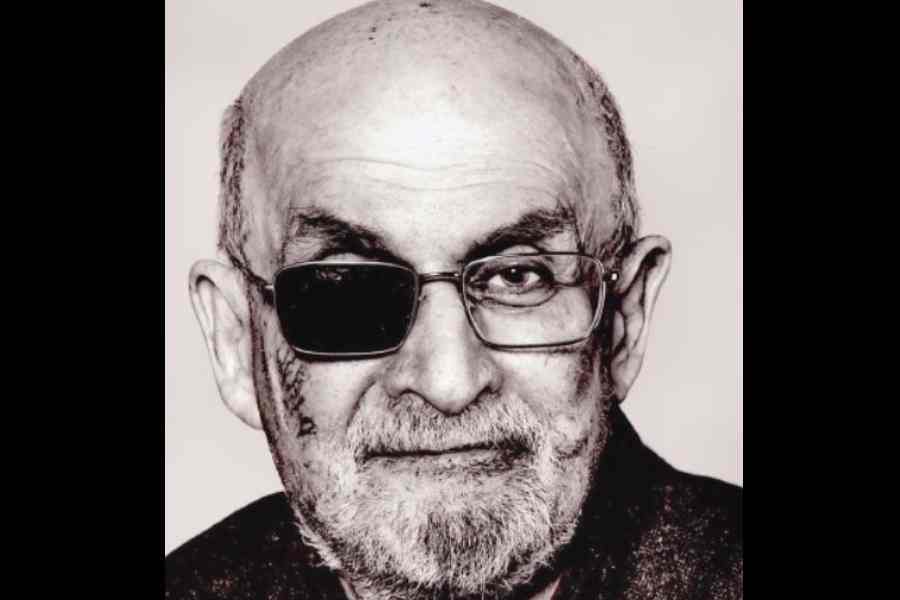

VICTORY CITY By Salman Rushdie, Hamish Hamilton, ₹699

Back in 2001, Edward Said had noted that the acrimonious debate surrounding Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses was never really about its literary attributes but about the literary treatment of a topic that exacerbated religious passions. Said’s observations remained valid as Rushdie suffered a near fatal attack at the hands of a young bigot in August 2022. Given Rushdie’s narrow escape, his triumphant return with Victory City has rightly renewed the debate over censorship and literary freedom.

The fable in Victory City is evident from the start, from the time we are introduced to the “blind poet, miracle worker and prophetess”, Pampa Kampana, and are told about her implausible age, her “immense narrative poem about Bisnaga” and its improbable discovery four and half centuries later. Nonetheless, an attentive reader will recognise that more than ingenuity, Rushdie imaginatively exploits the richly textured medley of genres that constitute the historiography of Bisnaga/ Vijayanagara empire. Be it the 16th-century Portuguese travel accounts of Domingo Paes and Fernao Nunes or the indigenous folk and literary accounts, Rushdie’s fabulous story is intertwined with textual histories.

For instance, one finds echoes of a 13th-century tragic event — a largescale killing of people, including women, ordered by the King of Bisnaga before his surrender to the King of Delhi — in the carnage that Pampa Kampana witnesses as a nine year old. Likewise, the founding myth of Bisnaga city, in which the King is said to have witnessed a lone rabbit attacking a pack of dogs, surfaces in Pampa Kampana’s travels before she arrives at Vidyasagar’s mutt. Even the infamous blinding episode, which bears an uncanny parallel to the attack on Rushdie, can be found in textual accounts concerning King Krishnadevaraya.

However, since the focus is on Pampa Kampana’s tale, the fable threads through history and unspools itself sporadically. Named after a mighty river and a goddess, Pampa Kampana asserts her half-mythic name and status before the Sangama brothers and distances herself from the name that Vidyasagar had given her — Gangadevi, a name that recalls the 14th-century courtesan who wrote a poetic tale about the exploits of her royal lover, prince Kumara Kampana. Later in the novel, the narrator, the “spinner of yarns”, offers an ingenious gloss on the possibility of Pampa Kampana being the same as Gangadevi and concludes by saying, “We cannot know the truth. We can only surmise.”

Throwing a convenient veil over historical personages and events, Pampa Kampana’s fable grows wings and takes off. Armed with the gift of youth and magic, she generates creativity, freedom and equality, and becomes the queen to two successive kings. The twist in the tale is not difficult to see as her female power clashes with the male power of religion, violence, and Statecraft. Her magic seeds of time sprout and wither in accordance with dynastic desires and follies. The fate of the people mirrors this rise and fall.

When things get tough, Pampa Kampana exiles herself with her daughters to remote forests. She waits to stage a spectacular return, to recreate her glory by ‘ruling’ over ascetics and ministers. However, the death of her only great-great-granddaughter ends her dreams of a fabulous female dynasty and she hurtles to her doom at the hands of the raging king. Relegated to a cell, she sightlessly observes the madness which engulfs the future course of Bisnaga. Everything is destroyed, only her immortal jayaparajaya, the book of victory and defeat, survives.

Victory City is not an evenly told tale. The forest section is replete with tiresome allegories of pink monkeys and contrived accounts of female friendship. The blinding episode in the third section suffers from a lack of logic, especially the King’s sudden keenness for his poisonous wife’s sermons. And the third-person narrator is unnecessarily intrusive. But beyond the inevitable gaps and silences, the question of intention remains. In the essay cited at the beginning, Said had pertinently observed that the real debate underlying The Satanic Verses was one of literary freedom, or “literature’s apartness”, as he chose to phrase it. Besides pleasure, what is the political purchase of this ‘apartness’ in Victory City, and how effectively does it shore up Rushdie’s claim in the public domain?

Cleverly told, Victory City shows that ‘apartness’ can never be apart from history. More important, since history must be told, not invented, Rushdie’s fable is a great vehicle for telling the ‘story’ of Vijayanagara which has been extolled by nationalists as the epitome of Hindu civilisation. Cocking a snook at the bigoted binaries of our muscular nationalism, Bisnaga presents a credible mosaic of nationalities and religions and of political alliances and strategies. At the same time, its cautionary tale illustrates how the heady mix of State power and religion can punish or exile dissenting creativity. Victory City lives up to its name. Let’s hope the bigots are vanquished.