In June 1744, the 19-year-old Clive arrived not in Calcutta but in the Company’s oldest settlement, Fort St. George in modern-day Chennai. Here he spent the next two years fidgeting as, seated at a high desk, he tried to take an interest in the Company’s ledgers or in negotiations with merchants. To relieve the boredom, he spent his spare time in the governor’s library, reading voraciously, rectifying at least in part the deficiencies in his education caused by his misspent youth.

Clive arrived in India at a time when many — Indian and European — were vying for power and influence amid the rivalries created by the slow disintegration of the once mighty Mughal dynasty. Aurangzeb, last of the six great Mughal emperors, had spent much of his life on campaign in the Deccan and southern India. A strict Muslim, his religious policies had divided the people of his empire, which after his death in 1707 had begun to decay — a fact brutally underlined when in 1739 Nadir Shah of Persia sacked Delhi and stole the fabulous Peacock Throne made for the Emperor Shah Jahan.

By Clive’s time, though the Mughal emperors still exercised some control in the north — Bengal, for example — through their vassals, in the south their suzerainty over rulers such as the nizams of Hyderabad was growing ever more theoretical. The resulting power vacuum encouraged local rulers to challenge for power and provided chances for European countries — especially Britain and France — to profit from Indian disunity.

Clive is remembered for his unbridled and unbounded exploitation of such opportunities, both on his own and the Company’s behalf, and for his military ingenuity. However, as a lowly Company employee, he had to await his moment. His opportunity came with the outbreak of the First Carnatic War — in part an extension into the Indian subcontinent of the European War of the Austrian Succession — in which Britain and France supported rival Indian factions. In September 1746, French troops captured Madras and Clive was taken prisoner. However, he escaped south to Fort St. David, the English East India Company post at Cuddalore, where he enlisted in the Company army and played a notable role in the fort’s defence.

