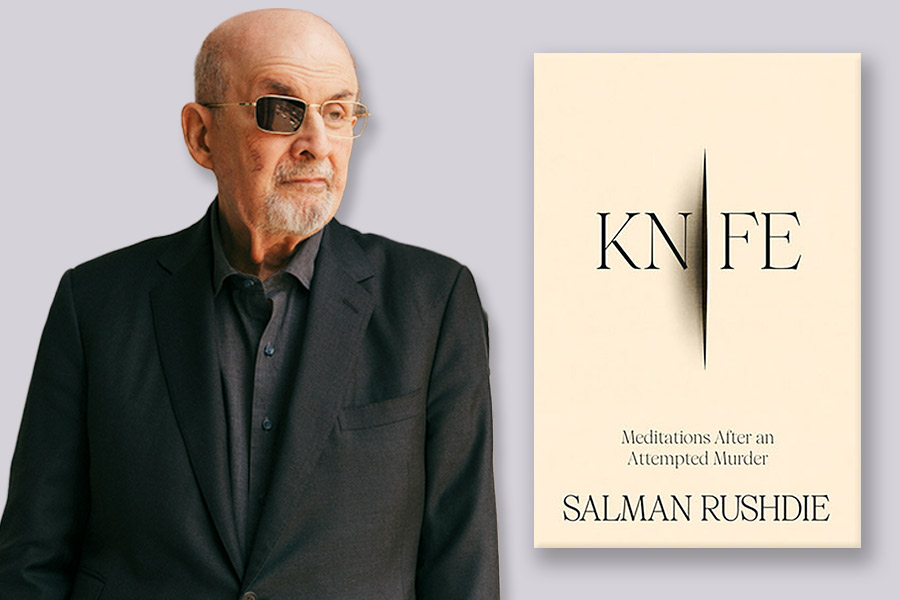

‘Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder’

By Salman Rushdie

Random House. 209 pages. Rs 699

“So it’s you,” Salman Rushdie remembers thinking on the morning of Aug. 12, 2022, as a black-clad man, a “squat missile,” sprinted toward him on an auditorium stage in Chautauqua, New York. Rushdie thought: “Here you are.”

Thirty-three years had passed since the former supreme leader of Iran, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, issued a fatwa ordering the deaths of Rushdie and everyone involved in the publication of his 1988 novel, “The Satanic Verses.” It had been at least two decades since Rushdie stopped running. He had been living an almost normal life in New York City. Socially, he had become a giraffe, eating leaves from the tops of the highest trees, but he was seen in dive bars too.

The black-clad man was an apparition from an older, more punitive world, one Rushdie thought had largely forgotten about him.

It is among that August morning’s ironies that Rushdie was in Chautauqua to participate in a discussion about keeping the world’s writers safe from harm. His attacker had piranhic energy. He also had a knife. Too stunned to try to protect himself, Rushdie only raised his left hand. At first, some in the audience thought the scuffle was performance art.

Cover of the book 'Knife' NYT

In his candid, plain-spoken and gripping new memoir, “Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder,” Rushdie describes what happened next. The black-clad man, stabbing wildly, had 27 seconds alone with him. That is long enough, Rushdie points out, to read one of Shakespeare’s sonnets, including his favorite, No. 130. He does not print the poem, but I will, to provide a sense of the interminable horror. This is 27 seconds:

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun;

Coral is far more red than her lips’ red;

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks;

And in some perfumes is there more delight

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

That music hath a far more pleasing sound;

I grant I never saw a goddess go;

My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground.

And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare

As any she belied with false compare.

His attacker was at last subdued. Blood was everywhere, pooling. Rushdie’s clothes were cut off him. His legs were raised to keep what blood he had left flowing to his heart. He remembers feeling humiliated. “In the presence of serious injuries, your body’s privacy ceases to exist,” he writes. The reader considers it a good sign, for Rushdie’s health and for the tone of this humane and often witty book, that among his first thoughts was, “Oh, my nice Ralph Lauren suit.”

A member of his surgery team later tells him, “When they brought you in from the helicopter, we didn’t think we could save you.” Rushdie describes the appalling damage:

“There was the deep knife wound in my left hand, which severed all the tendons and most of the nerves. There were at least two more deep stab wounds in my neck — one slash right across it and more on the right side — and another farther up my face, also on the right. If I look at my chest now, I see a line of wounds down the center, two more slashes on the lower right side, and a cut on my upper right thigh. And there’s a wound on the left side of my mouth, and there was one along my hairline too.

"And there was the knife in the eye. That was the cruelest blow, and it was a deep wound. The blade went in all the way to the optic nerve, which meant there would be no possibility of saving the vision. It was gone. ”

As bad as this was, he had been fortunate. A doctor says, “You’re lucky that the man who attacked you had no idea how to kill a man with a knife.”

This is Rushdie’s second memoir. His first, “Joseph Anton” — the title refers to the pseudonym he used when in hiding — was published in 2012. “Joseph Anton” is a sophisticated and multilayered book that recounts his years on the lam. It’s a book about friendship, about the many people who took him in. It was also a book about divorce. He was in the process of separating from his second wife, novelist Marianne Wiggins, when the fatwa was announced, and during the book his third marriage, to Elizabeth West, falls apart as well.

