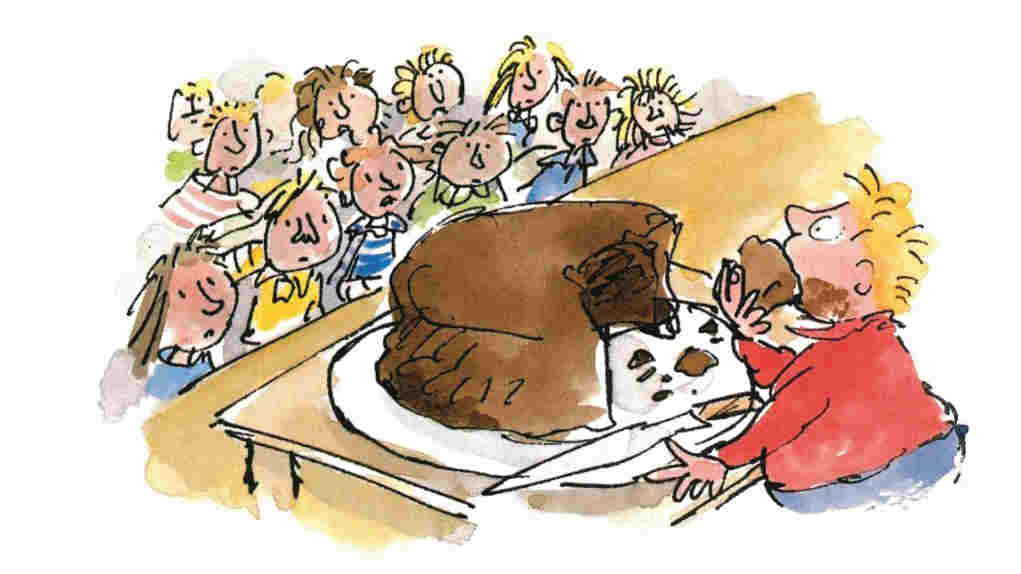

Birthdays are usually considered fitting occasions for cake, which means that it would be apt to consume a slice — or, perhaps, all — of the legendarily decadent chocolate cake from Matilda on September 13; after all, it would mark Roald Dahl’s 104th birth anniversary. In fact, in many ways, that cake and the events in the book that surrounded it served as a microcosm for the complex and fascinating ways in which Dahl understood and wrote about food — for Bruce Bogtrotter’s chocolate cake was never meant to be an appealing dessert. If anything, we are meant to find the idea of a child being forced to eat an entire eighteen-inch cake at one go wholly nauseating.

Indeed, while Dahl’s culinary descriptions bear testimony to his imagination — think of his bubbling chocolate waterfalls and his swirling sugar capriccios — even his most fanciful confections are invariably accompanied by torture and suffering. Augustus Gloop’s gluttony in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory — he dips into the forbidden chocolate river — lands him in the fudge boiler; Bogtrotter manages to finish the cake that Headmistress Trunchbull forces him to eat, but he does so within an inch of his life.

This diabolical power in food is present everywhere in his writing: in Wonka’s chocolate Wonderland where disrespecting the food leads to various kinds of bodily torment; in the rolling peach that kills Spiker and Sponge, James’s cruel aunts; and even in Dahl’s gripping short story for adults, “Taste”, in which a dinner party host loses a high-stakes wine bet to his guest. Dahl lures his readers with his food, and then demonstrates the consequences — ridicule, loss of control, and even death — if they yield.

He is even in his element when writing about bad food. Centipede from James and the Giant Peach eats “hot noodles made from poodles on a slice of garden hose — and a rather smelly jelly made of armadillo’s toes”. Moreover, Roald Dahl’s Revolting Recipes tells us how to make everything from mudburgers to “mosquitoes’ toes and wampfish roes most delicately fried”. Could there have been a more stark insight into the power of human greed to reduce us to mere creatures of instinct? And while the way in which Dahl writes about obesity and, especially, overweight children, is often deeply uncomfortable, there lurks underneath it an understanding that food can wield a chilling power.

However, Bogtrotter’s success in subverting Dahl’s own trope of punishment following gluttony is, perhaps, among the author’s greatest literary achievements. Trunchbull’s attempt to torture and humiliate the child by forcing him to eat, in front of an entire assembly, a huge cake that three adults might have struggled to finish is painful to read. The 250 children watching were convinced that Bogtrotter would “surrender and beg for mercy and then they would have watched the triumphant Trunchbull forcing more and still more cake into the mouth of the gasping boy”.

The boy, however, finished the cake, and in making him do so, Dahl not only masterfully depicts the disturbing masochism in eating to the point of suffering, but also the power in turning another’s attempt to hurt you into a shield for yourself. He ensured that his readers encountered, at every turn, the wondrous and macabre ability of food to give great pleasure and intense pain. The clues are everywhere, but the message is the same: there is sorcery in food — it is glorious, alchemical, savage and, often, impossible to control.