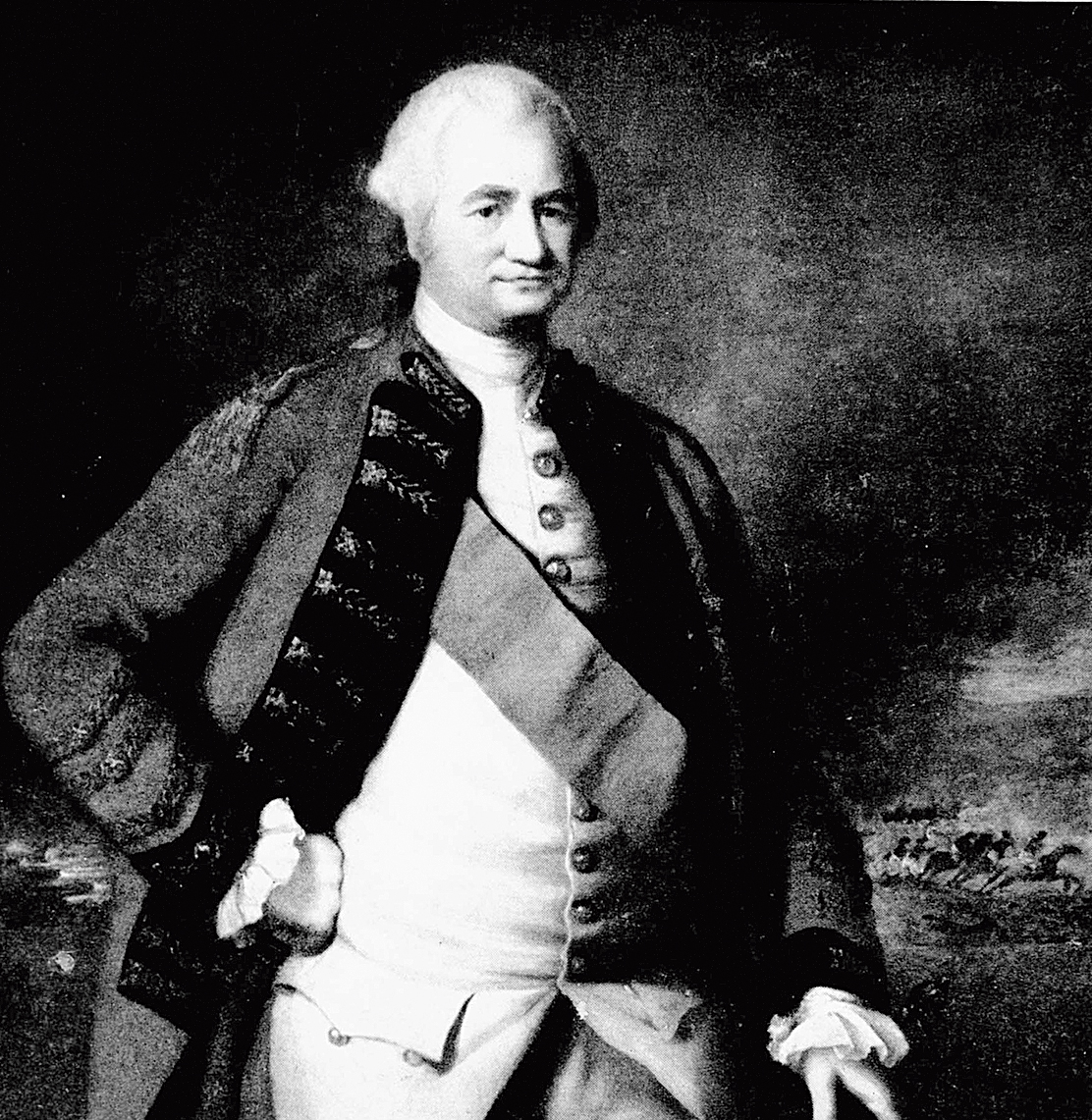

Thus began a swift rise for this once troubled and troublesome young man whose overriding ambition meant quarrels with his fellows were inevitable. In 1751, Clive’s seizure and defence of Arcot against the numerically superior forces of Chanda Sahib caused British Prime Minister William Pitt the Elder to hail him as “the heaven-born general”. Soon after, Clive married and returned to England. However, by 1755 he was back in India as deputy governor of Fort St. David. Soon, however, his attentions turned to the Company’s activities in fertile Bengal.

In 1756, the 23-year-old Mirza Muhammad Siraj-ud-Daulah succeeded his grandfather as Nawab of Bengal. Far less tolerant of the Company’s ambitions than his forebear, he attacked Calcutta and seized it when Governor Drake and British officials fled ignominiously down-river to Falta. A number of Europeans were crammed into the “Black Hole” — a small, airless chamber in the Company’s erstwhile headquarters of Fort William — where some perished. Both the number of those imprisoned and those who died are much disputed but are commonly agreed to be many fewer than the British then and later during the Raj alleged.

Reeling under losses both physical and financial and fearing the loss of their other settlements to the French, who were supporting Siraj-ud-Daulah, the Company was determined to retake the city and, despite their reservations about his quarrelsome character and conduct, despatched Robert Clive to expel the Nawab’s forces. By a mixture of planning, leadership of his ordinary troops and sheer determination, on January 2, 1757, Clive duly retook Calcutta. He followed up this success some weeks later when, with some of his troops carried up the Hooghly river by the naval vessels of Admiral Watson and some advancing along the riverbanks commanded by himself, he captured the French East India Company settlement of Chandernagore, effectively blunting French ambitions in Bengal.

The battle with which Clive’s name would inextricably be linked followed three months later when on June 23, 1757, with 2,000 Company Indian soldiers and 800 European infantry and artillerymen, he overcame Siraj-ud-Daulah’s army of 50,000 at Plassey near the mango groves of Lakash Bagh. The key to his victory was the treacherous defections of three of the Nawab’s commanders, Mir Jafar, Lutuf Khan and Rai Durlabh, all heavily bribed in a series of duplicitous negotiations which reflected no credit on anyone involved.

