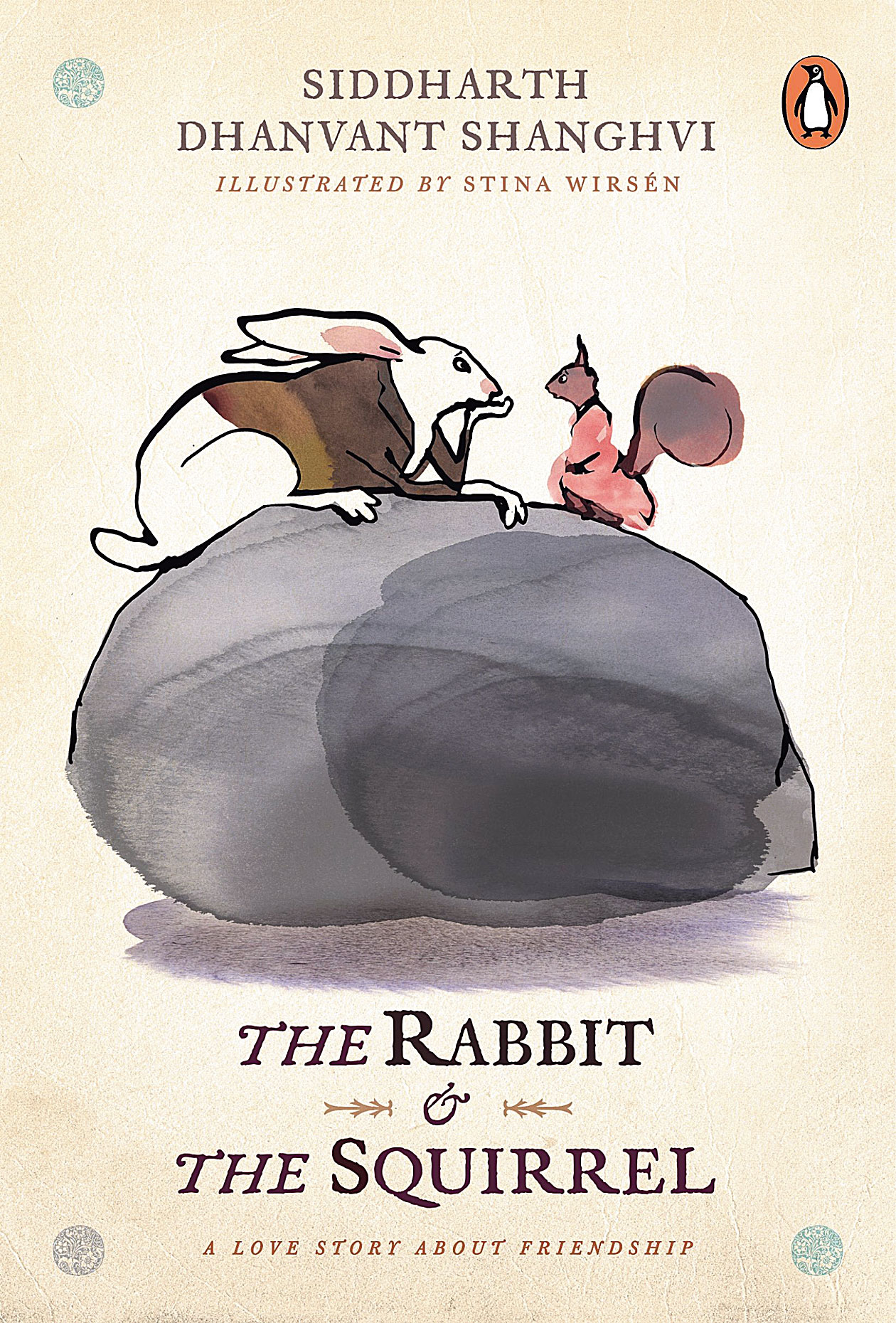

His Rabbit and Squirrel are making quite a noise in the literary circles. Illustrated by Swedish artist Stina Wirsen, Siddharth Dhanvant Shanghvi’s fable for adults, The Rabbit & The Squirrel, is a lesson on love and friendship, for those lost in the wilderness of life.

