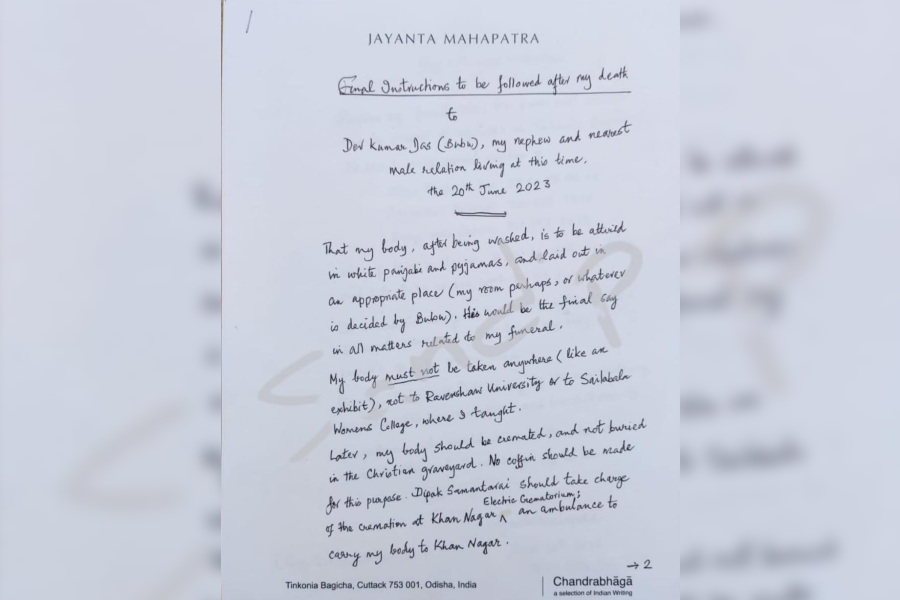

The globally acclaimed poet from Odisha, Jayanta Mahapatra, believed in the mystery of human existence right through his life. And it seems the vision of leaving the world came to tease him to rethink the ever-persistent question of mortality. Sixty-odd days before he died, on June 20, the 95-year-old poet delivered a hand-written note about how his body was to be prepared.

“Final instructions to be followed after my death” (issued to his nephew Dev Kumar Das, Bubu): “That my body, after being washed is to be attired in Panjabi and pyjamas, and laid out in an appropriate place (my room perhaps or whatever is decided by Bubu). … My body must not be taken anywhere (like an exhibit), not to Ravenshaw University or to Sailabala Women’s College, where I taught. Later, my body should be cremated, and not buried in the Christian graveyard. No coffin should be made for this purpose....”

Poet Jayanta Mahapatra’s written final instructions to be followed after his death. Paramita Mukherjee Mallick

During the terrible famine of 1866 in Odisha, his grandfather, Chintamani Mahapatra, who came from an illustrious family, ran away from home to be able to get food and survive. Jayanta Mahapatra’s poem Grandfather came towards the last quarter of his life. The 1866 famine is regarded as one of the world’s worst famines and it killed a million people of hunger. The disaster was a result of drought, severe lack of planning of rice rations for the people, and a horrific mismanagement of food supplies by the British administration of India. There was a desperate attempt by grandson Jayanta to relieve the hunger in his grandfather Chintamani’s stomach for a handful of rice, in his poem:

Did you hear the young tamarind leaves rustle

in the cold mean nights of your belly? Did you see

your own death? Watch it tear at your cries,

break them into fits of unnatural laughter?

How old were you? Hunted, you turned coward and ran,

the real animal in you plunging through your bone.

You left your family behind, the buried things,

the precious clod that praised the quality of a god.

In the poem Grandfather he asks again and again, “What does religion or faith matter in the end if the body is not able to get the necessities like food in the stomach.” For this poet, the element of mystery lies deep in his consciousness and is articulated occasionally: “Mystery is like the rain, falling like false jewels in the sky, which catch the light as they fall, like the trail of a rainbow; and perhaps it is these bits of a rainbow which a poem should catch to be able to move the reader and instill in his or her mind a ‘stirring’ of some kind.”

What Mahapatra lost on the swing, he made up on the roundabout. He may have entered the arena of writing poetry rather late in his life, but he more than compensated the lateness with his robust and evocative use of images, and constantly constructing and deconstructing ideas that he created and then broke down in the course of his poetry.

Mahapatra is remembered for having sown the first seeds of Indian English poetry, along with A.K. Ramanujan and R. Parthasarathy, seeds that found fertile soil. Unlike the Bombay poets such as Dom Moraes, Arvind Krishna Mehrotra and Parthasarathy, who wrote about their urban lives, Mahapatra’s poetry was focused on the small town and the rural scape.

