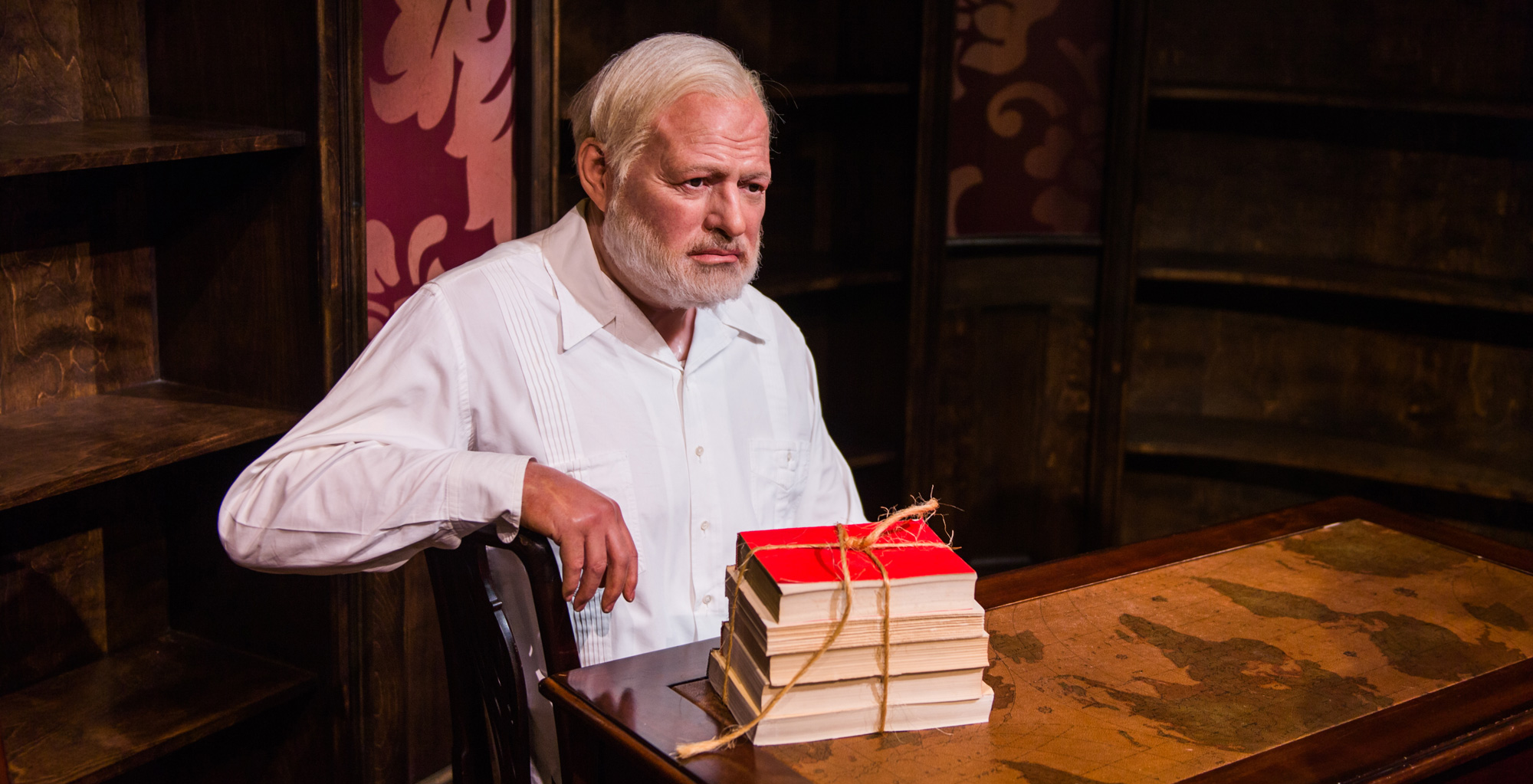

This relationship, which remained intense for much of two decades, had a deeper meaning. It mirrored the frustrating efforts to plant the seeds of peace on a philosophical and religious level which then should have percolated to the political and social levels. Rolland followed Tagore in widening these peace efforts by incorporating India’s spiritual way of life. Rolland felt inspired and comforted by it. Both were hoping that the ‘new man’ would evolve from the growing together of Europe and India. Indeed, Rolland felt that Europe “is on the decline” and “Asia must sooner or later reclaim its erstwhile primary position”. And he continues, “It is essential that it should be the Great Asia of divine and fraternal thoughts, and not of violence and vengeance, which the madness of Europe has done its best to provoke against itself.” In a single sentence the writer evaluates the context in which their struggle was set.

Tagore and Rolland are both prone to emphatic idealism which to us today appears somewhat vacuous. Has history made us by nature suspicious and caustic? Yet, from among the two correspondents, Rolland proves himself to be more realistic and sober. This becomes evident while reading about the episode which is the centrepiece of this book: the misunderstandings surrounding Tagore’s meetings with Benito Mussolini who was Italy’s brutal strongman when the Indian poet visited Italy in 1926. Tagore’s public utterances created the impression that he was in favour of the fascist regime. It swiftly exploited this to create a favourable image outside its borders. Readers who wish to get a full account of this unfortunate incident may refer to this book. Chinmoy Guha, the editor, adds corroborating letters and documents to create a more complex understanding of it. Although Rolland very respectfully admonished Tagore (but revealed how horrified he was in an openly critical letter to Kalidas Nag), this affair — in the words of Guha — “cast a long shadow on their relationship, if not a sense of guilt in Tagore, a hidden embarrassment”.