“Knife,” on the other hand, contains a love story. Rushdie recounts meeting, wooing and marrying American poet and novelist Rachel Eliza Griffiths, three decades his junior. She is now Lady Rushdie; her husband was knighted in 2007 for services to literature. Their story adds buoyancy to this memoir. But it takes a long time for that light to pour in. First there will be arduous recovery and rehab.

Poet John Berryman said an artist is lucky when “presented with the worst possible ordeal which will not actually kill him. At that point, he’s in business.” This is cynical but true. I’ve rarely read about worse physical trauma.

Rushdie is initially held together by staples. His ruined eye bulged out of its socket and hung down his face “like a large soft-boiled egg.” He spends time on ventilators. There were small bags attached to his body to gather a variety of leaking fluids. No one will permit him to look in a mirror. Mentally, he tortures himself. Why had he not defended himself? Was it that he was 75 and his attacker 24?

“On some days I’m embarrassed, even ashamed, by my failure to try to fight back,” he writes. “On other days I tell myself not to be stupid, what do I imagine I could have done? This is as close to understanding my inaction as I’ve been able to get: The targets of violence experience a crisis in their understanding of the real.”

This is not, it must be said, the most elegant book. It does not have the emotional, intellectual and philosophical richness of journalist Philippe Lançon’s memoir “Disturbance” (2019), about surviving the 2015 Charlie Hebdo magazine attacks by thugs claiming allegiance to al-Qaida. But Rushdie was wise to largely stick to the details and stay out of his story’s way. To paraphrase Roy Blount Jr., I put this book down only once or twice, to wipe off the sweat.

During Rushdie’s convalescence, his friend Martin Amis died. Another friend, editor and food writer Bill Buford, nearly expired from heart problems. Another, Paul Auster, discovered he had cancer. “There have been many times since the attack,” Rushdie writes, “when I have thought that Death was hovering over the wrong people.”

His mind, a free-associating unit, is intact. The literary and film references in “Knife” run deep. Along the way we learn that Rushdie is a “Law & Order” fan, that against his better judgment he orders books from Amazon, and that he needed the Chautauqua check to pay for a new air conditioning system. And so on.

Humor bubbles up organically from pain. “Dear reader, if you have never had a catheter inserted into your genital organ, do your very best to keep that record intact,” he writes. He enjoys that one of his surgeons has “the improbably gastronomic name of James Beard.” His account of a prostate exam includes these lines: “Aaagh. Double aaagh. Even more aaagh.” He is self-deprecating about his weight, which was 240 at the time of the attack. He lost 55 pounds in the months that followed. He does not recommend his weight loss technique.

He no longer has any urge, he writes, to defend “The Satanic Verses” or himself, although renunciation is the last thing on his mind. “If anyone’s looking for remorse,” he writes early on, “you can stop reading right here.”

Near the end of this memoir there is a sharp pivot. Throughout, Rushdie has provided pellets of information about his hostile and ill-informed attacker, whom he chooses to refer to as “the A.,” instead of the less decorous label (the Ass) he would prefer to use. Before the attack, the A. had been in Chautauqua for several nights, sleeping rough, checking out the site. He carried a false ID, his fake name an amalgam of the names of well-known Shia Muslim extremists. He had been living in his mother’s basement in New Jersey, playing video games and watching Netflix. He’d been radicalized by YouTube videos and, his mother suspected, by a trip to Lebanon in 2018.

Rushdie decides against trying to speak to him face to face. Instead, he imagines an interview with him, a conversation that consumes 30 pages of this book. I will not give the contents of this imagined interview away, except to say that the topics include radicalization, the ruthlessness that comes with the blinkered conviction that your cause is just, translation, hatred, laughter, literacy, gym memberships, mothers and the New York Giants.

Rushdie is no Oriana Fallaci, and no Tom Stoppard. I am not sure this section entirely comes off, but I am still processing it. Their fictional exchange did put me in mind of a bitter line from Lançon’s book, uttered by satirical cartoonist Stéphane Jean-Abel Michel Charbonnier, better known as Charb: “If we start respecting people who don’t respect us, we might as well close up shop.”

“Knife” is a clarifying book. It reminds us of the threats the free world faces. It reminds us of the things worth fighting for. Rushdie’s friend Christopher Hitchens, in the wake of the initial fatwa, eloquently explained the stakes. The affair drew a line between “everything I hated versus everything I loved,” he wrote. “In the hate column: dictatorship, religion, stupidity, demagogy, censorship, bullying and intimidation. In the love column: literature, irony, humor, the individual and the defense of free expression.” His words apply to this book.

Many questions are left at the close of “Knife.” It is uncertain if Rushdie will lose the sight in his remaining eye because of macular degeneration. It is unclear where Rushdie and Griffiths will choose to live. But the mood of this book is suggested by this line about going out to a restaurant for the first time since the attack: “After the angel of death, the angel of life.”

The New York Times News Service