Book: The World of India’s First Archaeologist: Letters from Alexander Cunningham

Author: J.D.M. Beglar

Editor: Upinder Singh

Publisher: Oxford

Price: Rs 1,995

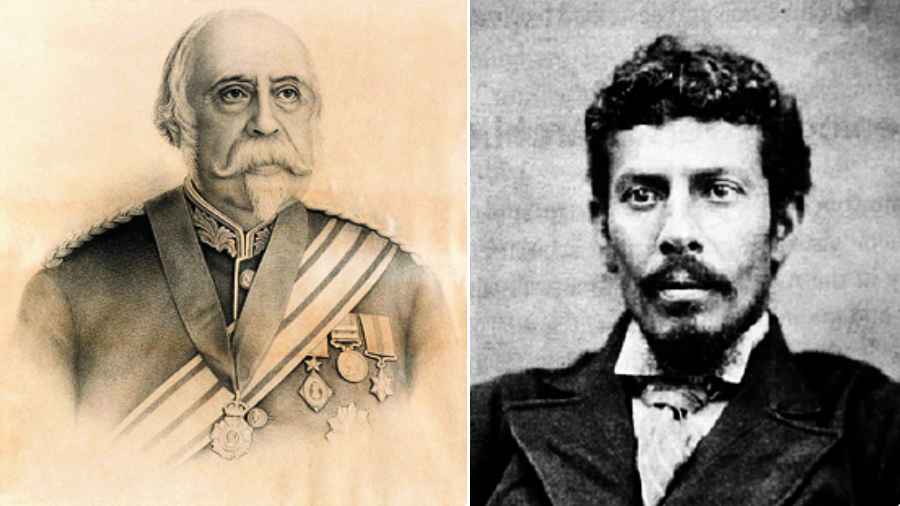

Not many readers may know that the display in the Bharhut Gallery of the Indian Museum, Calcutta, a favourite selfie spot for young couples today, had been meticulously conceptualized by Alexander Cunningham, the first Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India, in the late 1870s. Neither that Cunningham had deputed one of his Archaeological Assistants, J.D.M. Beglar, an Armenian from the Dutch settlement of Chinsurah, north of Calcutta, to supervise this arrangement in the museum. Also, perhaps, not widely known is the fact that much to Cunningham’s consternation, within two to three years of their installation, the Bharhut sculptures, one of the finest specimens of early Buddhist narrative art dating to 2nd-1st centuries BCE, had begun to flake off because of Bengal’s notorious damp. Such exciting nuggets of information can be found in this volume edited by Upinder Singh.

A collection of 192 letters written by Cunningham to Beglar in the 1870s and the 1880s, framed by an exhaustive introduction of almost 80 pages, the book brings to light little-known dimensions of Cunningham’s archaeological endeavours and the early history of institutional archaeology in India. This is quite an achievement since Cunningham’s modus operandi is well-known in scholarly circles through his prolific writings, most notably the 23 annual reports of the Archaeological Survey of India, minutely documenting archaeological sites that he had toured all over the subcontinent (except southern India) between 1862-63 and 1887. For instance, to go back to Bharhut, the preface in Cunningham’s The Stupa of Bharhut (1879) provides an excellent overview of Cunningham’s handling of the excavated antiquities from this early Buddhist stupa site in the princely state of Nagod in central India. Moreover, Cunningham’s pioneering role in laying the foundations of Indian archaeology has been critically examined by scholars such as Abu Imam, Dilip K. Chakrabarti and Upinder Singh herself.

The World of India’s First Archaeologist distinguishes itself on the basis of its hitherto unpublished epistolary material. The letters bring to life a work-obsessed Cunningham writing to his zealous assistant-turned-affectionate friend about diverse matters connected to the incipient field of Indian archaeology as they were unfolding. As the editor puts it succinctly, “They provide direct access to first impressions of sites, the ruminations over their import, the breakthroughs.” One such major archaeological breakthrough of the early 1880s was Beglar’s retrieval of a miniature stone model of the Mahabodhi temple from Bodhgaya in eastern India, when he was working on the repair of this dilapidated structural temple commemorating the Buddha’s enlightenment. Beglar went on to remodel the temple on the basis of this artefact, a move which created a huge controversy between archaeologists and architectural scholars. The letters demonstrate not only Cunningham’s unstinted support to the restoration project of his former aide (who was then working for the Government of Bengal having left the Archaeological Survey of India) but a deep investment in Beglar’s work at Bodhgaya that ranged from guiding him on the conservation of the temple, facilitating the translation of Chinese inscriptions he had discovered, getting a silver cast of the temple model made in Calcutta to even contributing financially. Cunningham was very familiar with Bodhgaya, having explored the site periodically from the 1860s onwards, and his research culminated with the publication of his monograph, Mahabodhi, in 1892. It is a surprising revelation from the letters that Cunningham had originally planned to collaborate with Beglar in producing a comprehensive volume on Bodhgaya. Why that joint publication never came through remains a mystery, just the way it remains enigmatic why Cunningham never wrote about the two Tibetan inscriptions from Bodhgaya, which remained hidden among the Cunningham papers in the British Museum until their publication in 2013.

Cunningham and Beglar worked together officially for almost a decade following the establishment of the Archaeological Survey of India in 1871, travelling extensively and publishing the reports of their surveys regularly. Reading about the enormous challenges that they had to overcome, from budgetary constraints, niggling ill health to the unpredictability of various modes of transport, makes their accomplishments all the more impressive. Like the two archaeologists, the letters connected to them have also covered a long journey, from evidently being held by Beglar until the late 1880s at least to making it to the collection of the Victoria Memorial Hall, Calcutta, around 2005. Perhaps, the editor might have considered discussing a bit about the letters’ provenance and the issue of their access in the current repository.

Providing a much-needed visual context to the letters are a set of 20-odd photographs recording buildings in various places where Cunningham and Beglar had stayed and worked, their gravestones in London and Chinsurah, respectively, and some of the leading figures of early Indian archaeology. The inclusion of photographs is apposite given that Beglar’s major contribution lies in his photographic documentation of archaeological monuments.