Book: Asia after Europe : Imagining a Continent in the Long Twentieth Century

Author: Sugata Bose

Published by: Harvard

Price: Rs 699

Japan’s military victory over Russia in 1905 was a landmark moment flagging the cultural and economic “rise” of Asia. Over the ensuing half a century, driven by the growing triumvirate of Japan, India, and China, much hope was generated about Asia’s interconnected future. Sugata Bose’s book uses an epic canvas to bring into sharp focus a wide range of characters — both intellectual and subaltern — who played key roles in spawning and sustaining an interwoven tapestry of “intellectual, cultural, and political conversations.” These undergirded Asian versions of universalism and cosmopolitanism deviated from — and defied — European conceptions of nation-states, hard borders, unitary sovereignty, and imperialism.

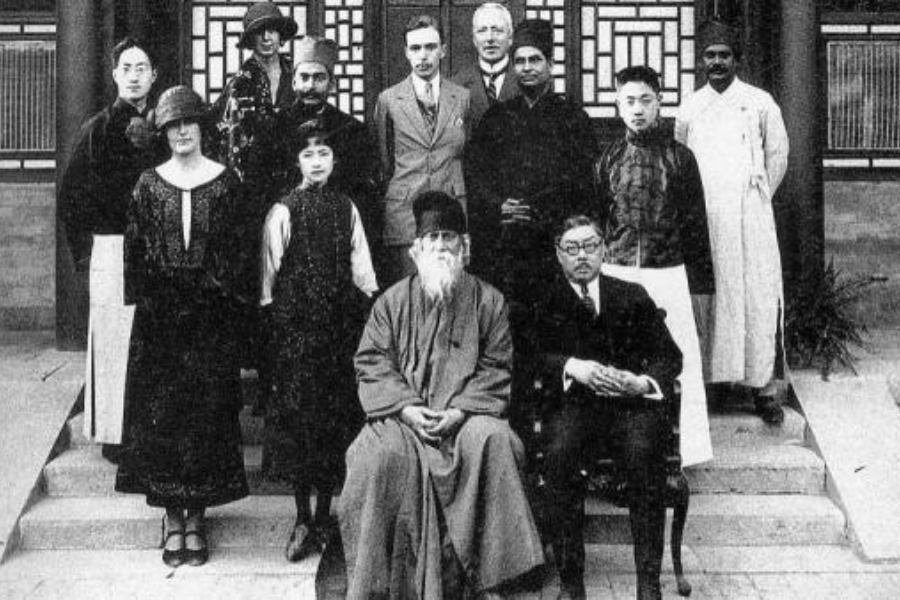

During the first half of the century, a range of remarkable individuals worked as conduits through which synergic streams of mutual learning, ideation, and creation flowed freely. They included, among many others, the Japanese art critic, Okakura Tenshin, who was in Bengal in 1902 and interacted extensively with the Tagore family; Yokoyama Taikan, the painter who followed in Okakura’s wake and not only painted Indian themes like Raas Leela but also helped effloresce the Bengal School of Art by teaching the Japanese ‘wash’ technique to Abanindranath Tagore; the scholar, Benoy Kumar Sarkar, who in the 1910s had engaging intellectual conversations in England and the US, but missed the affective bond that made him feel completely at home in Japan and China; Rabindranath Tagore himself who, during his visits to East Asia, struck up long-term and, sometimes, “argumentative” friendships with the Chinese scholar, Liang Qichao, and the Japanese poet, Yone Noguchi; the poet-philosopher, Muhammad Iqbal, who, at the 1931 World Islamic Conference in Jerusalem, proposed dropping the stigmatising prefix, “Pan” from “Islamism”; the leading Chinese artist, Xu Beihong, who visited Santiniketan in 1940 when he painted a portrait of Tagore and did a sketch of Gandhi (a decade later, the bold brushstrokes of his horses would inspire a young M.F. Husain to adopt a similar style for his own horses); or Debabrata Biswas, who sang Sukanta Bhattacharya’s “Bidroho aaj, bidroho charidike” (rebellion today, rebellion everywhere) before an appreciative Chinese audience, including Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai, during an Indian delegation’s visit to China in 1953.

In place of a dominant historical narrative identifying the twentieth century with movements of anticolonial nationalism, Bose lays open a new and seamlessly connected tapestry on which Asian and Islamic universalisms and Bolshevik/Communist internationalism lived out parallel but also interconnected and overlapping lives. This, however, changed in the late 1950s when the citizens and the political managers of Asia’s new nation states — frustratingly — failed to continue the transnational solidarities of anticolonial thought and chose to throw their lot with the European colonial-imperialist paradigm of nation states with hard borders and unitary notions of sovereignty. This incubated new conflicts and rivalries in old (European colonialist) bottles and destroyed the very roots of dialogue, exchange, ideation, and conversation that had raised the possibilities in the first half of the century of an Asian ascendancy based on sharing and solidarity.

Bose’s book revises several major pieces of wisdom in historical research. Defying the classic Anglophone idea of cosmopolitanism as something “pure” and detached — “untainted” by any flavour of patriotism — Bose’s characters are “colourful cosmopolitans”, with their patriotism providing the colour palette but never falling at odds with a cosmopolitanism that could easily transcend the lines of particular cultural differences. Bose also contradicts the position of the influential book, The Wilsonian Moment, by the historian, Erez Manela, by contending that the post-World War I overtures on national self-determination by the US president, Woodrow Wilson, had limited long-term traction in Asia. Here, instead, nationalists refashioned the idea of Asia in the early-1920s according to multiple competing but overlapping universalisms, most notably Islamic universalism but also closely followed by Bolshevik internationalism. Bose thus “re-Orients” perspectives on what are generally considered to be Euro-American drivers of global history.

Finally, Bose claims to offer a different method — compared to Dipesh Chakrabarty’s — of “provincializing Europe” by seeking to move beyond European definitions of reason, national identity, and federation. He does this by presenting a historical narrative that seeks to show “how a continental identity of, by, and for Asians was ... fashioned in myriad ways”, based on interactions spanning “a whole spectrum of intimacies, affective bonds, solidarities, and alliances” transcending the boundaries of nation, race, or religion. This is a powerful claim, taking the “transnational turn” in history-writing in a new direction by foregrounding intra-Asian exchanges and conversations.

In a fractious and embattled twenty-first century Asia, these legacies — as well as remnants — of alternative “world-making” through people-to-people contacts and intellectual-cultural cross-pollinations, Bose believes, still provide possibilities for a shared and (re)connected Asia of the future. As of today, this manifesto of a “determined reimagination of a pluralized [Asian] continentalism” may sound like the “audacity of hope”. But there can be little doubt that Bose has reprised a template that had served a “young Asia” well a century ago and, possibly, can do so again in the future.