Although Tagore visited Rolland in Paris and in Villeneuve, his Swiss refuge, Rolland could never fulfil his craving to travel to Santiniketan. A leitmotif of this correspondence is also Rolland’s regret of not being able to communicate directly with the poet. His sister had to translate Tagore’s English. Another is the acknowledgment that Tagore’s troubled and Rolland’s reverential relationship with Mahatma Gandhi could not be harmonized.

The young historian, Kalidas Nag, a student of the poet, travelled to Europe in the 1920s. A fervent Francophile, he was in touch with Rolland and scores of other luminaries in France, Germany and Switzerland. Nag maintained a busy correspondence with Rolland (earlier published by the editor of the present volume), and both the Frenchman and the Indian repeatedly mention the interventions and letters of the enthusiastic scholar.

Guha has excelled himself in editing this book, giving exhaustive explanatory and interpretative endnotes, apart from an Introduction which is not only factual but also inspiring. He adds three recorded conversations between the two writers and several appendices in which he collects letters by people around Tagore to Rolland and from him, for example, Saumyendranath Tagore, who is an interesting, yet neglected, figure.

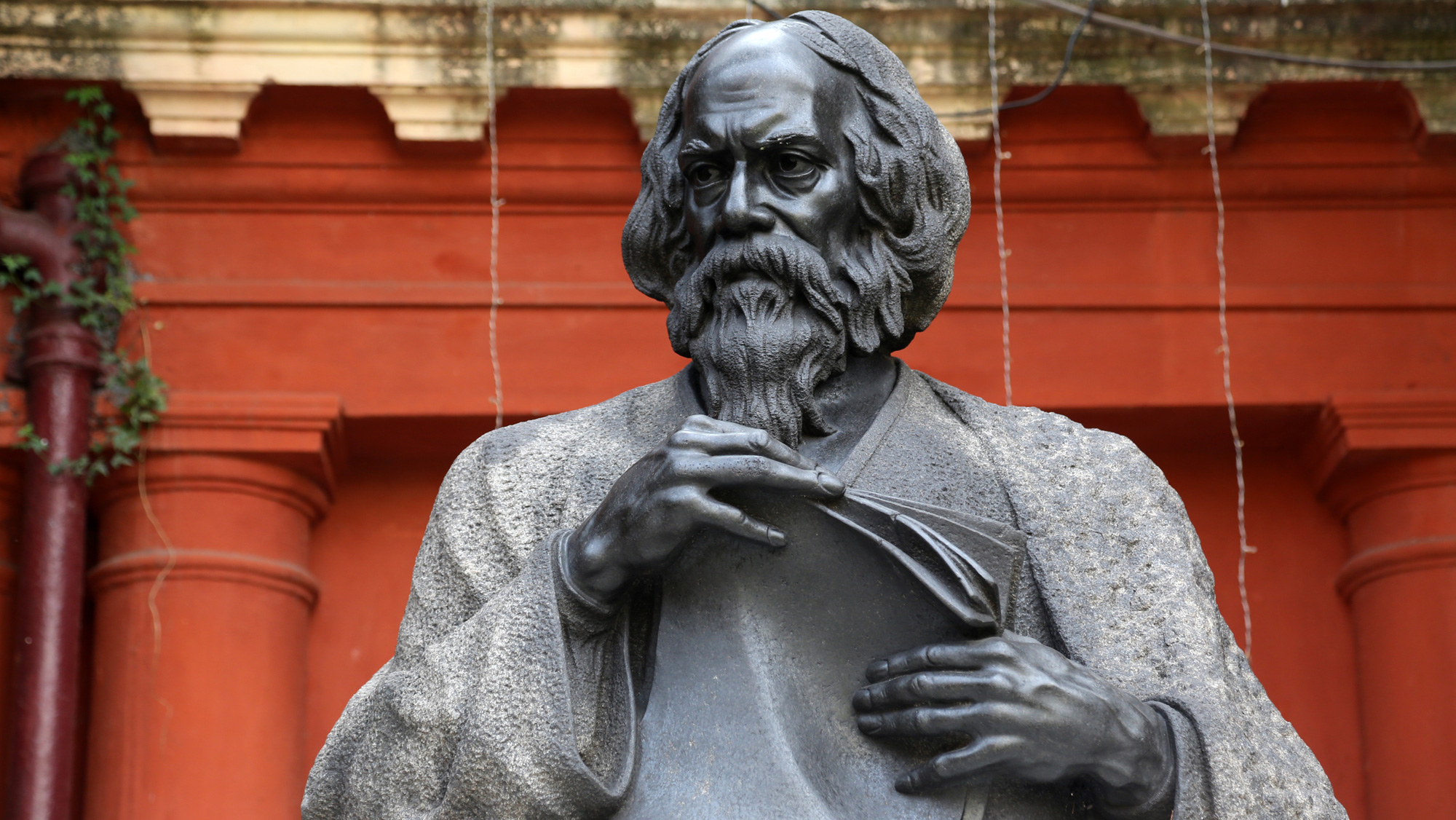

Bridging East and West: Rabindranath Tagore and Romain Rolland Correspondence (1919-1940) Edited and French letters translated by Chinmoy Guha, Oxford, Rs 995

The general concept is that Rabindranath Tagore’s principal interlocutor in continental Europe was Albert Einstein. To be sure, their status was equal, their relationship iconic, but their conversations, reprinted ad nauseam, offer little content. Reading the correspondence between the poet and the French writer, Romain Rolland, we witness two personalities who are deeply engaged in finding a lasting peace in the period between the two devastating World Wars.