Book: The Fear of the Visual? Photography, Anthropology, and Anxieties of Seeing

Author: Sasanka Perera

Publisher: Orient BlackSwan

Price: Rs 850

Does anthropology suffer from a fear of the visual? While exploring this question, Sasanka Perera’s book takes upon itself the herculean task of historically analysing the intellectual rupture between the practice of anthropology and that of photography. For disciplines that have always prioritized ‘seeing’, the author finds it paradoxical that images are eclipsed by the written word — hence the use of the phrase, ‘anxieties of seeing’, in the title of the book. Perera closes his argument with the contention that the current manifestation of this (in)articulated fear needs to be situated within the post ‘writing culture’ theoretical and methodological paradigm. It created a ‘written’ word-centrism, thereby hierarchically positioning one kind of seeing (through participant observation/fieldwork/ethnography followed by writing) above another (captured through a camera). Consequently, there is a persistent failure to treat photographs as texts, to be contextualized, theorized, interpreted and represented. Drawing on an impressive number of scholars in the field, Perera addresses this continual lack and urges us to look at the visual not as a residue but as an integral part of what an anthropologist might see, comprehend, interpret and represent and at photography as an acceptable methodological device that can help the practitioners of sociology and social anthropology to find new ‘ways of seeing’ and a new voice for themselves.

Perera’s book can be set apart from many others on the subject because of its entrée into the debate. It is indeed refreshing to read an academic account, which places equal emphasis on autobiographical underpinnings as on academic frames of references and their constraints. Perera uses his personal recollections to build an academic narrative of themes, arguments and conclusions, giving us a book that privileges ongoing, hence incomplete, negotiations among the personal, the professional and the political on the one hand and the wider theoretical, methodological and disciplinary concerns on the other. His location in the global South (Sri Lanka and India) adds a fascinating layer to this negotiation and its articulation thereafter.

The book, which is embedded in scholarly rigour as is evident in its exhaustive bibliography, may have much to offer to the uninitiated to this debate. Those who have been working with the themes and the debates that the book engages with may find the South Asian empirical content to be a welcome addition to the conventional Euro-American repertoire of theories and methodologies. It adds an important dimension to the fraught relationship between the image and the word. Many scholars, notably Christopher Pinney, have shown that the image has a more powerful role to play than the written word in the South Asian context. This is largely because of the rich repository of oral narratives, folklores and visual imagery within the region. Hence, anthropological and sociological research in the region can benefit much from redefining ‘seeing’ through the practice of photography.

The Fear of the Visual? Photography, Anthropology, and Anxieties of Seeing by Sasanka Perera, Orient BlackSwan, Rs 850 Amazon

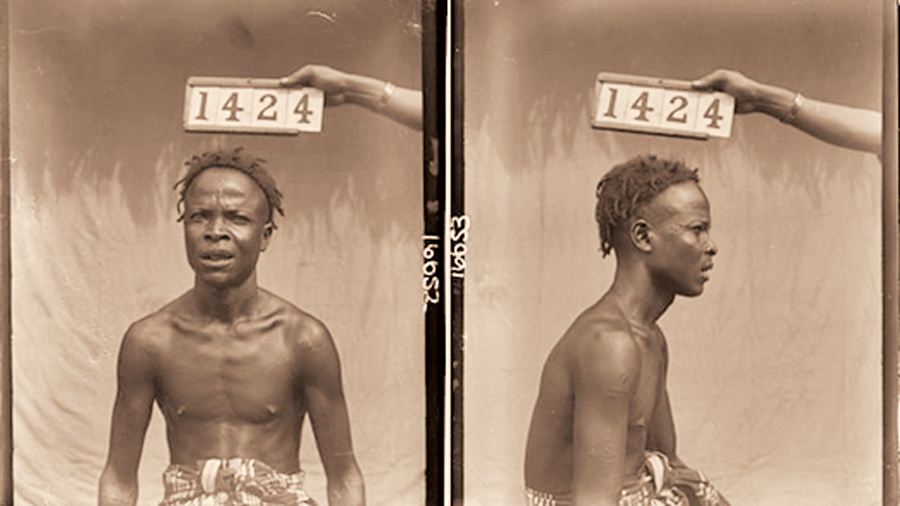

The book is divided into nine chapters, each of which begins with a quote followed by a personal narrative juxtaposed with images from Perera’s personal collection, only to usher his reader into an academic engagement with an overarching theme. In the introduction, he underscores the ‘incompleteness’ of an image and its interpretation, the role played by personal and collective memory, and the narrative possibilities of photography to explore people’s social and cultural worlds — past and present. Chapter two and three revisit the synchronous histories of colonialism and anthropology and their intersection with the practice of photography in the South Asian context, attempting to reveal and redraw the discursive trope in which the region has been caught for long. Chapter four and five mark a shift in the narrative by examining the fragmented history and the politics of the practice of photography by focusing on the construction of a (public) ‘self’ aided through technology. Located within contemporary times, these two chapters offer new sites (selfies and wedding pictures) through which photography can be analysed. Chapter six adds to the narrative built in chapter three, examining the factors underlying the emergence of two sub-disciplines — visual anthropology and visual sociology — and their implications. Perera illustrates how, despite creating a broader composite area of work and exerting influence through method and approach, they are still peripheral to the disciplinary contours of mainstream sociology and social anthropology. The following chapter explores the ethical question related to issues of informed consent, privacy, copyright, representation and circulation, anonymity and manipulation in visual research. Even though the chapter may not give a set of guidelines for how it should be done, it does open up an arena for future discussion. Chapter eight argues for a synchronic analysis of the existing practice of photography (“fleeting, casual and unthinking” as Perera calls it) by engaging with contemporary structures of digital technology and discursive frameworks of fragmented selves. The concluding chapter brings the narrative to a full circle by raising similar scepticism and anxieties about the practice of anthropology and sociology, which are often raised within these disciplines for the practice of photography. In the end, Perera asserts that unless our attitude towards photography undergoes a metamorphosis, we might not be able to placate some of our anxieties and utilize the potential that it has to offer.

The Fear of the Visual? is thus a conversation at multiple levels: among sociology, anthropology and photography; between past and present; between European-North American and South Asian systems of thought but, most importantly, between one kind of seeing and another. It is a conversation that is continual, fragmented, has multiple trajectories and, hence, should be contextualized in and explored at multiple sites and temporalities.