For Clive personally, victory brought all the power, glory and money he had craved. Mir Jafar, to whom Clive had promised the throne of Bengal if he turned against Siraj-ud-Daulah, rewarded him lavishly on becoming Nawab. After Clive led the defence of Mir Jafar’s lands against an invasion by the son of the Mughal emperor, Mir Jafar rewarded him with further, by no means unsolicited, large presents including a personal land grant.

The grateful Company appointed Clive Governor of the East India Company Presidency in Bengal and from this period he began to advocate that the Company should take control of territory as well as trade in the region. At the same time, he quarrelled with many Company officials and army officers and continued to acquire powerful enemies such as the equally irascible and successful British Army officer, Major Eyre Coote.

Returning to Britain in 1760, Clive was forced to defend his land grant from Mir Jafar against charges that it was against the Company’s interest, not least because the land should have gone to the Company rather than to him personally. However, Clive blunted these claims and, though frequently debilitated by obscure nervous ailments and pains, became a member of Parliament. Subsequently, he persuaded the Company and Parliament to return him to Bengal to purge the administration there of corruption caused by the “present taking” of officials — somewhat ironic in view of his own behaviour.

Back in Calcutta, Clive’s actions led to increasing de facto Company control of Bengal and its revenues. Despite his supposed anti-corruption remit, he was accused of what would now be “insider stock trading”.

Clive finally returned to Britain in 1767 with a personal fortune then estimated at 4,00,000 pounds sterling, a vast sum. However, controversy over his character and role in the Company’s activities soon led to a parliamentary inquiry. Clive spent much of his remaining life defending himself against charges including that during his most recent time in India he had allowed corrupt officials to abuse monopoly rights and, even worse, that the high land taxes he had levied had precipitated the great famine in Bengal of 1769-1773. Also accused of enriching himself through corruption, Clive replied, “I stand astonished at my own moderation.”

The mercurial, talented but fundamentally flawed Clive died in London in November 1774, aged only 49, after stabbing himself with a pen-knife. His death was perhaps a result of depression. Like that other controversial character Winston Churchill, Clive was often subject to those dark moods which Churchill likened to having a black dog on his back. Possibly Clive acted under the influence of opium of which he had become an ardent user while in India to enable him both to sleep and dull his alternating moods of depression and hyperactive ambition.

Trying to understand the complexities of this larger than life character and why, despite his obvious flaws, he became such a famous figure has been my task in writing Fortune’s Soldier. To some, the 19th century historian Lord Acton’s words seem an appropriate epitaph: “power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely”. Or perhaps as the other leading but fictitious character in Fortune’s Soldier suggests, how much better it would have been for Clive if, during his victory parade after Plassey, there had been someone to whisper in his ear, as a slave did in the ear of Roman emperors during their triumphal entry into Rome, “Remember you are mortal.”

Alex Rutherford is the author of Fortune’s Soldier, a fictional biography of Robert Clive recently published by Hachette

Even in his lifetime Robert Clive attracted great controversy, and over the nearly two-and-a-half centuries since his death in London in mysterious circumstances, he has attracted much more. While still a schoolboy, growing up in the midlands and northwest of England, his uncle complained that he was “out of measure addicted to fighting”. Wherever he went to school, he made trouble and later joined a gang of youths who forced local merchants to pay them protection money or risk having their premises ransacked. Perhaps in desperation, his father Richard Clive, a landowner and lawyer, despatched his unruly young son to India to become a “writer” — a junior clerk — in the East India Company. It was an unlikely calling for such a pugnacious young man.

Founded in 1600, by Clive’s time the Company had become Britain’s largest and most important trading company. A court of 24 directors managed its activities from East India House in the city of London, accruing great wealth for themselves and their investors. The main hubs for the activities in India were the presidencies of Calcutta (Kolkata), Madras (Chennai) and Bombay (Mumbai).