Tower, a symbol of redemption, Hitler’s isolating childhood and the Nazi killings of the Romanian Gypsies.

Like other books on this subject, there is a looming sense of reality as one reads The Little Liar; an awareness that these are real, lived stories of an unimaginable, persistent trauma. Even after 80 years, the vow of ‘Never Again’ is but a taunting, fading resolution as is evident from the sufferings of civilians, especially children and minorities, in Palestine, Ukraine and Central Africa. Albom’s book is but one reminder of what a war does and a request for not repeating it.