It is the story of two friends, the Rabbit and the Squirrel who existed in their own little world where “atop the little black rock that felt like the end of the earth, they knew no fear, they experienced no anxiety and they were safe — even from the gods”. The 64 pages track how the friends meet and part and meet again under different circumstances, taking the readers on a lilting journey of companionship.

In a world that’s learning the importance of ‘self-love’ and ‘finding oneself’ at a fast pace, this book is a reminder to pause, take a step back, look at the bigger picture and then start moving forward again, at one’s own pace. Wirsen’s watercolours are a bonus. Here’s what Shanghvi, who authored The Last Song of Dusk in 2004 and The Lost Flamingoes of Bombay in 2009, told t2 about his new book in an email chat.

How did The Rabbit & The Squirrel happen?

It was a gift for a friend who was leaving the country — I had to give her something to remember our shared, secret hours. The tragedy at the heart of The Rabbit & The Squirrel is not their separation as much as their inability to recognise that what they shared was perfect already. The poet Nick Laird wrote ‘Time is how you spend your love’ which led me to consider the converse: without love, what is the meaning of time?

The illustrations take the book to another level...

Stina Wirsen is Sweden’s most celebrated illustrator and children’s book writer. You will agree that her beautiful, compelling, singular work brings this little story to life — she offered to illustrate the book, she is my close friend and co-creator of this little fable.

Witty puns aside, why animals?

Because they are infinitely more charming than people.

“If you are waiting, it is because you are deserving; If you are deserving, it is because you have waited.”

In Bengali there is a phrase called dukkho bilaash which roughly translates to someone beginning to enjoy melancholia. Do you believe this as opposed to someone actively trying to move on?

I believe you move on when you move on. These things cannot be hurried. ‘Heartbreak has its own way of inhabiting time,’ writes David Whyte, ‘and its own beautiful and trying patience in coming and going.’ In a sense everything can become a medium to build self-love, but equally grief, and then the tentative hours when we believe recovery is imminent.

The Rabbit wanted to tell the Squirrel all about his life that had passed by and yet he doesn’t actively seek her out. Why not?

I believe his education is solitude, and from that comes the knowledge that people are returned to us when it is exactly the right hour. This happens with the book’s two characters, and even if their reunion is brief, perhaps even tragic, it is also as whole as a lifetime. Remember that line by Blake — Hold infinity in the palm of your hand/And eternity in an hour — if you are lucky you get such an hour, and if you are wise, you recognise it.

There is a quaint juxtaposition of love and the comfort of being alone. Where does one find middle ground between the two?

That’s an entirely individual formulation. However, I am drawn to the wisdom of Rilke, who advised lovers to strengthen each other’s solitude, to stand guard over their aloneness. A good friend is someone who bears witness to your life so you can, one day, believe your life — yes, it happened, you were grief-struck, you had been ecstatic. In the end, the Squirrel wants to go dancing with the Rabbit — she must remind herself of the hours she has been most alive.

The Rabbit & The Squirrel; Penguin Random House Rs 399 (Book Cover)

Do you believe in karma?

Yes.

“They wept because everything was unbearably beautiful, and their time to experience any of it was dreadfully short”

One is reminded of Juan Eliya. Who are your inspirations?

Many artists. I am drawn to the fine, minimalist work of Sol LeWitt; the poems of Billy Collins; the architecture practice of Geoffrey Bawa and Tadao Ando. I am drawn more to architects and their work — I see the value of drawing up clear plans before proceeding.

The life you live in Goa sounds awfully similar to the one the Rabbit chose for himself. Are you waiting for your Squirrel? How much of you is present in the book?

I am here to inhabit time more fully, and to allow for experience to move through me. The book is emergent from a discipline of waiting without expectation, and of pleasure in absence, and pleasure with presence.

Photography, design and writing — what is closest to you?

All practices lead into each other. Photography taught me to bring a scene to life. Design has showed me how things are deeply connected, and how these connections exist meaningfully in unison and not by exclusion. Writing is a way of refining the process of thinking; it is a kind of whittling down until very little remains.

What is your writing process like?

It has been undisciplined for the last decade. I am now determined to rectify this: I am now trying to rise as early as four to write more, and clearly.

What can we expect next from you? More importantly, when?

I wish I knew!