Book: Voices of Dissent: An Essay

Author: Romila Thapar

Publisher: Seagull

Price: Rs 499

A historian is many things. She is a chronicler of the past. She is an interpreter of the present. She is even a foreteller of the future — although thankfully, on rare occasions. But above all, the role that she is most expected to assume from time to time is that of a conscience-keeper. It is the historian who announces the birth of every nation, holds its hand during its infancy, provides it with ideological nourishment and a moral fabric, and sings it the lullaby of its predestination. If the historian is unconscientious, the nation will grow rogue and cause havoc to the world. Sadly, we are living in a perilous time when dishonest historians can do more harm than corrupt politicians.

Whether we agree with her arguments or not, Romila Thapar is one of the most cherished conscience-keepers of our time. Her latest in a long line of influential works is a book-length essay titled Voices of Dissent — a slim but ambitious overture that makes us reconsider some of the categories and paradigms that populate our quest for a collective past and upsets the ready-made narrative of progression once so generously gifted to us by James Mill when he published his six volumes of The History of British India. The chronological classification suggested by Mill, starting with a glorious but unworldly Hindu India followed by a vandalizing Muslim India and saved by a civilizing British India, was almost uncritically embraced by the first of our nationalist leaders and, subsequently, with little modifications, was made part of our school history syllabi. The biggest achievement of a work like Voices of Dissent is that it tries to engage with those of us who were trained in this legacy of unsuspecting absorption of half-informed speculations (Mill wrote his six volumes without knowing a single Indian language and quite proudly so) but remain open-minded to the possibilities of critical thinking.

Written in her usual lucid prose, the essay explores an Indian past when dissent against the established norms defined the contours of public life. Although the theme is not entirely absent in writings on India — Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya and Amartya Sen, among many others, come to mind — it is the environment of growing polarization and upheavals that calls for revisiting some of the past arguments and redrawing continuities, which may have shaped the present that we are sharing. In order to think through these continuities, Thapar uses a broad definition of dissent — “the disagreement that a person or persons may have with others, or, more publicly, with some of the institutions that govern their patterns of life.”

Voices of Dissent: An Essay Author by Romila Thapar, Seagull, Rs 499 Amazon

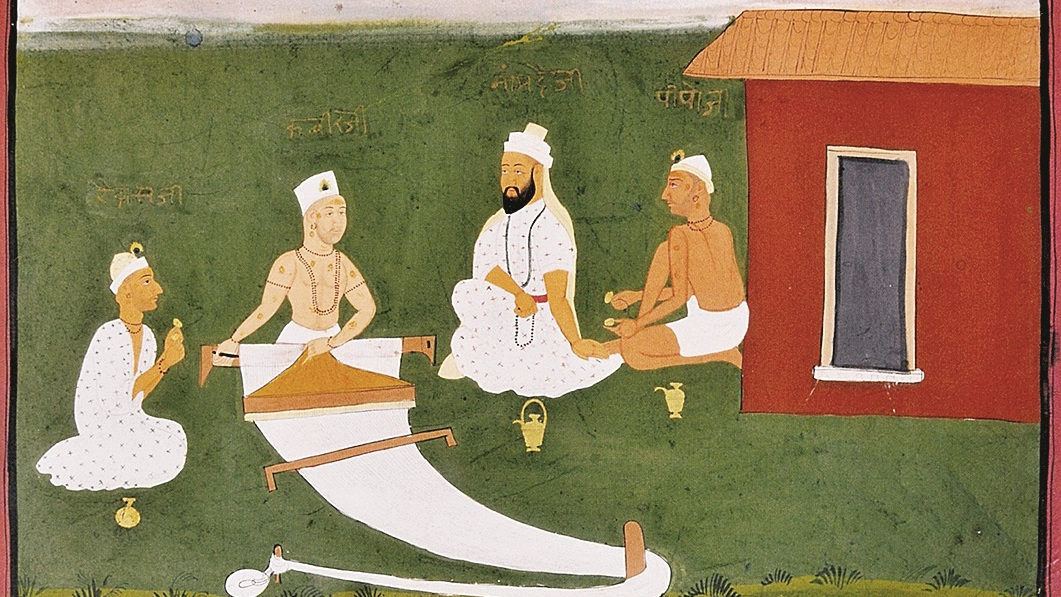

The continuity of dissent, therefore, presupposes the continuity of some of these practices and institutions over a long period of time. As evinced by the recent trends of political mobilization, religion is most definitely a domain where one observes the continued coincidence of institutionalization and dissent. It is also where we witness othering of a disproportionate measure — identifying people and practices as foreign, unacceptable, illegitimate, disturbing, and so on — and creation of a self on the basis of these acts of estrangement. In the essay, the Dasi-putra Brahmana, the Shramanas and the Bhakti sant and the Sufi pir cut such important figures of othering and dissent in pre-colonial India who challenged the hegemonic value systems and transformed the idioms of public discourse.

In Thapar’s account, the disagreements between the religious selves and the dissenting others do not necessarily lead to absolute negation of the dominant religion, namely Hinduism. More often than not, these dissenting voices were formalized themselves and led to the reformulation of the core values of the dominant religion and restructuring of the societies that hosted it, thus making it more “flexible” and giving a “greater verve than the rather confined form in which it is often projected”. What is interesting to note here is the dynamic concept of a public, which evolves out of the participation of common people in these processes of formalization. Although a familiar point but still worth recounting, the paradox of colonial modernity lay in its attempts to ascribe a monolithic structure to these complex pre-colonial practices and, thereby, trying to create a public who would be oblivious of this dynamic, continuous history of dissent.

In the latter half of the essay, Thapar examines Gandhi’s satyagraha, which identified this paradox and tried to reinvigorate a public memory of dissent by channelling a continuity with older symbolisms and idioms of socialization. In her opinion, the voices of dissent that we are hearing today are carrying with them the traces of the same continuity — something that the current proponents of religious nationalism could never anticipate, as their version of religion itself is born out of imagining a different continuity projected by colonialism. It may be pointed out that the break that she proposes between the two continuities is not as clean as it seems, especially when the definitions of the public, people and popular are going through massive rethinking in the light of the rise of right-wing politics all over the world. The essay, even with some of these questions unattended, is a timely reminder for us to raise our own dissenting voices.