Book: Tom Stoppard: A Life

Author: Hermione Lee,

Publisher, price: Faber & Faber, Rs 2,250

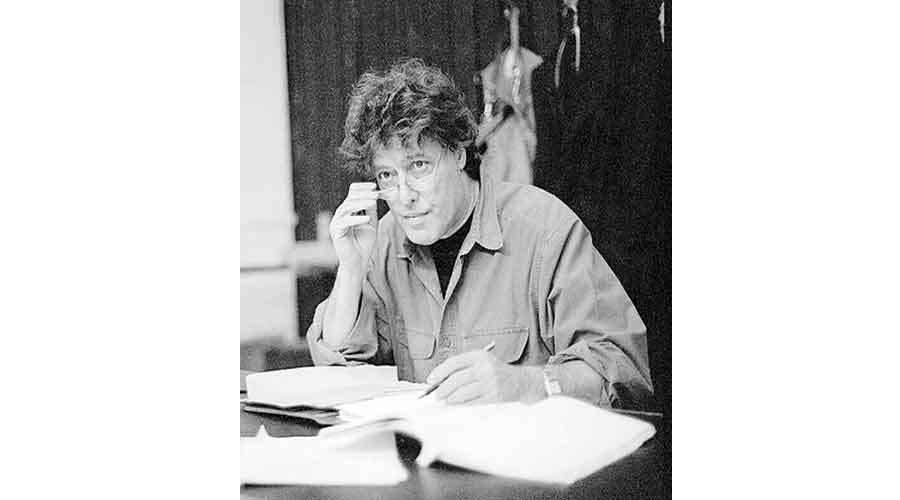

Tom Stoppard recently remembered his childhood in India quite fondly at the Jaipur Literature Festival. Perhaps he was recalling the Kanchenjungha that he saw as a schoolboy at Mount Hermon’s in Darjeeling as he walked all the way to the Bata shop where his mother worked, or maybe to the Mall where he and his mum planned to open their own bookstore to rival the venerable Oxford Book & Stationery Co. Stoppard was born Tomás Straussler in Ziln, Czechoslovakia, where the Batas had their factory; Hitler’s anti-semitism and occupation forces meant that the Strausslers had to flee their home for distant Singapore. Having lost his father in the wartime fracas (the elder Straussler died in a ship that was sunk by the Japanese), Tomás and his mother ended up in India. His mother remarried and his stepfather took the family to Nottingham and Tomás (called Tom from now on) had many exotic stories to tell his schoolmates in Derbyshire. The penchant for stories remained and so did his voracious appetite for reading. Hermione Lee’s biography reads like an unputdownable bildungsroman as she leads her readers into the fantastic reality of Stoppardia.

After leading us into the world of Stoppard’s life as a journalist and then an aspiring playwright (sometimes one who would try too hard as his friends, the authors B.S. Johnson and Zulfikar Ghosh, remarked), Lee also engages with his plays as a critic as well as his biographer. Noting his admiration for Peter O’Toole, whose Hamlet he enjoyed, she addresses his interest in Shakespeare. It was this interest that led to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead and other plays such as Dogg’s Hamlet, Cahoot’s Macbeth and, of course, the screenplay of Shakespeare in Love. Indeed, the love for Shakespeare would be a constant theme in Stoppard as would the impossibility of knowing something for certain. According to Lee, Stoppard liked jokes “which worked so that ‘you think you’ve had it, and then you haven’t...’” His plays, with their acknowledgment of the influence of Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter, still leave their audiences befuddled when they seek the meaning. Just as Lucky, in Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, announces to the world with seeming gravitas, “quaquaqua” or “acacacacademy of anthropopopometry”, with its scatological connections and makes fun of philosophical claims to truth, Stoppard’s characters do the same.

Tom Stoppard: A Life by Hermione Lee, Faber & Faber, Rs 2,250 Amazon

One of his favourite anecdotes is about two men driving along in a car who see a man in pyjamas with his chin covered in shaving foam carrying something like a football under his arm. They struggle to make out whether it is a tortoise or a peacock. As Lee describes it, “They never quite understand what it is they’ve seen. They probably wouldn’t even agree on what it was. The writer […] wants to write about the uncertainty of the witnesses. He is in the position of the man who says: ‘I don’t know!’” It is in this spirit that the documentary on him, called Tom Stoppard Doesn’t Know, has him saying, “I don’t know”, to serious political questions on the Vietnam War or British foreign policy in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Stoppard puts two characters on stage as two representations of himself where they argue for and against theatre as social responsibility. Responding to the serious Stoppard’s example of Bertolt Brecht as the ideal playwright, the frivolous Stoppard retorts: “Personally I’d rather have written Winnie-the-Pooh than the Collected Works of Brecht.” Lee notes that the documentary made quite an impression on viewers.

Lee, however, shows how Stoppard did approach Brecht’s work sensitively, especially when writing Galileo where he engages seriously with Brecht’s play, The Life of Galileo. She also probes deep into the emotions that drive Stoppard’s works and her literary-critical readings of his works supplement the biographical details. Those not as familiar with Stoppard’s oeuvre will get a very clear idea about his versatility, whether it be his Cold War play, Hapgood, or the screenplay for Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Sean Connery, who starred as Indiana Jones’s father, Henry Jones, had an unpleasant run-in with Stoppard over the shooting of the latter’s film adaptation of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead; other than that incident, Stoppard seems to have acquired many celebrity friends. With Felicity Kendal, he had a relationship that was productive for his writing; he wrote many screenplays for Steven Spielberg, often without appearing in the credits; and he was also close with musicians such as Mick Jagger. Lee provides a rounded, but mostly positive, account of Stoppard’s life and work. She points out how detractors have often said, “It’s all very clever, but ...” in response to Stoppard’s plays. Instead, she asks what the legacy of Stoppard is today, when he is such a much-anthologized author and finds his place in almost every English Literature course the world over. According to a commentator, Lee feels that “[i]t’s hard to know how literary history will treat Stoppard”. She concludes that “‘people feel’ he ‘has made a difference to our culture’, but it’s not easy to say what that difference might be” since the lingering questions about the depth and influence of his works will keep rearing their heads from time to time. She says that it will be forever difficult to pin down the real Stoppard and that he ‘will live on in his work: you will find him there, as he has always wanted you to. Once he vanishes, he becomes his admirers.’ Fitting praise, indeed, for the playwright who answers with an “I don’t know” as the serious Stoppard sits face-to-face with the frivolous Stoppard.