In the Introduction of the book ‘Bad’ Women of Bombay Films: Studies in Desire and Anxiety, the editors, Saswati Sengupta, Shampa Roy and Sharmila Purkayastha explain that the “bad” women in the volume “illuminate the desires and anxieties that society needs to police, marginalize and repress”. Far from being simple, this conflict is deeply nuanced and complicated, as the Introduction indicates. It also suggests that the representations of female desire, “plural and mutating yet typified and structured”, through one hundred years of Hindi film cannot be adequately discussed by a “clutch” of essays: this volume is just a beginning. The claim is modest. One of the most impressive features of ‘Bad’ Women of Bombay Films is its thoroughness — of conception, arrangement and reach, of the research that precedes the essays, and of the references and cited works. Although women-centric, the volume can be rewardingly used for any serious study of Hindi films in particular and Indian films in general, having taken birth, the Acknowledgments tells us, from a discussion among teachers of Miranda House about the possibility of a book tracing the history of desire and anxiety underlying the cinematic representation of the modern Indian woman.

Since the essays examine women who can be seen as ‘bad’ or disruptive at different times in different ways, the book looks at disconcerting figures from the 1940s right down to the present, drawing into its scrutiny the undaunted lover, the rebellious wife, the mean mother-in-law, the sex worker, the murderer, the accomplished courtesan, the actor, the terrorist, the avenger and numerous others. The patriarchy they are pitted against, which they negotiate and manipulate as much as it disciplines and punishes them, alters through the years just as the lineaments of the New Indian Woman change through time.

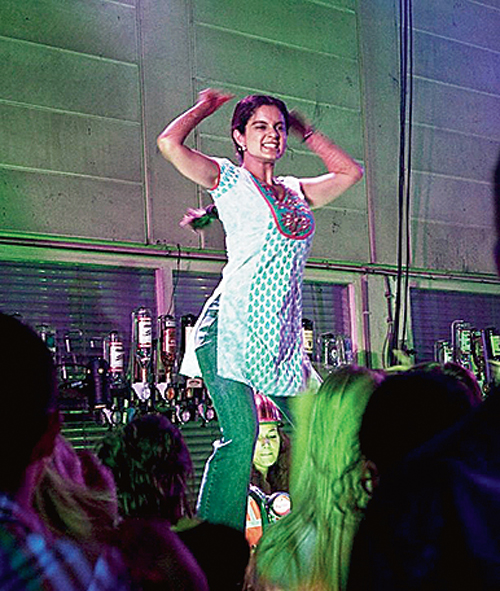

The essays are divided into five sections. Part I is about “The Disorderly Presence at Home” that includes, among others, Ira Bhaskar’s analyses of Achhut Kanya, Tarana and renderings of the Heer-Ranjha legend and Mrinal Pande’s discussion of the evolution of the mother-in-law in Bombay films, while the other essays look at Saheb, Bibi Aur Ghulam and Omkara. The richness of the anthology makes a quick summary impossible. Bhaskar, for example, shows how a film’s songs articulate the excess of emotion, irrepressible desire and unquenchable longing both erotic and spiritual that drives the film’s action but remains unaccommodated in its moral-social framework. Pande’s essay traces the change in the values of the mother-in-law, linking it with social change as well as with the actors, once romantic heroines, who come to play this character in later years. While the importance of the song in Hindi films is a theme that recurs in many of the essays, the relationship of the star to the role, or the star-text, is equally significant. Part II, “The Business of the Body”, looks at courtesans, tawaifs, dancing girls, gangster’s molls and sex workers, delving into the slippages between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ femininity, and refers to cases in real life, to court rulings and laws as well as to star-texts and star lives. Part III, “The Question of Violence”, focuses on a different kind of badness, beginning with an essay on Bandini by Smita Banerjee, while Part IV, “The Advent of the New Woman”, has essays discussing Andaz and Shri 420 as well as Cocktail and Queen. “The Screening of the Actress” is the concluding part, presenting the figure of the actress in Hindi popular cinema — the culmination of the star-text — and contains an interview with Swara Bhaskar.

Of its three chronological tables, the one I most enjoyed was that of Angry Young Woman films.

‘Bad’ Women of Bombay Films: Studies in Desire and Anxiety edited by Saswati Sengupta, Shampa Roy and Sharmila Purkayastha, Palgrave Macmillan, 103.99 euros