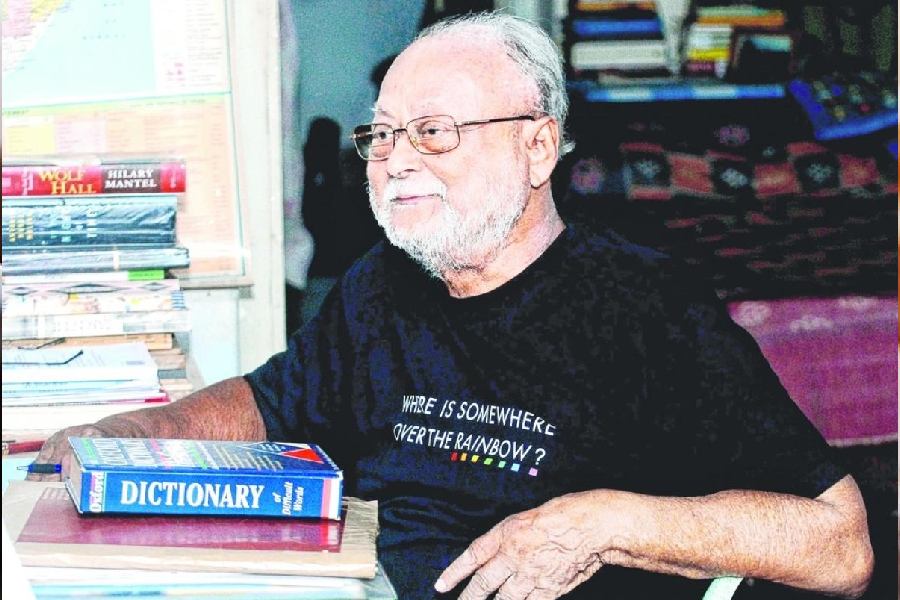

Poet Jayanta Mahapatra with educationist and author Paramita Mukherjee Mullick. Paramita Mukherjee Mullick

There is a resonance in the poetry of this Postcolonialist with double Booker Prize awardee Sri Lankan-Canadian poet Michael Ondaatje in Rat Jelly and Other Poems and Handwriting: Poems. Like Ondaatje’s poetry, silence exerts an air of mystery that makes Mahapatra reach into the unknown to sense things he had never felt before.

As a meticulous translator of many texts from one language into another, he says: “So, for me, a poem is knit together by an inconceivable silence. Silence which is an intangible substance, of which words are but manifestations, words which can build the poem from a silence and to which the poem must eventually return. Does this silence lie within the heart? Maybe it does, as it waits to burst out of one with a childlike pang of pain on its way to becoming the idiom of the poem. For this silence is a sound I will always remember, as it appears to move through my days, and I feel it like an armour I sheathe myself in, to protect myself from the outside world.”

Thus, his poem Hunger, which delivers a sledgehammer as it examines the hunger for pleasure — sexual satisfaction — pitted against the hunger for food due to starvation that stems from the need to eat just to survive. The feeling of sadness and a sickness of the soul are contiguous in the first reading of the lines by a starving father to a man who is at first overwhelmed with the hunger of sensual pleasure of devouring the flesh of his famished 15-year-old daughter who has been reduced to bone covered in skin:

I heard him say: My daughter, she’s just turned fifteen…

Feel her. I’ll be back soon, your bus leaves at nine.

The sky fell on me, and a father’s exhausted wile.

Long and lean, her years were cold as rubber.

She opened her wormy legs wide. I felt the hunger there,

the other one, the fish slithering, turning inside.

In his poem Freedom, the idea of liberation in the Indian context is muddled and parochial. The rural economy of the past is the receptacle of poverty and hunger while the spanking new economy is full of self-serving pillars of concrete with no compassion in the walls of the state. The hungry mother and child become another leitmotif of ‘unfreedom’ and slavery.

Not to meet the woman and her child

in that remote village in the hills

who never had even a little rice

for their one daily meal these fifty years.

And not to see the uncaught, bloodied light

of sunsets cling to the tall white columns

of Parliament House.

In the new temple man has built nearby,

the priest is the one who knows freedom,

while God hides in the dark like an alien.

If some readers find his poems difficult to grasp at first reading, Mahapatra explains: “This is what some critics have said about my poetry: that it becomes obscure, not giving up its meaning easily to the reader after one reading. But I ask myself: What use is a poem if it is easily understood?”

He once said: “And yet, our sense of what a poem is, is formed out of the very fact of assimilation of those many poems we have encountered through the years, and it is no use denying that these links have not been made in one’s poetry. I should like to think that this has happened in the poetry I have written. If the quality of mystery appeals to me, then this has come from the value I have learnt to place on how such words and ideas have gone on to become poetry. And this poetry, like all other art perhaps, alternated between deception and revelation.”

In 1995, in a series of talks, Mahapatra invoked the Romantic poet P.B. Shelley, who believed in the philosophy that poets were the unacknowledged legislators of the world. In the years post-1995 he clearly said: “Poetry has always been responsible to life. By this, I mean that a poet is first of all responsible to his own heart, otherwise he cannot be called a poet. And maybe those other factors which are necessary to the makings of a good poet will come only later. And so, if the poet’s conscience matters, it seems but natural that he would write about those things which appear unfair to him.

“It is the poet again who will talk about injustice and cruelty and greed in the society in which he lives, hoping in his heart of hearts that these would be taken care of. Certainly, one cannot place the poet in the role of a social reformer; but there can be no denying the fact that he would like to see a just and fair society come into existence, to see the smile appear on the face of every destitute child on the street, on every man, woman, and animal on this earth he inhabits.”

In Freedom, Mahapatra presents with gripping lucidity the binaries between rich and poor, slums and mansions, the powerful and the disempowered. Sights to which we have become jaded are exactly the everyday wake-up calls to this poet’s conscience. “Silence exerts an air of mystery that makes me reach into the unknown, to sense things I had never felt before,” he has said repeatedly.

Julie Banerjee Mehta is an author of Dance of Life and co-author of the bestselling biography Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. She has a PhD in English and South Asian Studies from the University of Toronto, where she taught World Literature and Postcolonial Literature for many years. She currently lives in Calcutta and teaches Masters English at Loreto College